The speech combined old fashioned racism (‘wide grinning piccaninnies’) with new forms of racism against those from a different culture, calling for stricter immigration controls on these apparent alien elements (‘numbers are of the essence’). And while Powell complained that his arguments were silenced, his speech was given the upmost media attention, his words amplified and reverberating across the country. ‘Send them back’ became a phrase now given respectable legitimacy, and a tidal wave of racist attacks emerged out of the supposedly refined remarks from the Conservative politician.

This year the shadow of Enoch Powell has been cast over political debate in Britain once again. At the height of the Windrush scandal the BBC decided to mark the 50th anniversary of ‘Rivers of Blood’ with the first broadcast of the speech in full. Meanwhile in Wolverhampton a debate emerged earlier this year after a proposal was submitted for a blue plaque to mark Powell’s service to the city. Supporters of the plaque suggested that Powell was a harmless and intriguing contribution to the heritage of Wolverhampton; he had, after all, served as MP for Wolverhampton South West for 24 years. Less coded remarks in support of the plaque illuminated the centrality of Powell as a cornerstone of far right ideology. A plaque for Powell served then as a sort of shrine for his twenty first century followers. Thankfully, however, a campaign against the plaque proposal was launched by local anti-racists and was able to draw in a range of voices including all three Labour MPs, the Bishop of Wolverhampton as well as trade unionists and local academics. Finally, and under pressure from anti-racist campaigners, the local Civic and Historical Society announced that they would not be proceeding with any plaque for Powell.

This year has been not just the anniversary of Powell’s speech, but has also marked 25 years since the racist murder of Stephen Lawrence. Despite the decades apart, Powell’s words were still able to weave into the actions of the murder. In the BBC documentary this year, it showed secret film footage of Stephen Lawrence’s suspect murderers. In the comfort of their own home, they were filmed extolling the great Enoch Powell. Powell’s eminence as an establishment politician alongside his academic and military credentials, clearly continued to providence an ideological anchor to far right violence, pushing forward and giving confidence to what Paul Gilroy has described as ‘free-lance implementers’ of Powell’s words. The history of Powell and his most infamous speech cannot be blocked out or forgotten then. Powell’s memory is persistently returned to by a wide range of powerful voices professing varying degrees of attachment to his politics. Instead of ignoring this reality, we need to directly confront the racism of the past and reflect on how this history has shaped where we are today.

My book is about Enoch Powell’s most infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech but particularly it is concerned with how the speech impacted on black and Asian people within Powell’s constituency in the industrial town of Wolverhampton. I look particularly at how these new forms of racism influenced not only the public protests and street attacks, but also everyday experiences within the schools and the workplaces. Those who suffered from the words of their MP were not, however, passive victims. Anti-racist resistance also came to the fore in this period, pushed on by the reconfiguration of racist politics in Britain. Rather than a blue plaque for the MP who attempted to divide and rule his constituency, in a desperate bid to lead his party and the country, we should remember all those who stood up to the racism unleashed. They were, in 1968, sometimes in a minority in their workplaces and neighbourhoods, but their determination laid important roots for a mass anti-racist movement which would develop in the late 1970s. Black and Asian people were forced by people like Powell to fight for their rights in Britain with their very belonging in Britain challenged by those at the top. Rights were never given passively, but were won by struggle from below and in my book I try to draw out some of the stories of local people who fought against Powell’s nightmare vision. 50 years on and it might be worth returning to this history to think through the lessons of how we fight racism and the ‘hostile environment’ today.

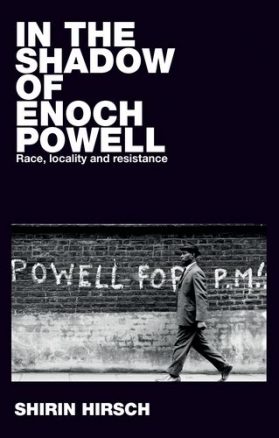

In the Shadow of Enoch Powell: Race, locality and resistance by Dr Shirin Hirsch is out next month