At the end of the war, Charles remained in Liverpool where the Black community had grown to 5,000 strong as a result of the recruitment of Black people from within the British Empire to work in industries such as chemicals, sugar refining and munitions in order to fill the labour shortage created when white British workers enlisted in the armed forces.

However, following widespread demobilisation at the end of the First World War tensions began to mount as black workers and ex-servicemen competed with white ex-servicemen for work. The situation worsened when 120 Black workers employed in the sugar refineries and oilcake mills were sacked because white workers refused to work alongside them.

As a result, many black workers were evicted from their lodgings and joined hundreds of destitute black ex-servicemen. The Colonial Office was petitioned to repatriate the men with a 5 shillings bursary for food, clothing and tools. While a deputation representing 5,000 jobless white ex-servicemen complained that they were being undercut by the wages that black workers were being paid.

The situation exploded on 4 June 1919 when a West Indian, John Johnson, was brutally stabbed in by two Scandinavian sailors after refusing to give them a cigarette in a pub. The following night Johnson’s friends went back to the pub in retaliation. During the fight, a policeman was kicked unconscious. The police raided a row of hostels and other houses occupied by the Black community in response. Four officers were injured in the raids and in response, an enraged mob gathered outside the properties.

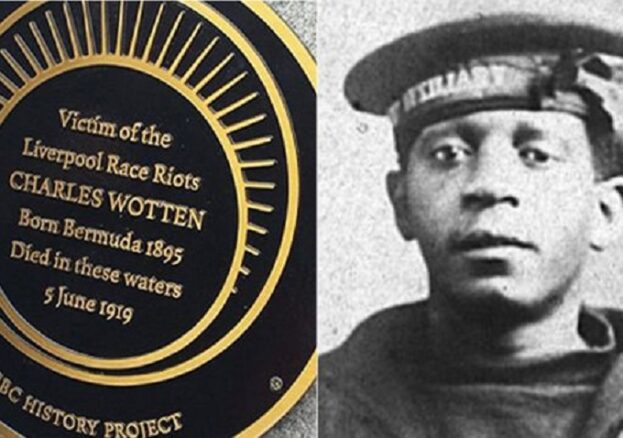

Charles who had no involvement in the fighting ran out and was pursued by two policemen and a crowd of around 300. Charles was chased to the Queen’s Dock where the mob began to throw bricks and stones at him, forcing Charles to throw himself into the water. A detective climbed down a rope to try and pull Charles out of the water but as he did so a stone was thrown from the crowd which struck Charles in the head. Charles sank and died; his battered corpse was only recovered later.

Despite several police officers being present no arrests were made for the murder of Charles. The Police raids continued and eleven Back men, one in naval uniform and several with bandaged heads were charged with virtually no evidence of attempted murder. As a result of the charges, a white mob of approximately 10,000 people spent the following three days attacking any Black people they saw in Liverpool.

Black workers were also fired by their employers during the riots and Arab and Chinese homes and businesses were attacked and set ablaze, often with no recompense for the victims from the government. While anti-Black riots also took place in Glasgow, London and Salford none were of the scale of those in Liverpool. In the wake of the riots, the British government intensified a repatriation scheme and between 1919 and 1921 an estimated 3,000 black and Arab seamen and their families were removed from Britain. In May 2016, a BBC commemorative plaque was dedicated to Charles at the site of his death.

As the nation’s largest Armed Forces charity, the Royal British Legion (RBL) is dedicated to ensuring that all those who served and sacrificed, and who continue to do so, in defence of our freedoms and way of life, from both Britain and the Commonwealth, are remembered.

In our acts of Remembrance, the RBL remembers,

- The sacrifice of the Armed Forces community from Britain and the Commonwealth.

- Pays tribute to the special contribution of families and of the emergency services.

- Acknowledges the innocent civilians who have lost their lives in conflict and acts of terrorism.

The story of Black British and Black African and Caribbean service and sacrifice is one that we are keen to share, a story of men and women who have done so much in defence of Britain and in protecting all our citizens. A story that is replete with stories of bravery and courage, as epitomised by Victoria Cross winner Johnson Beharry.

Therefore, to mark 100 years since Britain’s current Remembrance traditions first came together, the RBL has bought together over 100 stories of British and Commonwealth African and Caribbean service and sacrifice. The stories range from the First World War to the present day and are of servicemen and women from across Britain, Africa and the Caribbean, representing both the armed forces and emergency services.

Therefore, to mark 100 years since Britain’s current Remembrance traditions first came together, the RBL has bought together over 100 stories of British and Commonwealth African and Caribbean service and sacrifice. The stories range from the First World War to the present day and are of servicemen and women from across Britain, Africa and the Caribbean, representing both the armed forces and emergency services.

The RBL wishes to offer special thanks to Stephen Bourne for his help in putting these stories together. Stephen Bourne has been writing Black British history books for thirty years. For Aunt Esther’s Story (1991) he received the Raymond Williams Prize for Community Publishing. His best-known books are Black Poppies (2019) and Under Fire (2020). His latest book Deep Are the Roots – Trailblazers Who Changed Black British Theatre was recently published by The History Press. For further information about Stephen and his books, go to his website www.stephenbourne.co.uk