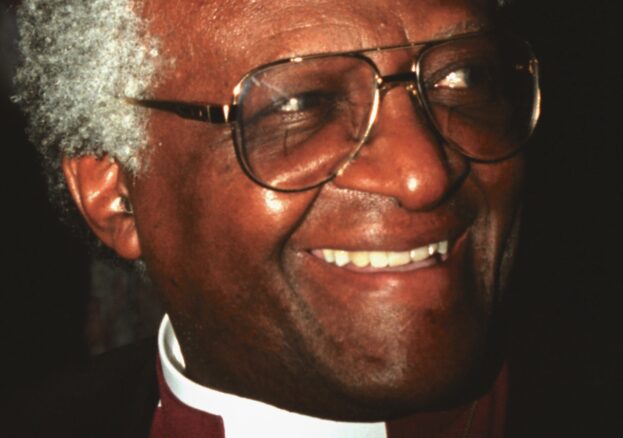

Emeritus Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu was the smiling and laughing South African archbishop whose irrepressible personality won him friends and admirers around the world.

As a high-profile African churchman, he was inevitably drawn into the struggle against white-minority rule but always insisted his motives were religious, not political.

However, through his personality, he made an enormous impact wherever he went around the world, meeting presidents, celebrities but not forgetting or ignoring the problems of the common people too.

Tutu, a transcending figure in South Africa’s liberation struggle, died on 26 December 2021 at the age of ninety.

Like the medieval St Thomas Beckett, he was also a” turbulent priest,” much hated by secular authority.

Archivists will remember his stirring keynote address to the 2003 Cape Town CITRA Conference on Archives and Human Rights.

In many respects, this conference charted a new course for the ICA and led to the establishment of the section on Archives and Human Rights.

Desmond Mpilo Tutu was born in 1931 in a small gold-mining town called Klerksdorp in what was then the Transvaal.

He suffered from several serious childhood illnesses, including polio.

Despite his parents’ modest circumstances, he managed to get a good education and trained to be a teacher, one of the very, very, few occupations open to educated Black people in the 1950s.

While he was teaching, he met and married his wife Leah, and the couple had four children.

The imposition of apartheid restrictions on black education was one of many factors that decided him to become a priest. However, he gave most of the credit to Father Trevor Huddleston, an early critic of apartheid, for awakening his sense of faith and of mission.

Trained in London

After training at South African seminaries, the Anglican Church sent him to King’s College London, for post-graduate studies.

He studied theology at King’s. He completed both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree here, graduating from the latter in 1966.

Desmond said of his time at King’s: “I have wonderful, happy memories. My experience was one of great encouragement and support in my academic studies and an acceptance and warmth from my fellow students.”

“Study opened up a whole new world to me. I was excited by the accessibility of books, the freedom to question and to debate and the opportunity to listen to the wisdom of minds whose experience and learning left me eager to discover more.”

Returning to South Africa he advanced rapidly up the Church hierarchy and was elected as General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches.

The SACC was a major critic of apartheid and in this role Tutu’s criticisms of the repressive policies of the government earned him the title of “Public Enemy Number One.”

Tutu not only attacked the National Party Government from podiums and pulpits, but he worked practically on the ground to alleviate human suffering and uplift the poor.

He showed much physical courage in facing down riot police and in calming rampaging mobs.

He was also credited with coining the term Rainbow Nation to describe the ethnic mix of post-apartheid South Africa.

He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984.

In addition to his moral and physical courage, Desmond Tutu had a delightfully wicked sense of humour that he deployed to defuse tense situations and to gently mock the pompous and the oppressive. One of his most famous remarks was:

“When the missionaries came to Africa, they had the Bible, and we had the Land. They said, “Let us pray.” We closed our eyes. When we opened them, we had the Bible, and they had the Land.”

Archbishop in 1986

He was installed as Archbishop of Cape Town and head of the Anglican Church in Southern Africa in 1986, an office he held for ten years.

He faced down apartheid State President PW Botha who removed his passport to prevent him rallying anti-apartheid sentiment overseas.

During the fraught years leading up to the first democratic election in 1994, Tutu strove to reconcile blacks and whites as well as various factions within black communities that were involved in violence against each other.

He was never afraid to voice his opinions. In April 1989, when he went to Birmingham in the UK, he criticised what he termed “two-nation” Britain and said there were too many black people in the country’s prisons.

As democracy dawned, his term as Archbishop of Cape Town was coming to an end and the new President, Nelson Mandela, appointed him to head the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the TRC.

Tutu played a vital role in Mandela’s policy of reconciliation. In this role he sought to bring about national reconciliation despite opposition and controversy from right and left.

The Arch weeping

Who can forget the pictures of “The Arch” as he became known, weeping as he listened to the most harrowing testimony?

The archbishop was one of the most prominent exponents of human rights in South Africa, with a worldwide reputation.

He had not given up campaigning with the advent of democracy. As the gloss dimmed on the South African democratic experiment, Desmond Tutu became one of the most vociferous critics of corrupt politicians and devious practices.

Repeatedly he reminded the nation of its ideals and of those who had suffered and sacrificed to build a democracy. Sometimes he managed to shame venal politicians into changing their conduct, or at least hiding their misdoings a little better.

Founding Elder

Internationally, he was one of the founders of the group of Elders, including former UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, Former US President, Jimmy Carter, Nelson Mandela’s widow, Graca Machel, and former Irish President, Mary Robinson.

The group was founded to mediate in difficult conflicts, reduce tensions and avert violence. Tutu was also a supporter of Palestinian rights but carefully distinguished between the people of Israel and the policies of their government.

Tutu formally retired from public life in 2010 to, he said, spend more time “drinking red bush tea and watching cricket” than “in airports and hotels”.

But ever the rebel, he came out in support of assisted suicide in 2014, stating that life should not be preserved “at any cost”.

Very few people can make such an impact around the World. Desmond Tutu had the ability to make people listen and smile.

A small man, “the Arch”, as he was known, was gregarious and ebullient, emanating a spirit of joy despite his intense sense of mission.

He was witty, and his conversation was frequently punctuated by high-pitched chuckles.

But beyond this, Desmond Tutu was a man of impeccably strong moral convictions who strove to bring about a peaceful South Africa.

Perhaps his own words best sums up the great man:

“I wish I could shut up, but I can’t, and I won’t.”