There were sizable Black communities in Cardiff, Liverpool and South Shields but it is likely that for most growing up was a question of struggling to assimilate to life in England as unobtrusively as possible.

After the 1950s, however, growing up under the protection of a larger migrant community began to present opportunities. Over the second half of the century, migrant children began to be the standard bearers of a new identity, which emerged out of the meeting between the heritage of their parentage and the nature of their new environment.

Early Days

Before the 20th century, most Caribbean migrants arriving on British shores were, with some notable exceptions, already adults, or at least young adults. Their children, born in Britain and frequently of mixed parentage, were assimilated with varying degrees of success. However, a number of surveys and reports from the early part of the 20th century tell us of the difficulties that ‘coloured youth’ faced in obtaining any kind of employment.

In 1936, the League of Coloured People appealed for ‘assistance in placing the coloured youth in Cardiff who are growing up without opportunities for work’ in it’s newsletter. ‘The average employer,’ it continued, ‘would much sooner have an alien employee than a coloured British one. So of course it is with hotels and landladies offering appointments.’

Again in 1939, the LCP was reporting discrimination against Black children who were being evacuated from British cities to the country during the early years of the war: ‘Among a large party of children which came to our district were two little coloured boys,’ reported the League of Coloured People’s Newsletter. ‘Nobody wanted them. House after house refused to have them. Finally a very poor old lady of seventy years volunteered to care for them. As she folded their clothes, she discovered two letters addressed to the person who adopted them. Each letter contained a five pound note.’

The rejection faced by these children echoes the conditions faced by most young mixed race children during the period.

Post War Growing Up

For Caribbean children who arrived in the wave of Post-War migration, Britain presented huge differences to their previous lives. Growing up in the Caribbean, an area of the world characterised by poverty and high unemployment, could undoubtedly be hard, but it had certain positive and agreeable features.

Within the small populations of the West Indian islands, the extended family provided a safety net, which offered a high level of security. The island communities were a setting which provided a considerable amount of social ease. With the beaches, fields and rivers close to the villages and small towns, children had enormous amounts of space in which to play, and they felt safe and at liberty there. Most people had confidence in the educational system and the prospects it offered, and children treated teachers with as much respect as their parents.

In comparison, most migrant children growing up in Britain found themselves doing so against a background of cramped and tightly contained urban living conditions, and surrounded by dangerous streets occupied by what often appeared to be a hostile and abusive host community. At school migrant children felt pressured, discriminated against and anxious about their prospects.

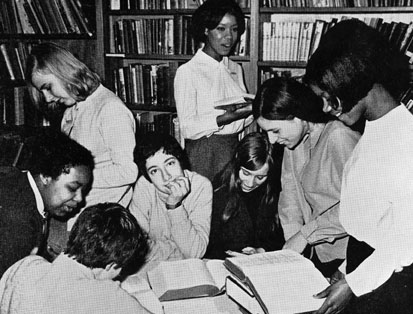

Schooldays

Young Caribbean migrants growing up in England during and immediately after the Second World War faced a number of prejudices within theeducation system , but there were no alternatives or factors to counterbalance the problems they faced. Unlike the Jewish community, there was no network of charitable resources or sympathisers within the broader society who could establish exclusive schools or clubs. Nor could children retreat to a completely separate cultural sphere. For instance, they couldn’t take psychic refuge in speaking in their ‘mother tongue’; English was their native language, but they used unfamiliar accents and dialects. All too often teachers assumed this to be ignorance and poor performance.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, a disproportionate number of Caribbean migrant children were classified as ‘educationally subnormal’ and placed in special schools and units. It was easy to tell from the official statistics by the early 1970s that young migrants were disadvantaged within the education system. By the end of the 1980s, the chances of white school leavers finding employment were four times better than those of Black pupils. Read this 1973 education file on the particular problems of Caribbean children attending English schools.

The most important work which The League has recently undertaken for the benefit of the coloured workers of this country, concerns the future of the children. These children seem to suffer no outstanding difficulties as long as they are at school, but on leaving school, all avenues seem to be closed to them. Taken from The League of Coloured People’s 7th Annual Report, 1938. Read the full 7th annual report.

At the same time the migrants’ perception of police harassment and public hostility, and the dominance of ‘rebel music’ in their social life, gave young migrants an identity which appeared angry and anti-authoritarian. Ironically, while white youth culture was eager to adopt the style, the language and the music of migrant youths, British society as a whole used these characteristics as justification for discrimination.

Areas of Excellence

There was a significant number of migrants who did not fit this mould. They often came from small communities living in the outer suburbs of Britain’s industrial centres, and were relatively isolated from the trends within the larger urban migrant communities.

These young migrants found themselves in a very small minority – one of only three or four Black children in a school. The only choice available was rapid and successful assimilation. Gary Younge, a writer who grew up in Stevenage, draws interesting comparisons between his experience and those of young migrants brought up in inner city areas.

For most of the second half of the 20th century, sport and music were among the few areas which offered young people of Caribbean backgrounds opportunities for successful achievement, whether or not they had been born in Britain. This was partly because success in these spheres did not challenge established prejudices. After all, the most successful Caribbeans in the stifling pre-War atmosphere had been musicians and sportsmen, like the cricketer Sir Learie Constantine who had been revered by the English public. For a time commentators would stereotype Black sportspeople as ‘natural’ athletes.

Young Caribbean migrants took advantage of the fact that sport was the one arena where it was possible to compete on equal terms and, from the 1950s onwards, many played a prominent part in Britain’s sporting life.

Music, on the other hand, presented different opportunities but also problems. In the days before reggae gained general acceptance, young migrants forged their music into a tool of self-expression and used it as a career opportunity. They created their own market for the music which, in turn, gave them a platform from which they influenced British youth culture.

In the process, the music created its own market: clubs, small recording companies and, notably, DJs. It was this music culture which helped to create a new, cohesive identity among young migrants, and one which everyone began to recognise as ‘Black British’. Jazzy B, for instance, one of the most prominent of recent Black British musicians, went to school in Islington, and spent his spare time learning to be a DJ and creating his own music to give voice to an emerging Black British culture.

By the 1980s, growing up in this country had ceased to be a tightrope walk between the Caribbean and Britain. Instead, young people with a Caribbean background were forging their own version of what it meant to be British.

Further Reading

The Fire People – A collection of Contemporary Black British Poets, edited by Lemn Sissay, 1998, Payback Press, an imprint of Canongate Books