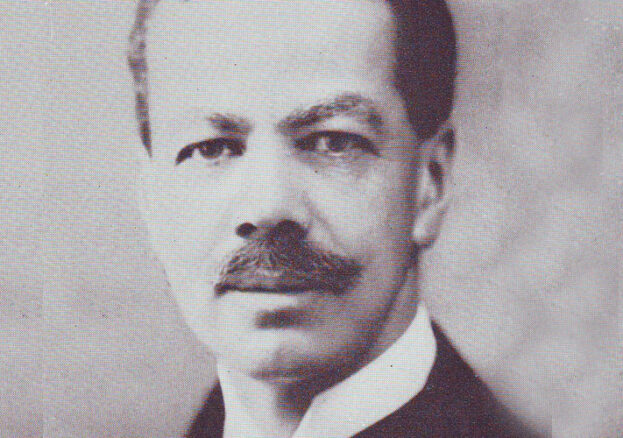

Born in Demerara, British Guiana (now Guyana), Russell’s father, William Russell, was a wealthy sugar plantation owner and mechanical engineer born in Scotland, apart from being of African descent very little is known of Russell’s mother.

Russell was privately educated in Scotland, at Dollar Institution in Clackmannanshire from 1880-1882 before studying medicine and surgery at Edinburgh University between 1882 – 1886.

He was an exceptional scholar and his Edinburgh Doctorate of Medicine was awarded the gold medal for outstanding achievement in 1893.

With the support of his mentor, Sir Victor Horsley, founder of British neurosurgery, Russell was appointed senior house physician at the National Hospital – a pioneering specialist neurological hospital – in 1888. By 1903 Russel had been appointed to the hospital’s management board.

Russell threw himself into his work publishing more than 15 research articles between the 1890s and 1908, advancing the knowledge of both neuroanatomy and cerebellar physiology. Around 1900 he was appointed professor at University College, London, and, after 1907, he served as vice president, and also president of the neurology section of the Royal Society of Medicine. From 1902 until his death 44 Wimpole Street was Russell’s family home and place of work, its location afforded Russell the opportunity to be at the centre of London’s medical community.

His opinions were not always popular with his fellow professionals and his belief that patients suffering from psychosis were too often committed to asylums when they could be better cared for within their families, assisted by general practitioners, was criticised by psychiatrists at the time.

From 1908 until 1918 Russell served as a captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), working at the 3rd London General Hospital which used to treat soldiers returning from the First World War who needed specialist treatment, such as those with shellshock.

His commission as an officer was unusual as the War Office was known to be hostile to Black doctors, including those trained at British universities. It advised that only West Indian medics of ‘pure European descent’ were likely to be accepted as officers in the RAMC.

After the war, Russell continued to campaign for reforms to lunacy laws and to keep patients with less severe mental health issues out of mental institutions, becoming the Chairman of the National Society for Lunacy Reform in 1924. Russell left his work at the National Hospital in 1930.

He continued his private practice from Wimpole Street but died suddenly aged 75 in March 1939, he was buried in Highgate Cemetery. In 2021 a blue plaque was placed at 44 Wimpole Street in commemoration of Russell’s life and work.

As the nation’s largest Armed Forces charity, the Royal British Legion (RBL) is dedicated to ensuring that all those who served and sacrificed, and who continue to do so, in defence of our freedoms and way of life, from both Britain and the Commonwealth, are remembered.

In our acts of Remembrance, the RBL remembers,

- The sacrifice of the Armed Forces community from Britain and the Commonwealth.

- Pays tribute to the special contribution of families and of the emergency services.

- Acknowledges the innocent civilians who have lost their lives in conflict and acts of terrorism.

The story of Black British and Black African and Caribbean service and sacrifice is one that we are keen to share, a story of men and women who have done so much in defence of Britain and in protecting all our citizens. A story that is replete with stories of bravery and courage, as epitomised by Victoria Cross winner Johnson Beharry.

Therefore, to mark 100 years since Britain’s current Remembrance traditions first came together, the RBL has bought together over 100 stories of British and Commonwealth African and Caribbean service and sacrifice. The stories range from the First World War to the present day and are of servicemen and women from across Britain, Africa and the Caribbean, representing both the armed forces and emergency services.

Therefore, to mark 100 years since Britain’s current Remembrance traditions first came together, the RBL has bought together over 100 stories of British and Commonwealth African and Caribbean service and sacrifice. The stories range from the First World War to the present day and are of servicemen and women from across Britain, Africa and the Caribbean, representing both the armed forces and emergency services.

The RBL wishes to offer special thanks to Stephen Bourne for his help in putting these stories together. Stephen Bourne has been writing Black British history books for thirty years. For Aunt Esther’s Story (1991) he received the Raymond Williams Prize for Community Publishing. His best-known books are Black Poppies (2019) and Under Fire (2020). His latest book Deep Are the Roots – Trailblazers Who Changed Black British Theatre was recently published by The History Press. For further information about Stephen and his books, go to his website www.stephenbourne.co.uk