Living And Travelling With Darcus Beese’s Memoir, ‘Rebel With A Cause’

Last August, whilst coming from the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton, south London, where I attended an interesting programme organised by Royal Holloway University of London about the life of the composer and BTWSC NARM Role Model Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, I noticed from the sign above the nearby Brixton Ritzy Picture House cinema that there was a Darcus Beese book signing.

I knew of his father’s biography – the superbly detailed 2013 published ‘Darcus Howe A Political Biography’, which one of the co-authors Robin Bunce, was kind enough to get the publisher Bloomsbury to send me a copy – but I hadn’t realised that Darcus Jr also had a book out.

It would seem this is the first time a British African father and son have had their individual memoirs published – I’m happy to stand corrected.

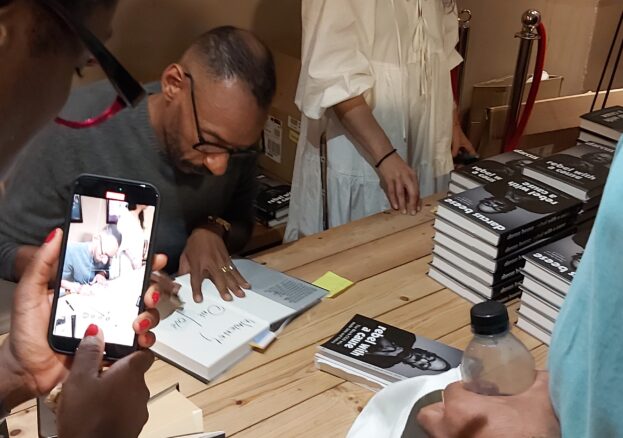

I popped into the Ritzy common area, which was throng with people who had come out of the author Q&A with BBC 1Xtra talks presenter Richie Brave – it turned out we follow each other on Twitter, but hadn’t met until then. Anyway, there were many people who had bought copies of Darcus’ Nine Eight Books-published ‘Rebel With A Cause: Roots, Records And Revolutions’, who were waiting in line for the author to sign their copies.

Whilst waiting to have a chance to "yab” Darcus for my not being in the know about this do – of course it wasn't his fault, I'm simply not on the radar of the Dark Matter and Pester PR companies – I met a whole lot of people from back in the day British black music scene!

I didn't immediately recognise Jaime D'Cruz, who was editor of Touch Magazine, and now creative director at Acme TV. Having lost his hair didn't help. Of course, I've lost some teeth since those days when we used to meet in Touch's Brixton base to pitch feature ideas, etc. Jaime reminded me that I used to give him trouble having to sub my over-long articles, just like this one. Of course, with print media, unlike web-based mags and blogs, there was a physical space limit. Jamie – we need to tell that Touch Magazine story!

Then there was the ever-smiling Paul H, photographer for mags like Hip-Hop Connection, of which I was a contributor. This man owns the hiphop.com domain, which I found out from an old Guardian article that he had been offered a 7-figure dollar sum to sell!

Interestingly, I met someone who uses hiphop.com as her email server – content strategist and “Harlesden girl” Jay – by the way, I’ve ended my community events, so no more street marketing across Harlesden!

I didn’t see the amiable Shane, head of Island’s press, who I later discovered took that very commanding portrait of Darcus, which is used on the book’s cover.

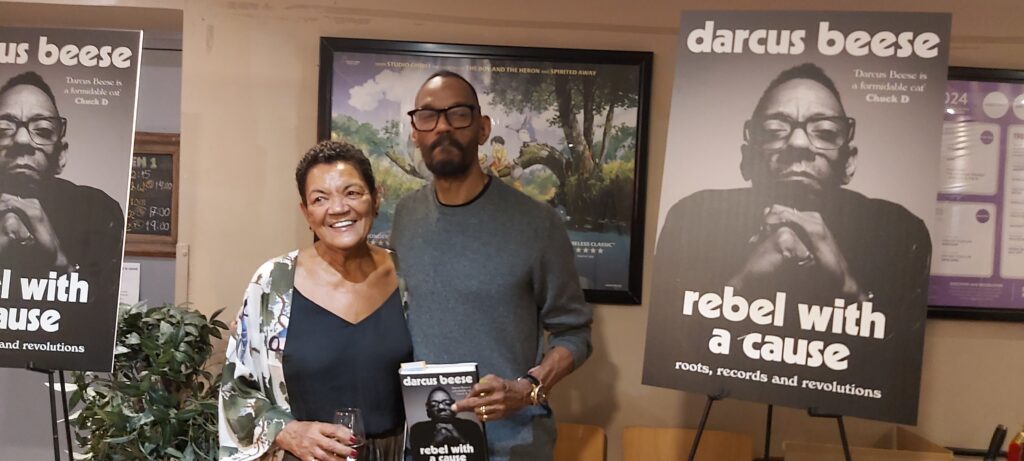

It was however an absolute pleasure to meet Darcus’ mum, Barbara Beese. Being a history researcher, I have written about and organised events where there have been an intersection with British African women, including the women of the Mangrove Nine, of which she’s one. And whilst I hadn’t managed to get Barbara on board, we did organise a well attended Living Histories Q&A event in 2016 that featured her Mangrove Nine colleague Altheia Jones-LeCointe.

My first observation after she introduced herself was how youthful the septuagenarian looked! Indeed, I had to let her know that she had been blessed with such a beautiful, youthful air about her. I won’t be surprised if she has her memoir in the works. If not, then I’d encourage her to, as it would add greatly to British social history. Anyway, I just had to take a photo of mother and son, which they obliged, as soon Darcus was done with signing the books and we’d exchanged pleasantries.

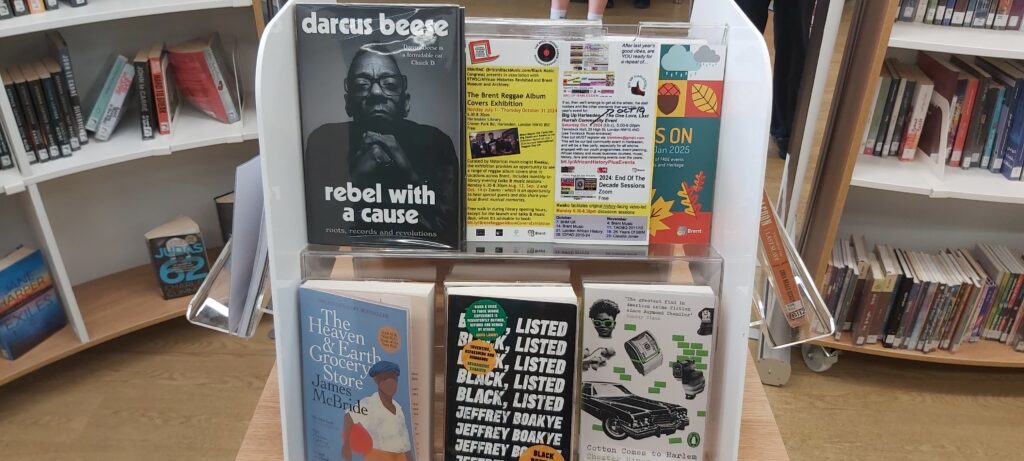

Next, I had to find out from the afore-mentioned PR reps how to get a review copy. These days, I seldom write book reviews – interestingly, one of the last ones was another Nine Eight Books publication – the memoir of Darcus’ mentor and former boss, Chris Blackwell’s ‘The Islander: My Life In Music And Beyond’, which I got in the Black History Month magazine and the Weekly Gleaner. The later newspaper has also published my ‘Discover The Story Of Darcus Beese’ review in the March 27-April 2 2025 edition.

Thanks to Pester PR, I duly received a copy of Darcus’ book. Initially, I had hoped to publish a review within the UK African History Month window of October. However, that was not to be, because even though I carried the book with me on my tube travels across London, which included a chance to pose with it at an Ozwald Boateng do my daughter invited me to, on the plane to to Denmark with my daughter, and to Ghana, a hectic life and lack of clear head space meant I could not find the time to write until recently.

So now to the book I’ve lived and travelled with for months. It was exciting reading a book by the son of two renown community activists, and someone who has excelled within the music industry in the UK and the US.

For the rest of the world who mark Black or African History Month, last month was the month to engage with some form of African history. Of course, some of us think that African History Month should be every month. If you think so, then now is as good a time to check out, if you haven’t already, Darcus’ memoir.

Considering the challenges I’m going through during my present sabbatical trying to put together a book, I particularly applaud Darcus for holding down a job and finding time to deliver such a compelling and inspiring account of a trailblazing career in the music industry, which is interwoven with a deeply personal narrative of resilience, activism, and cultural impact.

The book chronicles Darcus’ remarkable journey from a teenage apprentice hairdresser, or should that be colourist, in a West End salon, to becoming the first African president of Island Records, one of the UK’s most influential record companies. We’re talking about the home label of Bob Marley, U2, and acts developed during Darcus’ tenure such as Amy Winehouse, Florence + The Machine, Sugababes, and Mumford & Sons.

Of the less celebrated acts, Darcus briefly mentions UK rap act Silent Eclipse, whose ‘Psychological Enslavement’ album deserved to cross over, as it showcased the kind of incendiary brilliance akin to Public Enemy. But then in the mid-1990s UK rap seldom made it into the singles chart much less the album chart. In the US, Darcus talks about the Skip Marley project, which didn’t quite blow up in spite of his legendary musical heritage.

Growing up in working class west London with Black Power politico-head parents, this is a rags-to-riches tale that transcends the music business, offering a profound reflection on identity, equality, and the power of perseverance in the face of systemic challenges.

Darcus’ story begins in a politically charged and musically vibrant era, shaped by his African and European friends of his youth and by his parents, Darcus Howe and Barbara Beese, both prominent activists and members of the Mangrove Nine, who fought against racial inequality in Britain during a time when racism, or more specifically Afriphobia, permeated every level of society – from the streets to institutions.

This upbringing instilled in Darcus a fierce sense of justice and determination, qualities that became central to both his personal life and professional achievements. His early foray into the music industry as a teaboy at Island Records, under the mentorship of legendary founder Chris Blackwell, marks the start of an ascent driven by talent, grit, and an unerring ear for potential.

The memoir shines brightest when detailing Darcus’ role as an A&R executive. His ability to spot and develop raw talent is portrayed not just as a professional skill, but as an extension of his belief in giving voice to the underrepresented – a legacy of his parents’ activism. Not unsurpringly, he was honored with The Strat at the 2019 Music Week Awards. And he got an OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire) “for his services to the UK music industry” – read the book to find out what Darcus Sr, the radical, said to Darcus Jr, when the latter told the former about the offer of this Establishment gong.

Darcus doesn’t shy away from the challenges he faced, including industry politricks, corporate pressures, and the personal toll of success, such as his eventual disillusionment when he moved to New York to head Island Records US. These moments reveal a man who, despite his achievements, remained anchored to the values of equality and authenticity.

What sets the book apart is its dual narrative: it’s both a mainstream music industry memoir and a testament to the enduring impact of African Caribbean family and cultural heritage. Darcus’ candid reflections on his parents’ struggles, his own encounters with Afriphobia, and the broader socio-political context of his life add depth, making the book resonate beyond industry insiders.

This is a “rebel” book from someone whose mother was dragging him to political meetings and demos before he was in his teens – there’s a famous photo of 6 year old Darcus with his mother in the front of a 1976 anti-racism march through Brick Lane, east London. The other person, much out of frame, holding Darcus’ hand was Barbara’s former British Black Panther Movement colleague Mala Sen.

Darcus’ story-telling is warm, conversational, and occasionally raw, as seen in his honest recounting of family dynamics, and the weight of living up to activist legacies.

Critics and peers, from Chuck D to Annie Lennox and Bono, have praised Darcus as a “formidable” and “inspirational” figure, and the book lives up to this billing. However, some might find its focus on personal struggle occasionally overshadows the music business insights, though this balance is part of its charm. It’s less a “how-to” guide for aspiring executives and more a story of how one man – a British African, and a Trini – navigated a system stacked against him, emerging not just as a success, but as a cultural pioneer.

Ultimately, this book is essential reading for anyone interested in music, social justice, or the intersection of the two. It’s a tribute to the power of music as a force for change and a reminder that true rebellion lies in staying true to one’s principles. Darcus’ legacy, as detailed in this gripping autobiography, is not just in the hits he helped create, but in the doors he opened for future generations. For those seeking inspiration in a world still grappling with inequality, this book is a beacon.

Darcus’ unorthodox approach and sharp instinct for talent disrupted industry norms, and his late-diagnosed ADHD adds a poignant layer, explaining his restless drive and occasional professional missteps. The condition, once a source of frustration, becomes a lens to understand his creative brilliance and personal struggles.

Darcus is certainly a maverick, and the ‘Rebel’ in the book’s title is apt. Long before the internet made the independent route viable, as a guest at one of our early 2000s Black Music Congress forums at City University London, I recall he urged artists to go the indie route, even though he worked at Island, which was a long-standing major company. And now that he’s left Island, his Darco company focuses on artist partnerships, rather than the normal record company model.

Indeed, years ago when I visited Darcus at the Island HQ in west London to interview him for the BTWSC NARM Role Model project, he proudly mentioned the young ones he was naturing, such as the then A&R newbie Ben Scarr. Not surprsingly, Darcus, who sees himself as a thought leader, is still pushing for more non-European music executives and EDI (equity, diversity, inclusion) programmes, despite resistance from the likes of President Trump!

Let me end by repeating that this book is both a celebration of cultural identity and a candid exploration of how neurodiversity shapes success. Darcus’ voice is authentic and inspiring, making this memoir essential for those interested in music, race, and the triumph of individuality.

Kwaku is an independent history researcher and historical musicologist.