A spring afternoon in 1963. Eighteen-year-old Guy Bailey arrived on time for his job interview. Bailey was well qualified for the post, but he would not be taken on. Because he was black.

He strolled up to the front desk. He told the receptionist why he was there. She looked up at him. “I don’t think so,” she said.

Bailey thought she must be mistaken. “The name is Mr Bailey,” he told her.

The receptionist stood and went to the manager’s office. Bailey heard her call through his door: “Your two o’clock appointment is here, and he’s black.”

The manager shouted back from inside his room: “Tell him the vacancies are full.”

Bailey protested. There was an advert for applicants in the local paper only the day before. Just an hour ago, his friend had rung the same office and been told there were plenty of jobs.

“There’s no point having an interview,” said the manager, still in his office, refusing to come out and meet Bailey’s eyes. “We don’t employ black people.”

Encounters of this sort were then familiar in many parts of the world. The newspapers were full of stories about the struggle against segregation in the deep south of the US and the fight against apartheid in South Africa.

But this wasn’t Alabama or Mississippi. This wasn’t Johannesburg or Pretoria.

This was Bristol, in England, in 1963.

The manager who refused Bailey a job was acting entirely within his rights.

Half a century ago it was legal in the UK to discriminate against someone because of the colour of their skin.

At the state-owned Bristol Omnibus Company, run by the local council, the “colour bar” was an open secret. Despite the presence of an established Caribbean community in the city, no non-white driver or conductor had ever been employed on the network.

The company’s management acted with the connivance of the local branch of the trade union that represented bus crews. These were the days when workplace unrest was common, but on this issue both sides of the industrial divide stood together against integration.

But Bailey’s unsuccessful interview marked a turning point. Members of the local black community, supported by many of their white neighbours, led a boycott of the network in protest.

Quite consciously, the campaigners imitated the non-violent anti-racist crusade of Martin Luther King and other American advocates of racial tolerance.

The Bristol boycott was to prove a watershed moment. The campaigners maintain that their efforts directly led to the UK’s first ever laws against race-based discrimination.

Today, outside Bristol, the story of the bus boycott is barely known. But to those who led it, this was the UK’s own version of the civil rights movement that shook the American south.

In 1960, Bristol’s Caribbean community numbered about 3,000. Most had arrived from the Caribbean after World War II. The 1948 British Nationality Act meant they had British passports with full rights of entry and settlement to the UK.

Many had served Queen and country. Nearly all, like Bailey, had been schooled under the British education system. And at a time of virtually full employment, employers like London Transport and the National Health Service had actively sought their labour.

But the reception they received from their fellow British subjects was frequently less than welcoming.

Bailey recalls his shock, not long after he first came to Bristol in 1961, when he was chased by gangs of Teddy Boys wielding bicycle chains, their blows landing on the back of his head as he ran.

For a young man raised in Jamaica by a fervently monarchist British Army veteran father, this went against everything he had been brought up to expect of the place he knew as the “mother country”.

“Bristol was a very cold city,” recalls Bailey of his early years in the UK, “both in terms of the weather and the people.”

Fearful of physical attacks, the black community was largely confined to the deprived St Paul’s area.

The few boarding houses prepared to rent rooms to non-whites charged a premium. Some others displayed signs in the window reading: “No Irish, no blacks, no dogs.”

“You couldn’t go into pubs in Bristol on your own, not if you were black,” remembers Roy Hackett, who emigrated to the UK in 1952.

“You’d get a hiding. You had to go in two or three at a time. There were shops that wouldn’t serve us. Ninety per cent of us, if we had been able to go back we would have. If I’d had £35, I would have done it.”

Hackett knew from bitter experience that the “colour bar” existed in employment.

When he went for one labouring job, he was told the company did not employ “Africans”. Hackett protested indignantly that he was Jamaican – if he was going to be discriminated against, the least they could do was get his nationality right.

In 1962, his wife Ena applied for a job as a bus conductor. She was turned down despite meeting all the requirements of the post. Everyone assumed her colour was the disqualifying factor.

At the time, there was no Race Relations Act, and employers could not be prosecuted for discriminating on racist grounds. Newcomers from the Caribbean encountered prejudice when applying for work in other towns and cities, too.

But even in the early 1960s, Bristol’s race bar on the buses stood out. Non-white drivers and conductors were a familiar sight across much of the UK.

Just 12 miles away in Bath, black crews were working on buses. London Transport recruitment officers had travelled to Barbados specifically to invite workers to come to the capital.

To the black community, the history of Bristol – a one-time major slave port, which still had multiple streets and landmarks named after the slave trader Edward Colston – loomed large.

Hackett had had enough. Along with several other St Paul’s residents he formed a group called the West Indian Development Council to lobby for rights.

The group was galvanised by the arrival in Bristol in 1962 of a young man called Paul Stephenson. The son of an African father and a white British mother, Stephenson had been brought up in Essex before National Service in the RAF and a social work degree in Birmingham.

Unlike the older immigrants who had served as de facto representatives of black Bristol, Stephenson did not fear rocking the boat and had no interest in effecting gradual change. He was bold, pushy and wanted equality there and then.

Stephenson was employed as a youth officer. But what really motivated him was racial injustice and the inspiration of the US civil rights movement.

In particular, he recalled the year-long bus boycott in the city of Montgomery, Alabama, launched after one African-American woman famously refused to take the seats reserved for black passengers.

“I had seen Rosa Parks – her defiant struggle against sitting at the back of the bus,” he remembers.

Stephenson had an idea.

At first no-one admitted that black people were banned from working on Bristol’s bus crews. Anyone who was even vaguely acquainted with the service, however, was aware that no non-white person would ever be seen behind the wheels of its fleet.

The cover was broken in 1961 when the local newspaper, the Bristol Evening Post, ran a series of articles alleging the

existence of the “colour bar”.

Ian Patey, the general manager of the Bristol Omnibus Company, told the paper that it did employ a few non-whites “in the garage but this was labouring work in which capacity most employers were prepared to accept them”. In other words, he would not tolerate them working as drivers or conductors.

Patey made his position more explicit before a meeting of Bristol’s Joint Transport Committee in March 1962. He told members there was “factual evidence” that the presence of black crews would downgrade the job and drive existing staff away. The committee voted not to overturn his policy.

But it was not only management which took this attitude. According to at least one account, in 1955 the Passenger Group (which represented drivers and conductors) of Bristol’s Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) passed a resolution that black workers should not be employed as bus crews.

The union operated a closed shop on Bristol’s buses – no-one could be employed on the service unless they belonged to and were approved by the TGWU.

Unlike management, however, the TGWU did not acknowledge at the time that discrimination represented branch policy.

Indeed, the union – then the UK’s largest, with more than a million members – was at least in theory committed to anti-racism. Its national leaders spoke out against apartheid in South Africa. In Bristol, hundreds of black employees at the city’s Fry’s chocolate factory belonged to the TGWU. So too – in the days when a union card was often essential to get work – did Bailey, Hackett and Stephenson.

There were even black TGWU members within the Bristol Omnibus Company. At the same time that the Passenger Group voted to exclude black workers, the maintenance section – which represented the garages – appears to have voted to take on non-white members in the garages.

But those who worked for the company were all too aware that black employees were not welcome on board once the buses left the station.

“I knew it was going on,” says Steve Bishop (not his real name), who worked both as a conductor and a driver in Bristol. “It was a colour bar.”

A young man with two small children to support, Bishop kept out of union politics. But he was aware of the mutterings in the canteen and the pubs after work.

If black workers were hired, he recalls, “everyone said there would be overtime cuts if not job losses”.

Bishop didn’t argue with them. He adds: “It wouldn’t stand the light of day now.”

As part of his youth worker duties, Stephenson had been teaching night classes to young people. One of his pupils was Guy Bailey.

Stephenson had decided the time had come to challenge the bus company’s race bar. Bailey, he judged, made an ideal “stalking horse” – well-spoken, educated, a cricket player, churchgoer and former Boy’s Brigade officer – and it would be difficult to justify refusing such an upstanding young gentleman a job.

For his part, Bailey was excited about the prospect of working on the buses. He had a steady job as a dispatch clerk in a garment warehouse, but the vehicles he saw rumbling through Bristol each day offered a more exciting career.

“I thought they were really unusual because I’d never seen them before I came here,” Bailey recalls. “I thought, I’d love to drive one of those things.” Driving sounded like a more exciting career than working behind a desk.

An advert had appeared in the Evening Post asking would-be conductors to call to arrange an interview. Bailey knew that drivers had to serve an apprenticeship collecting tickets before they were allowed behind the wheel. Stephenson saw an opportunity to expose the racist hiring policy.

Fifty years on, the two men’s recollections differ as to just how aware Bailey was of the company’s discriminatory policies. Stephenson insists he warned the younger man not to get his hopes up. Bailey says he had no idea he didn’t stand a chance.

Both agree what happened next, however. One day in April 1963, Stephenson – who spoke with an Essex accent, and would not be identified from the other end of the phone line as black – called the company’s headquarters on Bailey’s behalf.

He said one of his night school pupils was keen to work as a conductor. Stephenson was told to send him along.

For his interview, Bailey wanted to look his best. His fashion role model was Simon Templar, the sharply dressed action hero played by Roger Moore in the TV serial The Saint.

“He used to dress quite nicely, he used to wear a blazer and grey trousers,” smiles Bailey. “So I had shirt and tie, blazer, grey trousers and I thought I was Simon Templar.”

It didn’t do Bailey any good. That night he turned up to his night class and told Stephenson that he had been refused the job because of his colour.

The older man had been expecting this. The campaign he had been planning was about to begin.

“Now was the time to take up the issue and do what Martin Luther King was doing,” he says.

It started with a press conference. The local media were invited to Stephenson’s St Paul’s flat and told what happened to Bailey at the bus company headquarters.

Passionately denouncing the “colour bar”, Stephenson urged a boycott of the service until the policy of discrimination was ended.

“I put the emphasis on the manager of the bus company to take responsibility,” he says.

To illustrate the parallels with the US, local photographers were invited to follow a young black man named Owen Henry on to a Bristol bus. Pointedly, Henry stood at the back.

The stunt caught the imagination of the newspapers. They contacted Patey, who confirmed explicitly once again that black people were not welcome to serve on his fleet.

“We don’t employ a mixed labour force as bus crews because we have found from observing other bus companies that the labour supply gets worse if the labour force is mixed,” Patey told the Evening Post.

In an editorial, the newspaper strongly condemned the policy.

But it did not lay all of the blame on Patey and his management. The TGWU, it alleged, was not doing enough “to get the race virus out of the systems of their ranks and file”.

As the national as well as the local media began to take notice of the boycott, the focus was about to shift towards the drivers and conductors.

The bus crews and their union were caught off-guard by the boycott.

For as long as most of the younger staff could remember, the absence of any black colleagues had been an unmistakable, if rarely acknowledged, fact.

“I never worked on the buses with black guys,” says Bishop, who had previously served quite happily alongside black colleagues in other workplaces. “I was a member of the union but I didn’t give it much thought – I wasn’t directly affected.

“I was always a union man. I remember being of the opinion – well, it’s the union, and they’re of the same mind.”

At first the TGWU’s regional secretary Ron Nethercott – at the time dubbed “the most powerful man in the West Country” by the local media – publicly declared that the crews would have no objection to black labour joining their ranks. He was soon contradicted by drivers and conductors who told the media they would refuse to serve alongside non-whites.

However, Nethercott, now aged 90, insists the bus workers were not motivated by colour prejudice but by a fear that their income would be eroded.

Basic wages on the buses were relatively low by Bristol standards. Before the war they had matched those of skilled workers at the city’s British Aerospace plant, but had since fallen behind.

To match the standards of living of their neighbours, bus crews invariably volunteered for overtime.

According to one ex-conductor, it was common to work from 04:30 or 05:00 each morning until midnight. Most aimed to clock in 100 hours a week, which would raise their take-home pay to £20 – just above the average weekly wage in the early 1960s.

To be guaranteed this much overtime, however, the bus crews’ rotas had to be understaffed.

At the same time, management had raised the prospect of “one-man operated buses” (OMOs), which required only one bus worker on board each vehicle to act both as driver and conductor. As a result, many felt their jobs were precarious.

The busmen’s wages were so low that they depended on overtime to make a living

According to Nethercott, it was the threat of having their incomes diluted by a newly arrived pool of migrant labour that motivated the Passenger Group’s members to uphold the bar, not racial prejudice.

“Wherever they they came from, Europe, China, Alaska, it made no difference,” he says.

“The busmen would have still resented it because they were taking away their overtime. Their wages were so damn low that they depended on overtime to make a living.”

Not everyone agrees that the crews were entirely motivated by economic concerns, however.

Tony Fear began working as a “strapper”, or a new conductor, at the start of 1961 aged 18. Having served in the Territorial Army he had a number of black friends, and was shocked by what he considered outright racism on the part of his new colleagues.

“The worst were the conductresses, I have to say,” Fear recalls. “They were terrible. They’d say a black conductor would eventually become a driver, therefore they’d have to work with a black driver, and the things they could do at the end of the journey, you know? It was terrible. They thought they were wide open to rape. They believed that.”

As for male bus crews, the older staff – men in their 40s and 50s who had typically served alongside Commonwealth regiments in WWII – tended not to have a problem with the prospect of black colleagues, according to Fear. It was their younger counterparts who were more likely to be bigoted.

“Where did that prejudice come from in that generation, people in their 20s and 30s? I was saddened by it,” recalls Fear.

As voices from outside the depot were raised in opposition to discrimination at the company, Fear voiced his support for Bristol’s black community: “I was sympathetic and I wasn’t afraid to say so.” His colleagues listened to him respectfully, but few signalled their agreement.

For all that the union undoubtedly played its part in denying black workers jobs, however, Stephenson believes the ultimate blame for the discriminatory policies lay with the management for having set the terms of debate.

“The ordinary workers took their cue from the Bristol Omnibus Company,” he says.

“The unions were more concerned about their economic situation. They thought the black workers were lower status and would bring about wage decreases – it was economic racism.

“Some of them were racist – they didn’t want to work with black people. But it was the management, it was the city council that was ultimately responsible.”

The boycott quickly gathered pace. Supporters refused to use the buses. Marches were held across the city. Depots were picketed.

Students at Bristol University – particularly those in radical groups like the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination – swelled the ranks of the protests. Around a hundred of them marched on the TGWU’s offices.

High-profile politicians lent their support, too. Bristol South East MP Tony Benn – then known as Anthony Wedgwood Benn – declared he would “stay off the buses, even if I have to find a bike”. Labour leader Harold Wilson, who would be elected prime minister the following year, told an anti-apartheid rally in London he was “glad that so many Bristolians are supporting the [boycott] campaign… we wish them every success”.

Sir Learie Constantine, the celebrated ex-West Indies cricketer who was High Commissioner for Trinidad and Tobago, publicly condemned the bus company. So too did diplomats from Jamaica

The media was lobbied tirelessly by the indefatigable Stephenson. Intrigued by the parallels with the American south, reporters from London headed west and made the comparison, to the embarrassment of Bristol’s civic leaders.

They were not the only ones who found the attention uncomfortable. “I was being bombarded or harassed or being set upon by the media,” says Bailey, who had a less effusive personality than Stephenson.

And yet as Stephenson predicted, Bailey’s quiet dignity made him an ideal figurehead. It wasn’t only outsiders who disapproved of his treatment. Public opinion in Bristol itself shifted in favour of the protesters.

In Montgomery, Alabama, the boycott had succeeded in part because African-Americans formed a large proportion of the bus operators’ customers. In Bristol their numbers were not so large. Instead, the purpose of the British boycott was to generate propaganda – drawing parallels with US segregation and shaming the authorities – while causing as much disruption as possible.

Pickets of bus depots and routes were a key part of the strategy. Hackett organised blockades and sit-down protests at Fishponds Road in the north-east of Bristol to prevent buses getting through to the city centre.

“White women taking their kids to school or going to work would ask us what it was about,” Hackett says. “Later they came and joined us.”

Like King’s campaign, the methods were strictly non-violent. “I said to everyone, not one stick and not one stone.”

In fairness, he says, their opponents responded on the same basis: “They gave us a lot of harsh words but they never harassed us physically.”

By now, it was the bus crews who were bearing the brunt of the pressure.

As the summer wore on, the TGWU in Bristol was increasingly isolated.

Their erstwhile comrades in Bristol’s other unions were becoming hostile.

At a May Day rally organised by Bristol Trades Council, the bus workers were condemned from the platform while TGWU members were heckled and barracked by other unionists for bringing shame on the labour movement.

Passengers, too, were increasingly voicing their disapproval of the bus crews. “In those days the buses were so important that all they’d want to do was see a bus that they could get on,” recalls Fear. “I don’t think they cared who drove it or who conducted it.

“People were saying: ‘If it was a black driver we’d be on time.’ That didn’t help. Or: ‘Oh flipping heck, if you were a black conductor you’d know where I want to get off.’ That caused a lot of bad feeling, it really did.”

Nethercott was feeling embattled. Attacked by his own members for suggesting they would be prepared to work alongside black crews, he engaged in a public war of words with Stephenson which led to the union leader losing a libel action brought by the young activist.

An attempt to broker a compromise, with a black TGWU member signing a statement which called for “sensible and quiet compromise”, came to nothing.

“Everybody was scared of it,” complains Nethercott, still visibly aggrieved 50 years on.

“The great problem around that time was that people lacked courage. They didn’t want to get involved. So it was left to the likes of me.”

It was clear something had to give.

“I think the union realised they were losing the argument,” says Fear.

On 28 August 1963, 250,000 people marched on Washington DC to demand civil rights for African-Americans. At the Lincoln Memorial, Martin Luther King stood before the crowd and delivered his famous “I have a dream” speech.

“From every mountainside,” King declared, “Let freedom ring.”

That same day was a momentous one for Bristol, too. On 28 August, Ian Patey declared a change in policy at the Bristol Omnibus Company. There would now be “complete integration” on the buses, “without regard to race, colour or creed”, Patey added.

The night before, a meeting of 500 TGWU bus workers had voted to agree to “the employment of suitable coloured workers as bus crews”. The boycott had succeeded. The colour bar was dead.

By mid-September Bristol had its first non-white bus conductor. Raghbir Singh, an Indian-born Sikh, had lived in Bristol since 1959. On his first day, he told the Western Daily Press he would wear a blue turban to work because it “goes with my uniform. If I wear a brown suit I have on a brown turban”. Further black and Asian bus crews quickly followed.

Guy Bailey was not among them. The rejection he had experienced, and the campaign that followed him, had put him off the notion of working on the buses.

“I felt unwanted, I felt helpless, I felt the whole world had caved in around me. I didn’t think I would live through it,” he says. “But it was worth it.”

Those black and Asian crews might have expected a hostile reception but, says Tony Fear, the most vociferously bigoted conductors and drivers handed in their notice rather than work with non-whites.

The impact of the boycott’s success was not only felt by those who gained jobs with the Bristol Bus Company. Stephenson believes the Race Relations Acts of 1965 and 1968, which banned discrimination in public places and in employment, were brought in by Harold Wilson’s government to prevent a situation like that in Bristol occurring again.

“I met him at the House of Commons,” says Stephenson. “He made it quite clear he was going to do something against racism.”

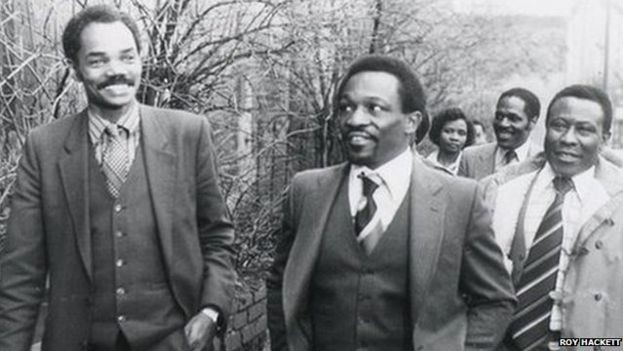

Bailey, Hackett and Stephenson were all subsequently awarded the OBE for the part they played in the boycott.

Their names may not be as recognisable to most Britons as those of King and Parks are to most Americans, but all remain quietly proud of their achievements.

Those who found themselves on the other side of the barricades feel differently.

Tony Fear celebrated when the bar was lifted. Before this, he argued against discrimination with his fellow bus workers, but never went to any union meetings to state his case because he disagreed with the concept of the closed shop. Today, he wonders if he should have done more.

“When you get to my age, you think: ‘I should have said this, I should have stood up,'” he says.

Bishop, who now has two mixed-race grandchildren, kept quiet at the time, something he now regrets.

“When I was a callow youth, I wasn’t much concerned about it,” he says. “But later I felt guilty about it. You get more aware of it as you get older.”

Their union eventually voiced its remorse, too. Unite, into which the TGWU merged in 2007, issued an apology in February 2013 for siding with management 50 years earlier.

However obscure the dispute remains today, Britain’s post-colonial legacy was shaped by its contortions. It began in a bus company office, when a young man walked up to reception.