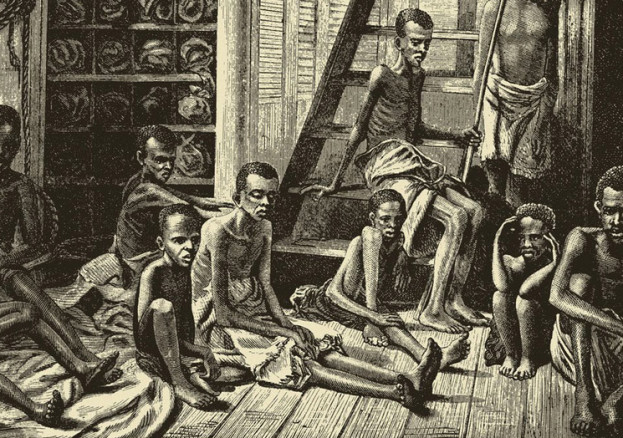

Conditions on board ship during the Middle Passage were appalling. The men were packed together below deck and were secured by leg irons. The space was so cramped they were forced to crouch or lie down. Women and children were kept in separate quarters, sometimes on deck, allowing them limited freedom of movement, but this also exposed them to violence and sexual abuse from the crew.

The air in the hold was foul and putrid. Seasickness was common and the heat was oppressive. The lack of sanitation and suffocating conditions meant there was a constant threat of disease. Epidemics of fever, dysentery (the ‘flux’) and smallpox were frequent. Captives endured these conditions for about two months, sometimes longer.

In good weather the captives were brought on deck in midmorning and forced to exercise. They were fed twice a day and those refusing to eat were force-fed. Those who died were thrown overboard.

The combination of disease, inadequate food, rebellion and punishment took a heavy toll on captives and crew alike. Surviving records suggest that until the 1750s one in five Africans on board ship died.

Some European governments, such as the British and French, introduced laws to control conditions on board. They reduced the numbers of people allowed on board and required a surgeon to be carried. The principal reason for taking action was concern for the crew and not the captives.

The surgeons, though often unqualified, were paid head-money to keep captives alive. By about 1800 records show that the number of Africans who died had declined to about one in eighteen.