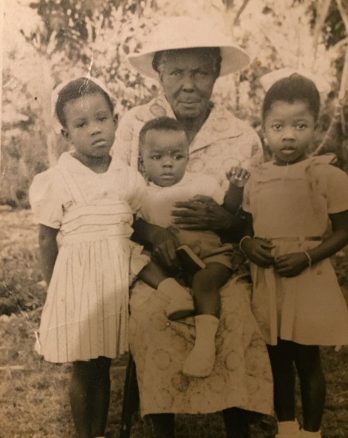

My grandparents knew nothing of Africa. My great grandmother was born in 1882 what did she know of Africa? Indeed the queen sent her a birthday greeting for her 100th birthday. Her mother, granny Yaya spoke nothing of Africa only that her mother was 5 when slavery was abolished and then only with some remote disconnection as if it were a romantic period. They knew nothing excepting that it was a place on a map that no one spoke of. Certainly, they had no intentions of ever venturing there. They knew nothing excepting the beautiful isle Jamaica where they had lived for generations and from time to time a member of the family would venture to Cuba or maybe the South Americas.

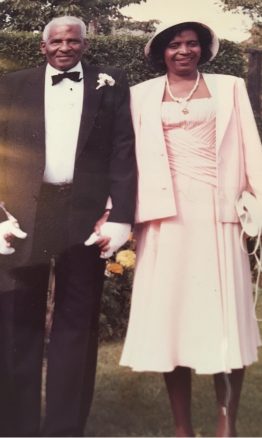

My father had already been here 9 years, my mother 7 years. She was teaching as she had done in Jamaica before coming here but by now she had retrained at Whitelands Teacher Training College so had all the right educational criteria required to teach here.

My father owned trucks – tipper lorries. England was booming at that time, still suffering from the effects of WW11, these post war years offered many opportunities for many industries and the construction industry was no exception. Children still played in the streets at that time and when my parents allowed my siblings and I, we would be out there too often chanting songs with our neighbours…”We Won The War… we won the war…” New roads were being built, houses and towns were being built. My father would haul sand, muck, stones and anything that was needed from one end of the country to another. Liverpool, Southampton, Staines, the A40. These were just some of the names I remember and with great delight I would accompany him during the holidays on the “tippers” to collect the goods then drop them off elsewhere. The sound of the engine humming loudly as we sat high up in the cab, sometimes nodding off to be wakened by my father’s voice say “Joy, we reach” . The only dreadful part of the journey was on arriving, when the lorry would be put into tipping mode to offload the goods. He would get out of the cab and greet Mick (so many Irish people had that name in those days) and I would be left alone in that mini room (the cab). It would bounce up and down, shake from side to side and he would pop back from time to time to fiddle with something or other near the enormous steering wheel then quickly jump out again – before I could get the chance to say “I think I’m about to be killed” . As he supervised the offloading the truck rumbled, bounced and shook from side to side. When the load had been finally dumped he would return joyfully to the truck. Hauling and dumping meant money, by which time on seeing him I was perfectly composed and happy. Of course I would be, the ordeal was over! I never ever did mention to him how fearful I was and of course, the truck never toppled, no such thing could have happened although I didn’t know that at the time. Other than that there were just lone drivers through the countryside and on fairly new motorways. In the blackness of the night at times he would explain about the “cats eyes” in the road which in fact were markings which would glow enabling drivers to see their lanes clearly. I hadn’t really understood and literally believed they were the eyes of real cats and gave a great deal of thought as to how the other parts of the cats bodies were invisible.

England was the first place that my parents had ever come into contact with Africans. Not Nigerians, not Ghanaians nor Gambians, just plain Africans. They were deemed different, a legacy of the colonies and precolonial days. “Best not to speak with them, they were not the same as us – Jamaicans”. I might add here that it was also best not to talk to anyone from any of the other Caribbean islands either as they were also different – tales abound about cat and monkeys being corned and stored in tiny back gardens in preparation for feasts were abound. Indeed a neighbour had a corgi which one day disappeared and the last I heard after great searching and tumult was that another neighbour had been accused of cooking and eating eat.

My parents had a house with tenants and they rented a room to a lovely refined couple. The Quinis. Mrs Quini loved to have me come a visit her room and she would often ask my mother for permission to comb my hair. I sometimes watched her cook and prepare her husband’s meals which I always thought looked so appetising. Things I’d never seen, a white dough like substance with delicious smelling stews. One day, she asked my mother if I could come for tea and my mother agreed. I was so looking forward to eating that stew only to be disapppointed. She had prepared eggs and baked beans for me to eat and I was far too polite to object. I had no interest to go back and visit Mrs Quini after that and in any case they left soon after and went back to Yaba, Nigeria. (A place I would visit one day).

It was not until 1976 that I met my first African friend. She was Nigerian an Oxford graduate a few years older than I. She was the opposite in appearance to Angela Davies, whom I had been so impressed with and admired, sporting a semi shaved head (very short hair) and large earrings. She was a wonderful insight for me into a world I knew nothing about and so cultured – both English and Nigerian at the same time and highly politically motivated on issues that I had never given any consideration having grown up in an English environment and my roots were founded in the propaganda of colonialism. We had wonderful and often heated debates and it was then I discovered I had very strong views of my own. She introduced me to a new world of political black, both Africans and West Indian activists some of whom went to to become very famous. She had the most beautiful name – Acqua and was so articulate and opinionated – I was thrilled by her and her “friends” . It was then I discovered that I had more in common with these people that I could have ever imagined. None of the pseudo “apartheid” nuances that I had grown up with existed.

My parents quite humble yet shrewd themselves were from well educated backgrounds in Jamaica and had shielded us from a young age from the waves of immigrants from rural communities, many of whom were uneducated so it was wonderful to discover those groups of diverse people. It was all new to me.

By 1979, having done a stint at Times Newspapers I was working for a publishing house on trade magazines and it was then that I had the opportunity to go to Nigeria, quite unexpectedly. During this era in the UK it had become fashionable to talk about “Roots” and Kunte Kinte was now a household name, however, I was not of that set and yet, I was the one about to go to “Africa” . I suddenly gained some credibility within a small group of so called “friends” in the West Indian community. I must say I did enjoy the esteem and accolade that had sprung up from no where although I did find it a bit strange.

Years later, I learned that my parents had actually been near petrified at the thought of me going but they did not show it so as not to dampen my enthusiasm.

My very first trip was the beginning of a new era in my life which opened doors I never knew existed and I was suddenly swept from one world to another, almost overnight – never to look back!