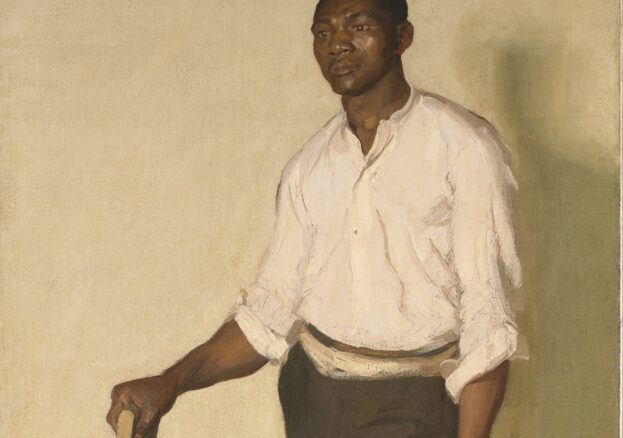

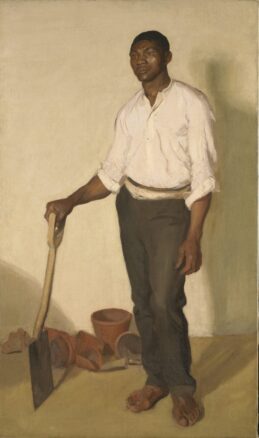

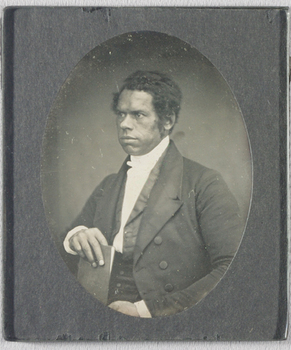

‘Painted in America!’ bellowed the auctioneer in a last throw the night at Christie’s that we acquired Harold Gilman’s ‘Portrait of a Black Gardener’.

‘Who says?’ I exclaimed at the back of the Great Room. True, there was a theory that Harold Gilman painted the picture when, in 1905, he travelled to Chicago to meet the family of his new wife, Grace Canedy. Just a theory. But it was being dangled in front of American buyers.

There were two bidders left: a mystery telephone bidder, and us. We had made the very last bid we could. For one long second, then another, the auctioneer’s hammer paused. Then: ‘Gone to the buyer in the room’. I sank my sweaty brow on the pin-striped back of the man in front (a plush stranger, who gave me a pretty odd look).

Eight days earlier, I had been having lunch with a Trustee, and mentor, the late Giles Waterfield, when we opened the Christie’s catalogue with the sale of the collection of Peter Langan, the restaurateur. And unfolded this beautiful, enigmatic picture. ‘The auction is next week’, I said, ‘I think you should have a try’ said Giles.

We had to raise £135,000, and for several nights I squinted into the small hours at grant application forms; we were supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, The Monument Trust, and Art Fund, and two private donors (each of whom had been struck by the handsome figure when dining at Langan’s restaurant.

When a Museum plans to bid at an auction, it’s wise to keep it a secret. (Why? Because a dealer alerted to your interest may buy the work, ask more, and wait). So you cannot appeal to Friends or public. By Monday we needed a final £30,000 more. A supporter of the bid said: ‘Ask the RHS. Ring up Elizabeth Banks [then President of the RHS].’ I can’t just ring her up at home, I replied; you have to, she said. The RHS pledged £30,000, in the understanding that we could share the display of the picture.

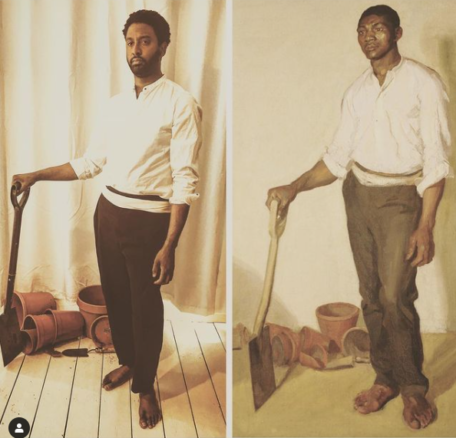

If our rival on the telephone had made a single further bid, ‘Portrait of a Black Gardener’ would have vanished from public sight for ever. But ever since that night in 2014, the picture has hung in pride of place at the Museum. Its proud beauty has been confirmed by its role in the debate on black identity and heritage begun by ‘Black Lives Matter’. In Bedford, a locked-down baritone singer named Peter Brathwaite began a project to dress up as black figures of the past, aiming “to amplify voices and figures that have been historically marginalised within the canon of Western Art.”

And his post was picked up by a young boy at school in Harlem:

So, our picture does have an American existence.

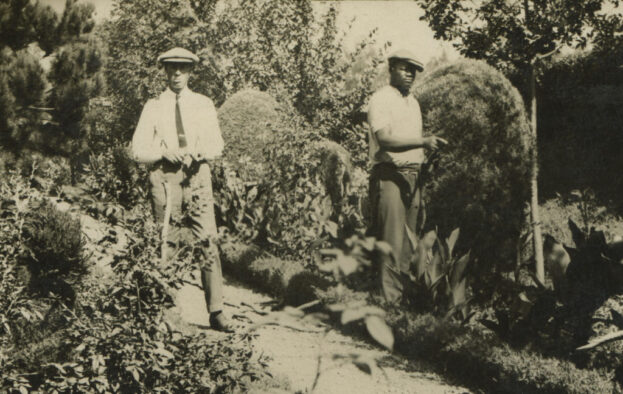

The suggestion that it may have been painted on Gilman’s visit to Chicago was first made by the art historian Ben Nicolson in Apollo Magazine in December 1972. It was just a speculation but reflected, we imagine, an assumption that in 1905 Gilman was more likely to see a black gardener in America at this time than in Edwardian Britain.

But the surprise came when historian Jeffrey Green spoke at a conference on ethnicity in garden history which we held in partnership with the Black Environmental network (BEN), In his work on the black presence in late 19th-century Britain Green showed many examples of gardeners, perhaps the best-known is Thomas Freeman (1809 – 1890), Head Gardener to Sir Robert Harland at Orwell Park, in Suffolk, who became a missionary on The Gold Coast, from where he sent samples of tropical flora to Kew Gardens.

Horticulture Week has just published a piece by Zehra Zaidi, founder of We Too Britain, on John Ystumllyn, a gardener – and florist – for the Wynn family of Gwynned. In 1746, at the age of eight, Ystumllyn was abducted from his family in Africa, and came to the Wynn household, where he was placed in the garden; he is the first black person to be recorded in North Wales.

Gilman’s ‘Portrait of a Black Gardener’ is the first full-length portrait of a sub-Saharan African in 20th-century British art in which the subject stands alone, as an individual, and not as part of someone else’s story. Why did Gilman paint such a picture? Gilman, a rector’s son born in 1876, felt himself ‘roughly handled by life’, according to his closest friend. He became an observer of the less fortunate figures of life and, in politics, a Socialist. And Gilman was a gardener: in 1908 he bought one of the first plots in Letchworth Garden City. He died in 1919 of the Spanish flu pandemic, at just 43.

‘Portrait of a Black Gardener’ is a young man’s work, then, and perhaps that is one reason why on its arrival at the Museum he caught the imagination of children in our story-telling sessions – and of an art teacher in Harlem at a time of crisis and anger. And this is a time when, I think, it is good to be jolted by the ideals of the young.