This documentary follows the research undertaken by the UCL database, which I wrote about here. Currently the first in a multi-part series, Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners first episode focused around the latest discoveries made by Professor Catherine Hall and her team at UCL. By using this database and following the claims, Olusoga begins to explain how the money was distributed, who received it and why such a large amount was needed.

What is uncovered is the modern equivalent of a £17 Billion compensation pay out was indeed given out by the British Government to more than 46,000 slave owners covering more than 800,000 slaves as stipulation for abolishing slavery in 1834.

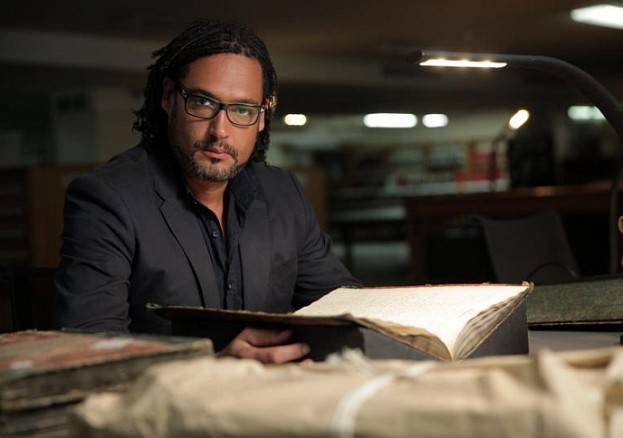

Much of the documentary focuses around the statistical data stored in the hundreds of inventory documents kept by both the 46,000 slave owners and the few hundred government workers who tracked the compensation claims in 1836, yet he does not fail to deliver and bring to life their stories set 200 years ago.

Unlike many other slave documentaries before it, Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners and Olusoga bring the harsh realities of slave life to light, not through dramatic reconstructions or interpretations, but through cold, hard facts such as through slave master diaries and carbon dated archaeological evidence. One such account is the ‘Barbados slave code’, a series of guidelines and enforcement protocols that were recommended to slave masters and plantation overseers in order to keep both compliant and unruly slaves in line.

What such documents and items reveal is more than just the exploitation of kidnaped Africans, the racist institutions which upheld slavery and the overwhelming wealth it generated, but also the constant regime of terror and life taking work all slaves would have endured from the moment they may have been kidnapped or born, till the moment they died.

The title ‘profit and loss’ responds to more than just the notion that the persons responsible for trading human lives generated massive amounts of wealth, but is also an indication to the social accolades, new responsibilities and even political power such wealth brought and bought too. This contrasts to the loss of humanity on both the side of the slaves, who were viewed as mere objects but also reflects the sheer barbarity many slave masters stooped to in their new climates trying to be live prosperous careers.

With such a focus, it can be argued that what the documentary does do, is help to directly address and dispel a number of claims that attempt to justify or even mask the true extent of slavery and its role in not only British society, but world history too.

Phrases such as ‘the slaves were treated rather well’ are directly juxtaposed with images of very heavy, Iron shackles with four or even five inch spikes protruding from the lock which would have cut the slave if they tried to run and first hand, accounts from slave overseer diaries. Within, David Olusoga recites overseers recounting their acts which may have been to rape, severely whip, stab or even cut a slave then fill their wounds with special mixtures of salt and other known irritants of the time to make the pain even worse.

It dismisses claims that if the slaves were treated so bad, they could have used their numbers to overpower the overseers and break free by recounting and reminding the audience that the sexual abuse many slaves endured and the psychological torture some experienced by being humiliated through physical punishment and torture such as by having animals defecate into their mouths- would have reduced the likelihood a slave would have been able to escape. Secondly, in the few cases a slave did escape, it was always another, larger societal figure that would have brought a slave back to their owner and if a slave did harm a white person; overseer or not, there was a likelihood they would be killed.

Other claims such as ‘only the rich ever had slaves’ are also dismissed too. Many claimants and compensation awardees were not only from the upper class, but were from the middle and lower middle classes too and each had a number of slaves which reflected their wealth.

However, the documentary is not a scathing attack on the people who owned slaves and historical context is not forgotten here. Towards the end of the documentary, Olusoga sheds some light into how women were treated and viewed in society.

With many being unable to work due to Britain’s restrictive laws, owning a slave meant that for some families, slavery was their main form of passive income and their only income once a husband died. It means that of the 46,000 claimants, 40% were female; sparking questions as to how many fatherless families would have coped once slavery came to an end and explains that for many, inheriting wealth- which would have often included a slave, was their only way of surviving against creditors, who too were profiting from slavery and it’s ventures.

However, what cannot be escaped is that slavery created and sustained dynasties for the British elite. In another scene, David Olusoga looks through a number of compensation claimants and follows the names of some families who were the original settlers in Barbados back in 1627. What he finds is that when he searches through the compensation claims that are awarded in 1836, the same surnames reappear and these are the names which you later see in and around London, Bristol and Liverpool investing their millions made from slaves into public projects such as building stately manors or investing into the £1bn West India Dock featured in East London, which is now sitting in the shadow of Canary Warf.

In the second episode, which is to air July 23rd, David Olusoga will bring to life the systematic and sustained propaganda war that was designed to undermine and hopefully derail the arguments against the abolition of Slavery.