I recall 1987 not only for the inaugural celebrations, but also for the continuing hostility of how notions of black unity and power divided the political classes. In that year’s general election the Tories claimed that ‘Labour think you’re Black we think you’re British.’ More brazenly they ran a campaign against the loony left wing London Boroughs who were politicising culture and especially schooling with notions of Black History Month and Positive Images for the lesbian and gay community. Now I roll my eyes to see that a Conservative Prime minister accept that Black History Month is an essential part of the cultural calendar.

So when these same boroughs began to celebrate Black History in the first festival of it’s kind in 1987, the hostility and negativity it created was nothing less than a virulent reactionary backlash to blackness. We were accused of wasting local ratepayers money, dissing the glories of empire and mocking true historical facts. Only the second was true and it was absolutely needed in classrooms where Britain’s slave trade was ignored, the persecution of indigenous cultures obliterated from textbooks, and the imperial legacy of divide and rule lay unscrutinised.

I believe that that the intervention into the history curriculum is one, if not the most important enduring legacies of Black History Month and the festival’s positive contribution to recasting imperial largesse, shouldn’t be taken for granted.

At the same time as Black History Month was being launched we were also trying to heal any perceived and actual divisions within the African, Caribbean and Asian communities. Then, it was a powerful message to say that Black meant inclusion for all. As Linda Bellos so rightly points out, it may have been better if we had termed the annual celebrations, African History month. Like hundreds of thousands fellow East African Asians I was born in Kenya, whilst others immigrated from Tanzania, Uganda and Malawi to name but a few. How do we fit into notions of Black History?

Some argued that we simply don’t or more rightly, shouldn’t . I remember being attacked at one Black History Month event at the Museum of London when I joined Trevor Phillips and David Lammy on a discussion panel, as not being Black. Despite being born in Africa and for example, one of my cousins competing for Kenya as a swimmer in the All Africa Games, I was lambasted for not being African enough. So surely notions of African history must be diverse enough to include the experiences of my cousin, whose wife is the daughter of the Ghanaian poet and novelist, Kojo Laing.

Not content with challenging my ethnicity, I have also been challenged in discussions about the inclusion of the Black LGBT community. It’s really only in this century, that we have overcome initial fear based on ignorance, that issues of Queer culture are not compatible with notions of Black History. And long may this continue.

So when we think from where we started to where we have come to, there’s a lot to appreciate and to recognise that even expressions of what constitutes Black History aren’t static and immovable. Maybe it’s time to call our distinctive celebrations Black British History month.

So when we think from where we started to where we have come to, there’s a lot to appreciate and to recognise that even expressions of what constitutes Black History aren’t static and immovable. Maybe it’s time to call our distinctive celebrations Black British History month.

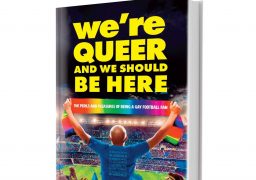

Darryl Telles is the author of the book ‘We’re Queer and we should be here’ which describes his experiences of combating racism and homophobia in football.