By the end of the 17th century Parliament, with Royal support and backing, had supervised the development of a large and growing African population throughout English colonial possessions in the Americas.

The tentative efforts under Elizabeth I to break into the foreign monopolies on lucrative overseas trade whetted the appetite for more.

But it was the military and political turmoil in Europe in the early 17th century which allowed the English to establish their own trading systems to Africa and the Americas.

Above all, it was the pull of exotic commodities and riches which proved irresistible.

At first, Europeans were not drawn to Africa for slaves, although they did occasionally acquire them. The continent was more attractive to the early pioneering settlers for its valuable commodities – especially gold. The early trading companies focused on gold, dyes, timbers, ivory and hides.

What transformed everything was the development of colonies in the Americas.

The settlement of these and the Caribbean islands was to transform Europe’s dealings with Africa. The introduction of plantations, especially those growing sugar, led to the extensive use of African slave labour. In time some 70 per cent of all enslaved Africans shipped across the Atlantic were destined to work in the sugar fields.

Pioneered by the Spaniards and perfected by the Dutch, sugar plantations were eagerly adopted by the English from the 1620s. Sugar though was not the only crop. In the North American colonies the development of the tobacco industry – a crop acquired from local Indians – also led to the use of enslaved African labour.

Trading with Africa

Trading with Africa

The plantations in the Americas created a rush of traders to the African coast. Trade there expanded enormously and became a source of great European rivalry and strategic positioning.

The initial ad hoc ventures gave way to licensed companies, chartered and monitored from London.

A string of major trading posts were developed on the West African coast. The major forts and castles were designed more to protect gold and local officials, rather than to house enslaved Africans waiting for the slave ships.

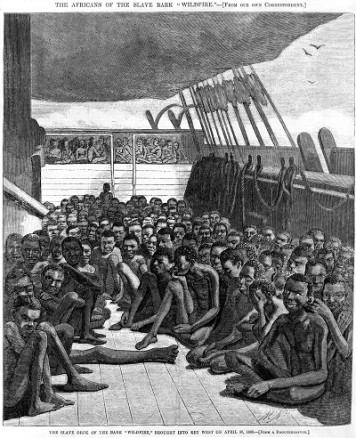

Most captured Africans were herded on board ships from beaches, from barracoons on the shore, from river stations, or were rowed out to the waiting vessels.

The Africa trade quickly emerged as a massive and lucrative form of international trade. By 1720 its most important branch was the dispatch of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic. But even that simple assertion does an injustice to its complexity.

The outbound slave ships to Africa were packed with British goods, such as metal goods, firearms, textiles and wines for exchange for human cargo. Vessels returning from the colonies heading to their home port were filled with plantation produce.

Here was a trading network on an integrated international scale, lubricated by slavery, and all approved, regulated and monitored by Parliament.

Dozens of Acts were passed specifically to encourage, regulate and monitor the trade in Africans.

Legislation relating to the more personal and private aspects of the slave trade, brought its consequences directly into the Parliamentary arena.

Parliament and commerce

In the years after the Restoration in 1660, the wider economic importance of the English sugar trade became more obvious. There were also international economic pressures.

On 8 April 1671, West Indian planters presented their arguments to the House of Lords for a stronger defence against their commercial and political rivals.

The City of London’s Corporation, the Bank of England, Lloyd’s insurance – and a host of banking facilities – all thrived on the Atlantic trades. So, too, did the industries which provided goods for exchange in Africa, equipped the slave plantations of the Americas, and processed and sold the imported slave grown produce.

Consumption rose and the number of shops increased, and exotic goods formed an important element in the growth of England’s finances. Duties and taxes raised by Parliament became critical sources of income. As a result, complex rules came to govern trade between England, Europe and the wider world.

Major ports and docks flourished in London, Bristol and Liverpool but the different levels of customs duties encouraged illicit imports which developed into a remarkable smuggling industry. To prevent such fiscal abuses, the state developed powers of scrutiny and punishment. Shopkeepers and tradesmen complained about such powers in petitions.

Sugar, tea and coffee

Sugar, tea and coffee

During the 17th and 18th centuries tobacco, but above all sugar, transformed British life. Britons developed their famous sweet tooth because their drinks – tea, coffee and chocolate, all naturally bitter – needed to be sweetened with sugar. They were also celebrated for the profusion of their puddings and desserts.

At the heart of this was slave-grown sugar. This led to a massive proliferation of shops across Britain, whose main source of income was goods from the West Indies

Parliament regulates the Africa trade

The growing trade with Africa soon came under the gaze of Parliament.

The Royal Africa Company’s monopoly in particular angered other merchants who wanted a share of the trade. The 1698 Trade with Africa Bill – which proposed that the company’s monopoly be broken – became an Act in the same year.

Many traders and merchants did not want regulation and duties applied to the Africa trade. They expressed themselves through pamphlets and petitions to Parliament. As the latter became involved in the regulation of the trade, it discovered a lot more about it.

Leading members of London’s black community

By the late 18th century the black population in London was in the thousands. Among them were Ignatius Sancho and Olaudah Equiano

Ignatius Sancho

Born on a slave ship, Ignatius Sancho (1729-80) was brought to England as a baby. He was educated in London and established himself in Westminster, buying a shop on Charles Street.

Sancho was an accepted and respected member of London’s intellectual and artistic society, and his life illustrated that Africans were equal in every way to the Europeans who enslaved them.

Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano (1745-97) was an active opponent of the slave trade. He lived and worked in London for several periods of his life. He was employed by the British government to work on the Sierra Leone settlement scheme, which was established to repatriate former enslaved Africans living in London.

Equiano was a leading member of the black community, working with Granville Sharp on legal cases involving Africans fighting to establish their rights to freedom in Britain. His autobiography was published in 1789.

Abolition: the argument

The movement against the slave trade had deep and slowly developing roots. Was slavery legal in England? Could slaves be removed from the country against their wishes? What was to be done about the maltreatment of black people?

Legal battles

All these questions and more surfaced in legal battles from the mid-18th century onwards. The Somerset case of 1772 ruled that slavery was illegal in England, calling into question the right of slave owners to hold jurisdiction over slaves brought to England.

In the Zong case of 1781 the owners of a British slave ship sought compensation for the loss of cargo, when over a hundred enslaved Africans were thrown overboard.

Both these landmark cases had been backed by the theologian, Granville Sharp, who became a key member of the abolitionist movement.

Defeat in North America

With the British defeat in the war in North America in 1783 slavery was set in a different context. Slavery had been at the heart of that conflict, and many of the defeated British came home with former slaves.

The problem of the black poor

There was also the problem of the black poor in London in the mid-1780s and discussion about what to do about them. This resulted in the Sierra Leone Scheme, designed with government backing to relocate them to Africa. It proved disastrous and gave focus to the issue of slavery and the slave trade.

Boycotting slave-grown sugar

The boycott of slave-grown sugar became an important feature of the abolition campaign. Refusing to buy sugar for the home, and preventing its domestic use, emerged as a contribution by women to the campaign.

The birth of the formal abolition campaign

At the time of these events a small band led by William Wilberforce in Parliament and by Thomas Clarkson in the country as a whole, launched the formal campaign to abolish the slave trade.

The abolitionists

William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce, MP for Hull from 1780, took up the cause of abolition after meeting a former slave trader, John Newton. Wilberforce would become the Parliamentary mouthpiece for the campaign.

Thomas Clarkson

Born in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, Clarkson was at Cambridge University preparing to become a clergyman when he entered and won the 1785 annual essay competition, the title set being ‘Is it lawful to enslave the unconsenting?’.

During his research he learned about, and was horrified by, the transatlantic slave trade. It was then that he decided that something should be done.

Within a year Clarkson had given up plans to enter the church and had decided to devote himself full time to the cause.

In 1787 Clarkson became one of the original 12 members of the London Committee, which also included Granville Sharp and was part of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

As the only Committee member without business commitments, Clarkson researched for evidence that could be laid before Parliament, and also promoted the cause nationwide.

He had earlier met many Quakers who were campaigning for abolition and when he travelled to all the major British ports, as well as cities and towns around Britain, Clarkson was supported by local Quaker groups.

His research was to prove crucial to William Wilberforce’s subsequent work in the House of Commons.

Petitioning Parliament

In 1788, a number of petitions in favour of the abolition of the slave trade were received by Parliament.

However, the powerful federation of planters, merchants, manufacturers and ship owners – all central to the slave trade – put up a dogged rearguard action against abolition in both the Commons and Lords.

Both sides presented petitions to both Houses of Parliament.

Those petitioning against the trade were encouraged by Thomas Clarkson. One of the purposes of Clarkson’s tours of Britain between 1788 and 1794 was to organise and encourage a new public petitioning campaign.

Both sides were using a means of communicating with Parliament that had a long history, but was now on a scale not seen before.

The petitions show that a time when the right to vote was very restricted, the petitioning movement gave many excluded from the electoral process an opportunity to communicate with Parliament

The first parliamentary debates

The MP for Hull, William Wilberforce, had met the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade and, with the encouragement of William Pitt, the Prime Minister, agreed to raise their cause in Parliament.

In February 1788 the prime minister commissioned a report on the slave trade and the effects and consequences for British commerce. The report was undertaken by the Privy Council committee for trade and foreign plantations.

This was followed by a statement in the Commons by William Pitt on 5 May 1788. He said that he would raise the issue by moving a motion “That this House will, early in the next session of Parliament, proceed to take into consideration the circumstances of the Slave Trade”.

Following a debate, which revealed divided opinion, the motion was agreed. During the debate, the MP for Oxford University, Sir William Dolben, suggested that some limited regulation should take place.

Dolben introduced a Bill on 21 May to regulate the numbers of enslaved Africans carried from Africa to the West Indies.

The Bill received Pitt’s support, providing that the measure was temporary pending discussion in the next session. Dolben’s Bill was passed after a series of debates, receiving Royal Assent in July 1788.

Thomas Clarkson, a member of the London Committee of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, drew up a plan of the Brooks slave ship, graphically illustrating the 16 inches (40cm) allocated to each person.

This plan was sent to every member of the Commons and Lords by the London Committee, who were lobbying for further debate. It was also distributed around the country where it had an immediate impact.

Wilberforce makes the case

The movement to abolish the slave trade drew on a remarkably wide range of activities, including collecting signatures on petitions, female activism, and distribution of print and graphic images.

It was, however, at its heart, a parliamentary campaign, headed by William Wilberforce. A measure of his success was the fact that by 1792 abolition was an issue entrenched in Parliament. However, it faced a protracted and difficult struggle.

Wilberforce was not formally involved until he was asked by his close friend, the newly-elected Prime Minister, William Pitt, to become the parliamentary spokesman for the campaign in 1787.

The London Committee, part of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, made occasional contact with Wilberforce from October 1787, mainly to ask him to raise the issue in debates.

He formally joined the Committee in 1791 and became their spokesman in the House of Commons.

Pitt set up an enquiry into the slave trade in 1788, and laid its report before the Commons in April 1789.

The following month, Wilberforce pushed for a committee to consider the anti-slave trade petitions that had been presented to the House. He made a long speech emphasising the harsh realities of the slave trade.

Although it was eventually decided to postpone more discussion until the following parliamentary session, Wilberforce had done enough to secure the appointment of a select committee to consider the matter further.

The evidence

Perhaps the most decisive and influential blow against the slave trade was the evidence presented to various enquiries from men who knew the slave ships and plantations at first hand.

What these committee reports told of African suffering had a profound impact. They produced revulsion in those who read them and helped to win over armies of supporters to the abolitionists’ side.

The enquiry set up by Pitt produced a 900-page report and detailed the evidence of abolitionist Thomas Clarkson.

In one particular example, Thomas Clarkson’s argument that Africa had many goods worthy of trade was corroborated by fustian manufacturer John Hilton. Hilton had looked at a sample of cotton wool from Senegal, collected by Clarkson, and rated it highly.

Olaudah Equiano also expressed support for trade with Africa and wrote a letter to the Privy Council committee carrying out the enquiry.

Other evidence heard by subsequent committees was contradictory. Two witnesses gave evidence describing slave ships. Captain John Knox said that he had no knowledge of the kidnapping of slaves or obtaining slaves by fraud or oppression, whereas James Towne spoke of slaves shackled on overcrowded ships.

Drive for abolition slowed by external events

Despite the pressures for change which built up between 1788 and 1791 the abolitionist cause was not yet won.

Two events were responsible. The first was the French Revolution, which became ever more extreme. The second was the massive slave uprising in St. Domingue, a French colony in the West Indies, led by Toussaint-L’Ouverture.

A series of revolts began on the island shortly after news reached it of the start of the revolution in France in 1789. The British attempt to seize the colony proved a disaster, with the loss of more than 40,000 British lives.

All this served to halt the drive for abolition, which did not pick up momentum again until after the death of William Pitt in 1806, and the emergence of a more sympathetic government under Lord Grenville.

There had been a string of parliamentary regulations tightening the conduct of the slave trade, but the final abolition had to wait until 1807. Despite this, the 1790s saw repeated attempts by William Wilberforce to keep the issue in the public arena.

Parliament abolishes the slave trade

In 1805 an abolition bill failed in Parliament, for the eleventh time in 15 years. The London Committee decided to renew pressure, and Thomas Clarkson was sent on a tour of the committees nationwide to rally support for a second petitioning campaign.

The Foreign Slave Trade Abolition Bill of 1806 became a focus for these petitions. The Bill, which would prevent the import of slaves by British traders into territories belonging to foreign powers, was introduced – as a government measure – by the Attorney-General, Sir Arthur Leary Piggott.

The abolitionists inside Parliament, led by Wilberforce, seemed to pay it little attention, and it passed its early readings without much notice. However, by the third reading, the anti-abolitionists understood its broad implications and that Wilberforce and his colleagues had implemented a clever strategy to play down its wider ramifications.

The Bill was passed on 23 May 1806 and the stage was set for full abolition of the British trade. The Prime Minister, Lord Grenville, introduced the Slave Trade Abolition Bill in the House of Lords on 2 January 1807 for its first reading.

Its introduction by the head of the Government marked it as official policy, and its second reading in the Lords was agreed 100 votes to 34, despite resistance from the Duke of Clarence (the future king William IV) and other peers with West Indian interests. After consideration by committee and a third reading, the Bill arrived in the House of Commons on 10 February.

The London Committee members rented a house in Downing Street to be close to Parliament to lobby MPs. After 18 years of promoting abolition Wilberforce received a standing ovation during the key Commons debate on 23 February. The debate lasted ten hours and the House voted in favour of the Bill by 283 votes to 16 – a victory far in excess of expectations.

The remaining stages took a further month, and the Bill received Royal Assent on 25 March 1807.

What happened next

Although the British ended their slave trade in 1807, slavery itself continued in the British colonies until full emancipation in 1833. An illicit slave trade continued across the Atlantic, and more than a million Africans were landed in the Americas (mainly Cuba and Brazil) after 1807.

Historians remain puzzled by the abolition of the slave trade. Was it ended because it was no longer profitable? The economic data, and the tenacious support of the slave traders, suggest not. But is it plausible to see abolition being brought about by outraged sensibility or religious sentiment? If it was wrong or un-Christian in 1807, why not in 1707?

What exactly changed in Britain and the Atlantic world – and indeed in Parliament – in the years between 1600 and 1807? There seems to have been a shifting of the tectonic plates; a small series of movements which produced massive consequences.

Read House of Commons Historic Hansard for debates from 1803-2005