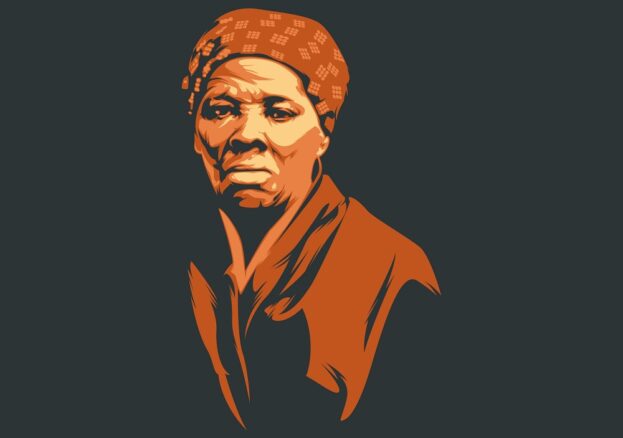

In my first post for BHM 2023, I looked again at the story of Rosa Parks. Today, I will revisit the story of one of the most famous names in the story of abolition in the USA, Harriet Tubman.

Harriet was Born enslaved in Maryland in 1822. In 1849, she escaped to Philadelphia, but her experiences of enslavement were to dominate the rest of her life in more ways than one. The injuries she sustained from beatings left her with lifelong pain and dizziness. She began to experience visions and vivid dreams. She interpreted these as messages from God, but it seems likely that they were connected with a head injury suffered when she was hit with a heavy weight.

She dedicated her life to freeing other enslaved people, beginning with her own family. In all, she made over a dozen trips to free around 70 people. She also served as a scout and a spy for the Union army during the Civil War. Harriet was one of many people, black and white, who formed the ‘underground railroad’ that took enslaved people to freedom and safety.

Many of the narratives about Harriet Tubman have painted an idealised, almost saintly, picture. Like the story of Rosa Parks, this is an example of a long tradition: the co-opting of a prominent Black figure and changing their story to fit another agenda, which is often the creation of an artificial image of an ‘acceptable’ Black person. In reality, Harriet was a freedom fighter, with the emphasis on ‘fighter.’

As well as fighting in the Civil War, she always carried a gun on her missions of rescue and used it more than once to protect her charges. She also used it to threaten those who wanted to go back, because it would endanger the others.

On at least one occasion, she put her revolver to the head of an escapee to force them to go on. She also helped in the recruitment for and organisation of John Brown’s anti-slaveholder raid on Harper’s Ferry. When Brown was executed for leading the raid, Harriet said, ‘He done more in dying than 100 men would in living.’

The treatment that Harriet received after the Civil War was, in many ways, symbolic of what were to be disappointed hopes for the newly free. On one occasion, she was told to move to a cheaper part of a train, despite being entitled to sit where she was. When she resisted, she was forcibly removed, in the course of which her arm was broken. She never received a regular salary for her work and was denied compensation.

She lived out most of her life in poverty, often relying on the support of old friends, and was even swindled out of what little she had. It wasn’t until the mid-1890s, when she was over 70 years old, that she finally received a modest government pension. Even that small gesture required direct Presidential interference.

I salute the real Harriet Tubman, with all her imperfections, her passion and determination to achieve justice, whatever the cost.