Born in Jamaica in 1925, Baker came to Britain in 1944, aged 19. Baker joined the RAF as a policeman, lying he said he was 21, because of his eagerness to fight against Hitler.

Baker found ordinary Britons welcoming to those who were fighting with them, his first experience of racism was to be in a pub in Gloucester where American soldiers refused to drink alongside black customers. Baker, who thought of himself at British reacted angrily. His disgust at racism would lead him to heckle Oswald Mosley as he espoused fascism.

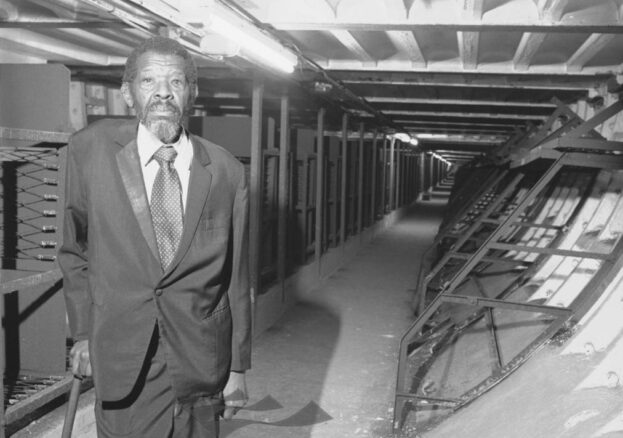

Baker had joined the RAF to fight fascism and would continue to fight fascism and racism once the war was over. After being demobilised in 1948 he would fight against British government plans to repatriate Caribbean servicemen after the Second World War, after the Empire Windrush arrived in 1948, beginning the immigration to Britain of thousands of men and women from the Caribbean, many faced immediate discrimination in their attempts to find shelter and Baker persuaded the government to open Clapham South’s air raid shelter to provide temporary accommodation on occasion Baker would stay in the shelter himself. Looking for a longer-term solution Baker and others sought to establish black communities in London.

Baker would become known as the `man who discovered Brixton`, an area where people from the Caribbean were able to find jobs and homes. Baker would continue to fight against racism both politically and physically. In race riots in 1958 Baker and his friends using their own military experience met hundreds of white rioters, ultimately chasing the rioters away. Baker would go on to found the United Africa-Asia league to fight discrimination and would make regular speeches against racism at Hyde Park’s Speakers Corner

Baker lived the remainder of his life in Notting Hill; he died in 1996. His funeral was held in Kensal Green Cemetery; where he was remembered as a respected and important member of the community.

As the nation’s largest Armed Forces charity, the Royal British Legion (RBL) is dedicated to ensuring that all those who served and sacrificed, and who continue to do so, in defence of our freedoms and way of life, from both Britain and the Commonwealth, are remembered.

In our acts of Remembrance, the RBL remembers,

- The sacrifice of the Armed Forces community from Britain and the Commonwealth.

- Pays tribute to the special contribution of families and of the emergency services.

- Acknowledges the innocent civilians who have lost their lives in conflict and acts of terrorism.

The story of Black British and Black African and Caribbean service and sacrifice is one that we are keen to share, a story of men and women who have done so much in defence of Britain and in protecting all our citizens. A story that is replete with stories of bravery and courage, as epitomised by Victoria Cross winner Johnson Beharry.

Therefore, to mark 100 years since Britain’s current Remembrance traditions first came together, the RBL has bought together over 100 stories of British and Commonwealth African and Caribbean service and sacrifice. The stories range from the First World War to the present day and are of servicemen and women from across Britain, Africa and the Caribbean, representing both the armed forces and emergency services.

Therefore, to mark 100 years since Britain’s current Remembrance traditions first came together, the RBL has bought together over 100 stories of British and Commonwealth African and Caribbean service and sacrifice. The stories range from the First World War to the present day and are of servicemen and women from across Britain, Africa and the Caribbean, representing both the armed forces and emergency services.

The RBL wishes to offer special thanks to Stephen Bourne for his help in putting these stories together. Stephen Bourne has been writing Black British history books for thirty years. For Aunt Esther’s Story (1991) he received the Raymond Williams Prize for Community Publishing. His best-known books are Black Poppies (2019) and Under Fire (2020). His latest book Deep Are the Roots – Trailblazers Who Changed Black British Theatre was recently published by The History Press. For further information about Stephen and his books, go to his website www.stephenbourne.co.uk