On 14 October 1997, I took part in my first Black History Month event. I gave a talk about my first black history book, Aunt Esther’s Story, at the Sojourner Truth Community Centre in Sumner Road, Peckham, a small but popular community venue. The event was well attended. In addition to reading passages from the book, I also screened a video recording of an interview I did with the subject of the book, my adopted Aunt Esther, a black Londoner, born before the First World War. It seemed fitting that she would be the subject of my Black History Month debut.

Twenty years have passed since that first event, and I have participated in hundreds of Black History Month presentations since that time. October is the busiest month of the year for me. In addition to grass roots community groups, I visit schools and academies, and I have been invited to many different venues, including the Black Cultural Archives, Imperial War Museum, City Hall, National Portrait Gallery, Globe Theatre, National Army Museum, and various University conferences.

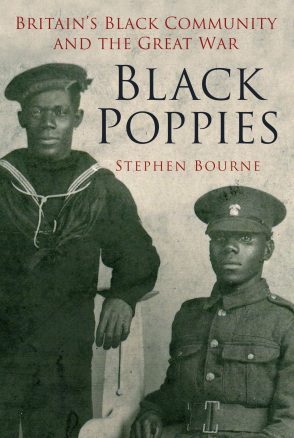

One of the many highlights occurred in October 2016 when I was invited to give a talk about my book Black Poppies at the Houses of Parliament. Black Poppies acknowledges and celebrates the black servicemen of the Great War of 1914-1918 and sheds light on many overlooked achievements. I was overwhelmed by the attendance of over 200 members of the public, mostly black parents with their children of all ages. They were keen for a new generation to learn about Britain’s black past, especially the First World War. I was touched by the positive reaction of the audience, especially the younger members, some of whom asked perceptive questions. They were appreciative of my efforts to bring black Britons from history into the public domain.

I am always worried when criticisms are made about the existence and usefulness of Black History Month. In some respects, this is justified for I have grown increasingly concerned about the distribution of limited Black History Month funds being awarded to groups which stage events that bear no relation to history. The focus on history can be lost. However, when the focus is history, October can be used as a wonderful platform for enriching and enlightening our communities, especially the younger members, about our black British past. However, I would agree that black history events need to be held throughout the year, not just October.

I am concerned that, without Black History Month, British schools and academies will not be presented with opportunities to learn about the history of black people Britain. Except for Mary Seacole and Walter Tull, black Britons are not included in the history curriculum. Our young are more likely to learn about African Americans from history. Black History Month offers opportunities for historians like myself to offer an alternative black history, one that relates to this country.

What makes this work worthwhile is the positive feedback. Last year I was deeply moved by a letter I received from a young black man in prison. He said: “I have just finished reading your book Black Poppies which has given me a rare insight into the lives of early black people of great courage, insight and pride, living, working and standing strong as a unit. This has brought great pride into my life, bringing about a sense of ownership. Looking at the pictures was like seeing familiar faces I’ve observed growing up around me over the years. I was very impressed with the construction and well thought out content of this book. God bless you.”

I am looking forward to celebrating 20 years of participating in Black History Month with more Black Poppies events. One that I am looking forward to is taking place at New Scotland Yard for the Metropolitan Police Black Police Association.

In October 2017 London South Bank University will honour Stephen Bourne with an Honorary Fellowship for his contribution to diversity at their degree ceremony at the Royal Festival Hall.