February is recognised as Black History Month in the United States. Since the country’s bicentennial in 1976, Black History Month has been an official designation to honour and remember the significant and immeasurable impact African Americans have had on the nation. President Gerald Ford said the annual observance was to “honour the too-often neglected accomplishments of black Americans.”

Here, Dance Informa reflects on the black dancers who significantly impacted the American dance scene, as well as the major companies who pioneered a new world where black dancers could be seen as equal artists.

Master Juba (1825-1852)

It’s likely many dancers have never heard of Master Juba due to the fact that his important dance contributions sadly go hand-in-hand with performances that reiterated racist stereotyping. He performed in minstrel shows, an American entertainment in the 19th century that consisted of comic skits and dancing in blackface.

Yet, what most people look at skeptically – a black freeman performing in minstrel shows that lampooned black people as dim-witted, lazy and overly happy-go-lucky – was actually an achievement for a black man in his time. In the antebellum era when blacks were not allowed to perform with whites, Master Juba was the first to attain acceptance and notoriety as an entertainer. In his career he performed with four well-known early minstrel companies and later became the first expatriate black dancer, moving to Europe and never returning to the United States – a huge accomplishment.

Yet perhaps most significantly, Master Juba (who was legally named William Henry Lane) was the first known dancer to combine quick footwork with traditional African rhythms, leading to the creation of tap dance and even elements of step dancing.

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson (1878-1949)

While many were probably new to Master Juba, I’m fairly certain most have heard of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Known as the father of tap dance, Robinson is most famous for his appearance in the widely popular movies starring child actress Shirley Temple. In his career, Robinson appeared in a total of 14 films and six Broadway shows, sometimes in prominent roles – an enormous triumph for a black actor in his day.

In addition, Robinson was the first black solo performer to star on white vaudeville circuits, where he was a headliner for four decades.

Robinson was known for gentle, intentional movement combined with austere musicality.

Asadata Dafora (1890-1965)

Asadata Dafora was a dance pioneer in bringing authentic West African culture to audiences in the United States. A dance form that was virtually unheard-of at the time, African dance opened a door to a new study of cultural dance and performance.

Originally from Sierra Leone, Dafora first came to the states in 1929. He soon thereafter formed Shogola Oloba, a dance and singers troupe, to present movement-based dramas based on West African myth and lore. Dafora was the first known artist who endeavored to present authentic African forms outside a tribal setting. He influenced artists like Pearl Primus who later incorporated African elements into her choreography.

John Bubbles, a 2002 Inductee into the American Tap Dance Foundation’s International Tap Dance Hall of Fame. Photo courtesy of ATDF.

John W. Bubbles (1902-1986)

Like Robinson, singer and dancer John W. Bubbles made significant strides in the progression and commercialization of tap. Starting his career at 10 years old, Bubbles joined six-year-old dancer “Buck” Washington to create a singing-dancing-comedy act. With Buck, Bubbles became very popular. The two performed an act in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1931 and became the first black artists to perform in New York’s acclaimed Radio City Music Hall.

Bubbles, who is perhaps best known for performing as Sportin’ Life in George Gershwin’s 1935 production Porgy and Bess, later went on to perform in Harlem’s famous Hoofers Club, which led to Broadway gigs, which led to opportunities in Hollywood.

Bubbles is said to be the first dancer to fuse jazz dance with tap, a frontrunner for many jazz-tap companies that exist today. He created off-beats and in turn, altered accents, phrasing and timing.

Josephine Baker (1906-1975)

One of the first black women to leave her mark on the dance world, Josephine Baker’s legacy is synonymous with sensuality, bravery and uninhibited passion. Born in St. Louis, Missouri, Baker grew up with little and quickly developed an independent spirit, learning to provide for herself and make her own way. This free and bold behavior led her to perform across the country with The Jones Family Band and The Dixie Steppers in 1919. By the time she sashayed onto a Paris stage during the 1920s, she was confident in her abilities and performed with a comic, yet sensual appeal that took Europe by storm.

Famous for barely-there dresses and modernized movement, Baker went on to perform and choreograph for 50 years in Europe. Although racism in the States often restricted her from gaining the same renown at home as she did abroad, Baker fought segregation through organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The organization actually named May 20 “Josephine Baker Day” in honor of her efforts.

In her lifetime, it is said she received approximately 1,500 marriage proposals and countless gifts from admirers, including luxury cars. On the day of her funeral, more than 20,000 people crowded the streets of Paris to watch the procession on its way to the church. Baker was the first American woman buried in France with military honors.

Katherine Dunham (1909-2006)

Some dance historians have named Katherine Dunham the most important women of African American dance. Dunham was one of the first modern dance pioneers in her own right, combining cultural, grounded dance movements with elements of ballet.

Dunham, who was born in Illinois, began her formal study of dance in Chicago where she trained with modern and contemporary ballet pioneers while simultaneously studying anthropology. In the 1930s, she completed a 10-month investigation into the dance cultures of the Caribbean. She brought what she learned back to America, developing a new revolutionary aesthetic that merged the rhythms of cultural dances with certain components of ballet.

For two decades, from the 1940s to the 1960s, Dunham’s dance company toured the world – from the United States to Europe to Latin America to Asia and Australia. She also founded a school to teach her technique in New York.

Honi Coles (1911-1992) and Charles “Cholly” Atkins (1913-2003)

Performers Honi Coles and Charles “Cholly” Atkins are paired together because of their contribution to dance as longtime tap dance partners. After serving in World War II, Cholly, who already had significant experience as a tap dancer, formed his most celebrated partnership yet with high-speed and self-taught rhythm tap dancer, Charles “Honi” Coles.

Teamed up, the duo significantly advanced and promoted the art of rhythm tap dancing. They toured with the big bands of Duke Ellington, Count Basie and Cab Calloway, as well as made short films for television. The pair was significantly well known for their slow soft-shoe routine Taking a Chance on Love. In 1965, they were even featured in a CBS-TV Camera Three program.

From this notoriety, Cholly eventually became staff choreographer for Motown Records from 1965-1971. He created a new dance genre, vocal choreography, which eventually won him recognition from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1993. On the other hand, Coles made it big on Broadway, winning a Tony award in 1983 for his role in My One and Only and later, a National Medal of Arts for his contribution to dance.

Fayard Nicholas (1914-2006) and Harold Nicholas (1921-2000)

Better known as “The Nicholas Brothers,” Fayard and Harold Nicholas both had unique careers as tap and “flash” dancers. They got their first big gig at the Cotton Club in 1932, with Fayard at 18 and Harold at just 11 years old. Following appearances with big bands, they became very successful in Hollywood.

The Nicholas Brothers lite up the screen in movies like Kid Millions (1934), Down Argentine Way (1940), Stormy Weather (1943), and St. Louis Woman (1946). They even performed in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1936 and Babes in Arms.

Before they retired, Fayard contributed choreography to the 1989 production of Black and Blue and Harold performed as part of the 1982 Sophisticated Ladies national tour and in The Tap Dance Kid on Broadway in 1986.

The brothers have received Kennedy Center Honors and have had the documentary The Nicholas Brothers: We Dance and Sing made in their honor.

A biography on the life of Janet Collins was published a few years ago by dance historian Yael Tamar Lewin. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Janet Collins (1917-2003)

Janet Collins, who died just a few years ago in Fort Worth, Texas, was a forerunner for black female ballet dancers. She was one of very few black women to become prominent in American classical ballet in the 1950s, inspiring a generation and giving hope for a more equal society.

Collins began dancing in Los Angeles and eventually relocated to New York. Her big debut was to her own choreography in 1949 on a shared program at the 92nd Street Y. She was well received, being praised for her sharp, technical precision. After performing on Broadway in the Cole Porter musical Out of This World, she was hired as a principal dancer at the Metropolitan Opera House in the early 1950s.

Throughout her career, Collins also danced alongside Katherine Dunham and performed with the Dunham company in the 1943 film musical Stormy Weather.

She danced a solo choreographed by Jack Cole in the 1946 film The Thrill of Brazil, and even toured with Talley Beatty in a nightclub act.

In recognition of Collins’ great work, her renowned cousin Carmen De Lavallade started the Janet Collins Fellowship.

Pearl Primus (1919-1994)

If anyone could contest Dunham’s title of being the “grande dame of African American dance,” it would be dancer, choreographer, director and activist Pearl Primus. Primus is equally important, as she is known to have facilitated a deeper appreciation for and understanding of traditional African dance.

With the help of a grant, Primus spent over a year in Africa in 1948, gathering materials and detailing tribal dances that were quickly slipping into obscurity. She returned to the U.S. and established the Pearl Primus School of Primal Dance. Through her teaching and performances, she not only helped to promote African dance as an art form worthy of study and performance, but to disprove myths of savagery.

In addition to many other accomplishments, she became the director of the African Performing Arts Center in Liberia in 1961, the first organization of its kind on the African continent.

Alvin Ailey (1931-1989)/ Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (1958-now)

Alvin Ailey was first introduced to dance in Los Angeles by performances of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and the Katherine Dunham Dance Company. He began his formal dance training with an introduction to Lester Horton’s classes. Horton, the founder of one of the first racially-integrated dance companies in the country, became a mentor for Ailey as he embarked on his professional career.

After Horton’s death in 1953, Ailey became Director of the Lester Horton Dance Theater and began to choreograph his own works.

In 1958, he founded Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, now a world-class and internationally renowned dance company. He established the Alvin Ailey American Dance Center (now The Ailey School) in 1969 and formed the Alvin Ailey Repertory Ensemble (now Ailey II) in 1974.

In addition to his huge contribution to the furthering of modern dance, Ailey was a pioneer of programs promoting arts in education, particularly those benefiting underserved communities.

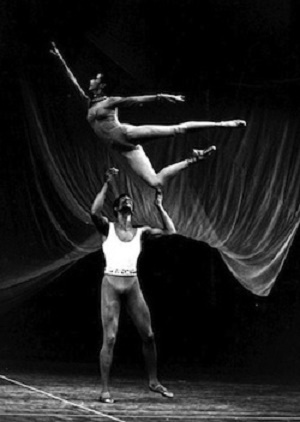

Dance Theatre of Harlem (1969-now)

Founded in 1969 shortly after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Dance Theatre of Harlem was directed by the first black dancer at the New York City Ballet, former principal Arthur Mitchell. Dance Theatre of Harlem, known as the oldest black classical company in continuous existence, allowed and encouraged more black ballet dancers to dance professionally.

Originally, the repertory was neoclassical in orientation with several ballets by George Balanchine. In the 1980s, more contemporary works and classics were added. The company also presented various works by black choreographers, including Geoffrey Holder, Louis Johnson, Alvin Ailey, Alonzo King, Robert Garland, as well as Mitchell himself.

With many of its dancers going on to perform with bigger national companies, the Dance Theatre of Harlem has been instrumental in lowering the color bar in ballet. The company’s school, which Mitchell initially directed with Shook, has become an international force as well as a major Harlem institution.

*Please note: There are many other noteworthy and historic black dancers and companies who have impacted American dance. This is only a partial list.

Sources:

Dance Heritage Coalition. “America’s Irreplaceable Dance Treasures.” www.danceheritage.org/treasures.html.

American Tap Dance Foundation. “Tap Dance Hall of Fame – Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson.” atdf.org/awards/bojangles.html

Official Site of Josephine Baker. “Biography.” www.cmgww.com.

“Janet Collins, 86; Ballerina Was First Black Artist at Met Opera.” Dunning, Jennifer. New York Times. May 31, 2003. www.nytimes.com.

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. “The Ailey Legacy.” www.alvinailey.org.

Dance Theatre of Harlem. “Who We Are.” www.dancetheatreofharlem.org.