The abolitionists were up against some formidable economic interests – and some of them even ended up getting involved in slavery themselves.

The British abolition movement got underway in earnest in 1787 when Thomas Clarkson founded a committee to fight the slave trade. One member, William Dilwyn, was an American Quaker of Welsh descent who ended up owning the Cambrian Pottery in Swansea. His son went to live in Swansea.

Before the debate on the slave trade burst onto the public agenda, campaigners had been laying the groundwork by publishing documents about the cruelty of slavery.

One of those was William Williams of Pantycelyn – who wrote the hymn Bread of Heaven. In the 1770s a number of former slaves published their life stories and Williams was the first to translate one of these into Welsh.

“Williams Pantycelyn was a pioneer in publishing slave narratives in Welsh,” said Dr E Wyn James of Cardiff University.

“Abolition did not become a popular movement until 1787 but you get this preparatory period where people like Williams Pantycelyn are saying that this slave trade is not right.”

Later in the 1790s when abolition was a popular – even fashionable – movement Welsh Christians like Morgan John Rhys are outspoken against slavery. One important evangelist of the time – John Elias from Anglesey – preached against slavery in Britain’s biggest slave port, Liverpool.

“Much was said about the sinfulness of the slave trade when we were in Liverpool recently. We found that some of the brothers were working on the ships which were used in this vile trade, yes, and one of them was forging the chains which would be used to enslave these poor souls; we urged them to abandon his task immediately; we urged everyone not to be involved with any aspect of this cruel institution. It is better to die of hunger than to have plenty of bread by being partakers of blood.”

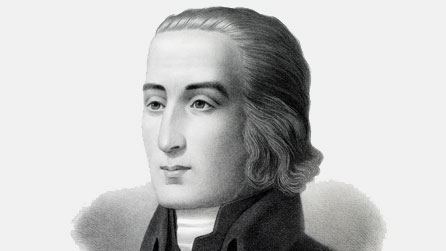

Another ardent anti-slavery campaigner was Iolo Morganwg, a political radical, poet and stonemason whose literary forgeries form the basis of the Gorsedd of Bards.

Morganwg tried to avoid everything to do with slavery. His shop in Cowbridge refused to stock slave grown sugar (the first fair trade shop in Wales) and he refused to take subscriptions for his book from Bristol slave merchants.

But its an indication of the way the slave trade touched so many families that his two brothers were sugar planters in Jamaica, owning 240 slaves.

Initially the impoverished Morganwg refused to take any money from them.

“May the vast Atlantic ocean swallow up Jamaica and all the other slave trading and slave holding countries before a boy or girl of mine eats a single morsel that would prevent him or her of perishing from hunger, if it is the produce of slavery.”

But by 1815 he had taken £100 from the will of one of his brothers. Professor Geraint H Jenkins of Aberystwyth University, leader of a study of Morganwg’s life and works, denies this was hypocrisy.

“He was human and his life was riddled with contradictions. He compromised and said he would accept the money only to pay off his own debts and to set up his son as a schoolmaster in Merthyr,” he told a special BBC Radio Wales programme on links between Wales and the slave trade.

Another Welsh abolitionist who got into similar difficulty was Thomas Coke from Brecon. Coke became the right hand man of John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist Church.

Coke was strongly anti-slavery and preached against it when he was sent to the US to set up the Methodist church there. But he ran into trouble when he reached the slave owning areas of the country.

“The testimony I bore in this place against slave holding provoked many of the unawakened to retire out of the barn and combine together to flog me. A high headed lady also went out and told the rioters that she would give £50 if they would give that little doctor 100 lashes.”

The threat was not carried out – but incidents like this forced Coke to curb his anti-slavery preaching.

Coke later travelled to the Caribbean to set up missions. On the Island of St Vincent the legislature granted him a plantation – and he bought slaves to run it.

This move caused an understandable outcry from fellow abolitionists and he gave the plantation up.

His biographer, Dr John Vickers, says he took on the estate for humane motives.

“I don’t think hypocrisy comes into it. He did it with the best will in the world with the intention of giving the slaves that he owned own a decent life,” he said.

Coke himself admitted the error of his ways saying that he should not have “have done evil that good may come”.

The way even people like Iolo Morganwg and Thomas Coke were sucked into the slavery business despite their moral objections is an indication of the power and the importance of the slave trade to Welsh and British life at the time.

The Welsh abolitionists may have influenced public opinion but they lacked serious power and influence.

When the abolitionists got their day in Parliament in 1789 the most powerful Welsh voice was that of Richard Pennant – the owner of vast slave estates in Jamaica and the father of the north Wales slate industry. As MP for Liverpool he was one of the leaders of the pro-slavery movement.