The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act (1807) gave the Church an opportunity to address the controversial and painful truth that whilst a number of Christians, both Black and White, mobilised the first mass human rights movement to bring about abolition of the transatlantic slave trade, many of their Christian brothers and sisters were committed to maintaining the trade in enslaved Africans.

Most Christian denominations supported the slave trade. Some, such as the Quakers and the Church of England, held slaves at some point during the 17th and 18th centuries. In general, British planters opposed the idea that their slaves should be exposed to Christianity because they feared instruction in the English language would allow their African chattel to plot sedition and create unrest. Nonetheless, a number of enslaved Africans did learn to read and write and demonstrated that they were capable of organising themselves in the struggle for their own freedom.

Emancipation and insurrection

For enslaved Africans the struggle for freedom began at the very moment of their capture. Many threw themselves overboard from the ships transporting them to a strange land. Upon arrival in the Americas they sought countless ways to escape rather than remain bound in chains, flogged as common criminals or branded like animals to work until they literally dropped or died. These were a proud people who came from their own forms of civilisation but now found their lives sacrificed to a system that stripped them of their dignity and abused their humanity. In essence, the transatlantic slave trade was a barbarous mechanism by which a mostly Christian, overwhelmingly European plantocracy ‘created’ wealth.

Rebellion formed an endemic feature of chattel slavery during the three centuries the institution endured in the colonies. Even before setting sail, Africans were reported to have blown up the slave ship Le Couleur on the Coast of Guinea (York Herald, 31 March 1792). In the West Indies plotting, rioting, and running away were just three ways in which enslaved Africans challenged their condition. A group known as the Maroons resisted British efforts to dislodge them from their mountain hideout in Jamaica. They remained an uncontrolled threat to plantations until they won their freedom from Britain.

Religious meetings were the only gatherings allowed for slaves and Sam Sharpe used these gatherings to share his vision of freedom with his fellow slaves. Sam Sharpe was a respected Baptist Deacon in Jamaica. He took very seriously the teachings of the Bible that all are equal in the sight of God and believed he was equal to his master. Sharpe travelled around the island preaching against the inhumane treatment meted out to slaves but in gathering support for his movement he insisted on non-violent action. He encouraged enslaved Africans to stop work unless they were paid for their labour. A few among them were unable to suppress their anger and, despite Sharpe’s plea, the action turned violent. Over £1 million worth of damage was done to property; 200 Africans and 15 White men were killed. Sharpe was captured and just before his execution said, ‘I would rather die than live in slavery.’ After his death, Sam’s owners were paid 16 pounds and 10 shillings as compensation for their ‘lost property’.

Freedom writers

Violence was not always used as a means of emancipation. In the 18th century a number of Africans used intellectual means to promote the message of abolition. One such African was Olaudah Equiano who learned to read and write as a way of improving himself and charting a way out of slavery. In 1759 he arrived in London and in 1789 he published his autobiography: The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Equiano used his book as a campaigning tool as he travelled around Britain seeking immediate abolition. He worked alongside the English abolitionists, petitioning Parliament against what he described as ‘unchristian behaviour.’ Knowing George III and his son were very firmly in the pro-slavery camp, Equiano wrote a letter to Queen Charlotte appealing to her sympathetic nature.

Equiano’s contemporaries also used their writing skills to advance the abolitionist agenda. With help from Equiano, in 1787 Ottobah Cugoano published: Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species. By now these Black abolitionists, fully conversant with the Bible, demolished the pro-slavery claims that ‘slavery had divine sanction’ and ‘Africans were by nature suited to slavery.’

Black women also added their contributions to the abolition movement by means of their writing. Phyllis Wheatley was captured from Senegal c1753 at the age of eight and sold to a wealthy family in Boston, Massachusetts. She had an aptitude for learning languages and was encouraged by her more humane owners to develop her writing skills. In London she published a collection of poems. Mary Prince was assisted to write about her painful experiences to spread the anti-slavery message in a way that appealed to women, many of whom later organised anti-slavery societies throughout Britain.

Resistance and freedom

Slaves in British colonies were encouraged in their acts of resistance when enslaved Africans in the French colony took control of a large part of the island of Saint Domingue. At a time when the Napoleonic wars were being fought out in the Caribbean Seas, French planters offered the island of Saint Domingue (Haiti) to England in 1791 and fierce battles raged between the two states for this prize which became known as the world’s sugar bowl because it was the largest sugar producer in the 18th century.

This was also a time when Tom Paine’s ideology of liberation and equality travelled across the seas from the Sans Culottes in Paris to the American war and to this small island. Revolution was surely in the air when Toussaint L’Ouverture, a former slave, led an army of enslaved Africans to defeat both the French and British and helped to establish the first Black republic. In August 1793 L’Ouverture decreed the liberation of slaves and France had no alternative but to endorse this formally by freeing all slaves in its empire. The Saint Domingue revolution was the most significant action by 18th century Black abolitionists with some 50,000 French soldiers killed, more than at Waterloo. L’Ouverture was later captured and imprisoned.

The pro-slavery lobby

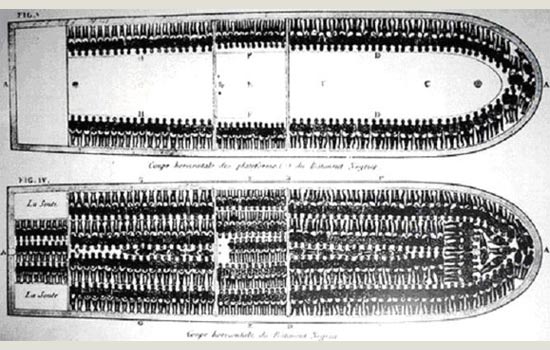

The pro-slavery lobby in Britain included merchants, shipbuilders, financiers and plantation owners, known as the West India Committee. Pro-slavers including Robert Norris, Lord Rodney and Sir Peter Parker told The Privy Council that ‘slaves had sufficient room and provision on board ships, they were well fed and clothed, and amused themselves with dancing.’

Fortunately, Equiano was able to expose these accounts as nothing more than lies. From personal experience he was able to describe conditions on board slave ships as ‘a multitude of Black people of every description chained together, every one of their countenances expressing dejection and sorrow.’

Clearly, merchants had the ears of a great many Parliamentarians in the House of Commons such as Colonel Banastre Tarleton (MP for Liverpool) and the Duke of Clarence (son of George III). A significant number of Bishops in the House of Lords were among those in favour of maintaining the slave-owning plantation system. They argued that any move to abolish the trade would result in planters being ruined or massacred. Their interest was substantial. When slavery was finally abolished in 1833, the Bishop of Exeter received £12,700 in compensation for his 655 slaves.

The strength of the pro-slavery lobby ensured that when William Wilberforce (MP for Hull) tabled his abolitionist Bills in 1789 and 1791 they were soundly defeated in both the House of Commons and the House of Lords. An amendment Bill finally succeeded in 1792 calling for a gradual end to the slave trade.

Champions

It took 15 years before Parliament finally prohibited the carrying of slaves in any British ship and even then there were dissenters. The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed on 25 March 1807, having been approved by the House of Lords (by 100 to 34) and the House of Commons (by 283 votes to 16). Even then, enslaved Africans still had to wait a further 30 years to achieve full emancipation throughout the British Empire. Nevertheless, the 1807 result was a turning point. By that time a grand coalition of assorted Christian abolitionists – Black and White; female and male; those pursuing political means; those advocating non-violent resistance; and those leading armed rebellion – had emerged as champions.