Black British life has been sorely underrepresented in our national cinema, but there have been hints of a resurgence in recent years. Amma Asante’s 18th-century-set drama Belle (2013) became an international box-office success, shining a light on the true story of Dido Elizabeth Belle, the mixed-race daughter of an African woman and a British naval captain; Destiny Ekaragha’s Peckham-set comedy Gone Too Far! (2014) sharply observed the tensions between young Britons of Jamaican and Nigerian descent; and Debbie Tucker Green’s magnificent Second Coming (2014), starring Idris Elba and Nadine Marshall, skilfully examined an unexpected, mysterious pregnancy and its resultant impact.

More recently, two key films arrived courtesy of young Nigerian-British talents: Shola Amoo’s beguiling, unusual docudrama A Moving Image (2016) looks at the impact of gentrification on Brixton, and Joseph Adesunloye’s moving White Colour Black (2016) follows a young London photographer on his journey to Senegal to bury his estranged father. Meanwhile, Asante followed up Belle with the period romantic drama A United Kingdom (2016), starring David Oyelowo as Prince Seretse Khama of Botswana. Away from the cinema, Steve McQueen has developed a major BBC television series that will follow a group of black British friends and their families over a number of decades.

So, there’s plenty to look forward to. But what about looking back? Following a number of issue-based films that addressed the black British experience in the 1950s and 60s (Pool of London, Sapphire, Flame in the Streets), the first wave of films to genuinely focus on a new generation of postwar, Windrush-era arrivals and their children in Britain began in 1975 with the release of Horace Ové’s brilliant Pressure.

The 1980s saw a surge in activity for black British production and representation, encouraged in part by the arrival of Channel 4 (which put diverse programming at the centre of its remit) in 1982. Since then, due to a combination of factors (lack of training and funding, exodus of talent to the United States), there’s been a cycle of frustration in maintaining and developing the black British presence on film. While a significant breakthrough in its own right, for a long time Ngozi Onwurah’s 1995 Welcome II the Terrordome stood as the only film by a black British woman ever to see UK release.

Even so, a significant – if under-seen and underrated – body of work exists that’s dedicated to exploring black British life in all its complexity, diversity, sadness and joy. Here are 10 of the best.

Jemima + Johnny (1966)

Directed by South African Lionel Ngakane – an ANC member exiled to London – this touching, half-hour long film is a masterclass in brisk, fluid storytelling.

Five-year-old Johnny, the white son of a right-wing nationalist father (who is shown demonstrating against immigration) strikes up an instant, close friendship with Jemima, the daughter of a recent West Indian immigrant family; her community is depicted with refreshing detail and sensitivity. The children’s friendship symbolically flies in the face of bigotry and London’s de facto segregation patterns of the era. Ngakane’s clear-eyed optimism for a colour-blind society is hugely touching, yet also sad when viewed in the light of the subsequent failure of this utopian ideal to materialise.

Ngakane was a pioneer, but he wasn’t the only filmmaker depicting black British life in the 1960s: Jamaican actor-turned-director Lloyd Reckord made the experimental short Ten Bob in Winter (1963), about the exchange of a 10-shilling note between two Caribbean immigrants of different classes; and in 1969 Frankie Dymon made the wacky, experimental Death May Be Your Santa Claus (available as an extra on the BFI Flipside Blu-ray of Joanna.)

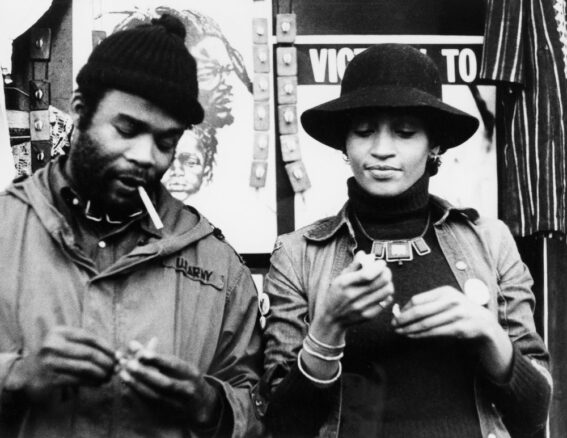

Pressure (1975)

Widely regarded as the first black British feature film, Horace Ové’s gripping, neorealism-inspired drama focuses on the tribulations of school grad Tony (Herbert Norville), the British-born son of first generation Trinidadian immigrant parents who arrived in England in the 1950s.

Facing the myriad pressures cited in the film’s reggae title track (parental, social, mental, ‘Babylon’ aka the police), the befuddled Tony floats through Ové’s film like a slow-motion pinball. He can’t get hired (he’s either shut out by racist employers or overqualified for menial labour); his potential romance with a friendly white girl is kiboshed by a hostile landlady; he’s ill-suited to the life of petty crime preferred by the group of ne’er-do-wells he falls in with; and his parents are stuck in their old ways.

Tony gets the most aggro from his elder brother Colin (Oscar James), a Black Power advocate. Colin laments his failure to “get him [Tony] to think black”, unable to grasp that Tony’s experience as a young black man born in Britain is different to his own. “You’ve got somewhere to go back to,” Tony tells Colin, “You have the dream of sun, sea and palm trees. What have I got? Office blocks!” Pressure is more observational and vérité-like than plot-driven, but conflict arises when Tony must decide whether or not to get involved in the Black Power cause. Pressure makes a good companion piece with Anthony Simmons’ comedy-drama Black Joy (1977), which deserves a place in this list too.

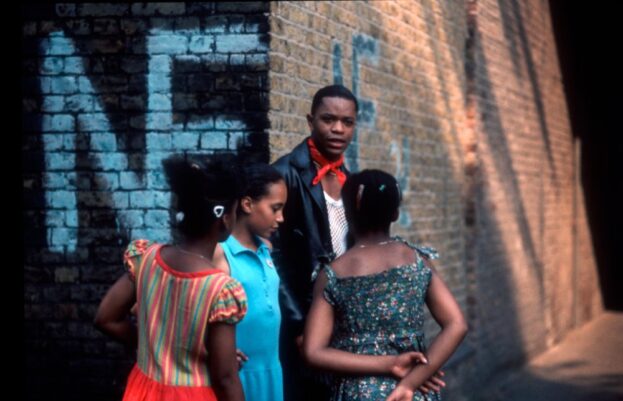

Babylon (1980)

As an editor on Horace Ové’s classic concert documentary Reggae (1971), and the director of BBC’s Linton Kwesi Johnson documentary Dread Beat an’ Blood (1978), Franco Rosso was an apt choice to helm the first major British feature film to take reggae music as its central theme.

Set predominantly in south London’s black community, Babylon is a gritty, episodic study of the external and internal pressures that compel frustrated car mechanic and aspiring reggae artist Blue (Aswad guitarist-singer Brinsley Forde) into committing an act of catastrophic violence.

Boasting a strong sense of place and a cast of superb young black British actors (plus future Flash commercials heartthrob Karl Howman), Babylon balances a complex appreciation of themes like racism, Rastafarianism and black identity with a satisfyingly gripping narrative. Babylon is also notable for its sheer stylistic brio, thanks in large part to the piercing, dreamlike cinematography by Chris Menges (Kes, 1969; The Killing Fields, 1984).

Burning an Illusion (1981)

The debut feature by Barbados-born Brit Menelik Shabazz focuses on west Londoner Pat (Cassie McFarlane), a young, independent black woman making a living against the volatile backdrop of Margaret Thatcher’s Britain: a time of discriminatory stop and search laws, and bubbling social anomie which resulted in riots across the UK, including in Brixton and Toxteth. The film’s key focus, though, is Pat’s journey to political ascension, via the ups and downs of her relationship with mercurial manual labourer Del (Victor Romero-Evans).

Burning an Illusion is notable for its rounded characterisation. Pat is a compelling lead: a complex female character with competing desires, the likes of whom is rarely portrayed in British cinema. The film is further marked by some terrific location shooting: we’re immersed in a variety of evocative London locations like the Notting Hill carnival, a crucial event in black British culture. Shabazz went on to make a number of plays and documentaries; his most recent work is music doc The Story of Lovers Rock (2011).

Playing Away (1986)

Ové’s second fiction feature uses cricket – a sport with a complex colonial history – as a launchpad for a smart, sly and sharply observed comedy of cultural manners.

Playing Away begins in mid-80s Brixton, a world away from its current hyper-gentrified state, where a group of West Indian friends (including future Desmond’s stars Norman Beaton and Ram John Holder) attempt to organise themselves ahead of a forthcoming trip. They eventually get their act together, and head to the fictional, leafy suburb of Seddington to play a team comprised of poshos and local oiks (among them future Grant Mitchell, Ross Kemp) in a rather patronising charity game in support of their “Third World Week”. Sparks, opinions, revelations – and a few nifty leg-breaks – duly fly.

Young Soul Rebels (1991)

As the founder of the Sankofa artists’ collective, Isaac Julien was long established as a key figure in the British culture scene by the time of this exciting 1991 film.

Set in 1977, during the week of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee, Young Soul Rebels focuses on a murder investigation involving one of the central characters, Chris (Valentine Nonyela), and his relationship with his girlfriend (Sophie Okonedo). The parallel narrative involves the romantic relationship between Chris’ friend, soul boy Caz (Mo Sesay), and a white punk (Jason Durr). They face the double prejudice of racism and homophobia, in both West Indian and white British communities.

This entertaining stew of sexual, racial and social identity in a changing Britain is notable for launching the career of future Academy Award nominee Okonedo. With music by the O’Jays, the Blackbyrds, Parliament-Funkadelic, War and Roy Ayers (among others), Young Soul Rebels also boasts one of the best soundtracks in British cinema history.

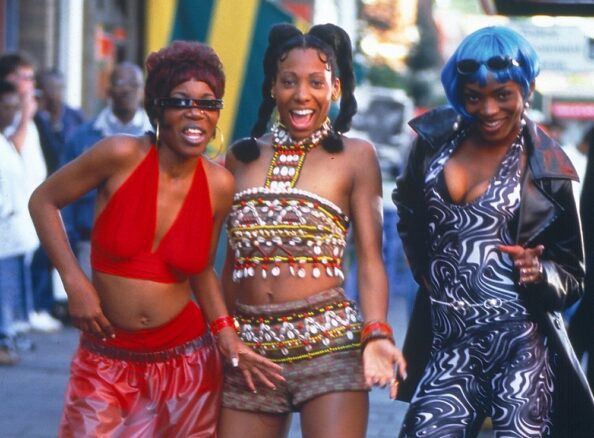

Babymother (1998)

Arriving a year after Don Letts and Rick Elwood’s cult Jamaican reggae film Dancehall Queen, Babymother shines a spotlight on the UK version of the musical craze.

Played by the striking Anjela Lauren Smith, Anita is the eponymous ‘babymother’, raising two young children with the help of her mother Edith (Burning an Illusion star Corinne Skinner-Carter) on a gloomy north-west London estate. Byron, her babies’ father (and a local reggae star), invites her to perform at his show, but reneges on the offer. The frustrated Anita launches her own group, but her world turns upside down when family tragedy strikes.

Made for television, Babymother is a fun, colourful, and strangely haunting look at an all-black London district arguably as mythical as Richard Curtis’s notoriously whitewashed Notting Hill (1999). Its secret star is costume designer Annie Curtis Jones, who conjures an endless stream of impossibly colourful costumes for Anita and her bandmates to wear. Their outlandish beauty is the gateway out of the ordinary and into the realm of the magical for Anita and viewer alike.

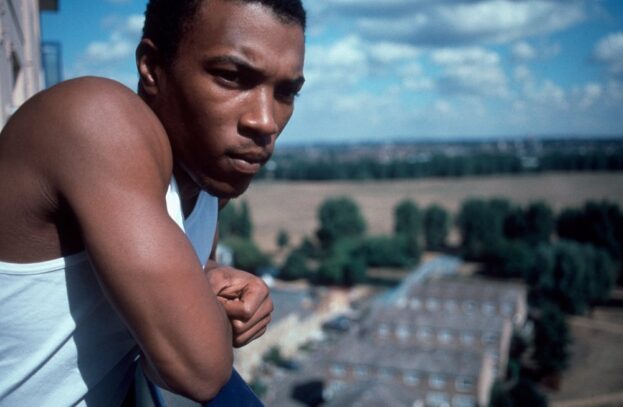

Bullet Boy (2004)

Directed with impressive sensitivity by former documentarian Saul Dibb, Bullet Boy is a bleakly compelling study of two black brothers from Hackney, east London. The elder, Ricky (Ashley Walters), is just out of his teens, and prison; the younger, Curtis (Luke Fraser) is only just discovering his manhood. Ultimately, they both wind up caught up in a spiral of events over which they have little control.

Of the fount of films and television shows to focus the effects of gang and gun crime on London’s black community (Adulthood, Kidulthood, Top Boy, and so on), Bullet Boy remains the least clichéd, and the most engaging, carefully considered and aesthetically successful.

The Stuart Hall Project (2013)

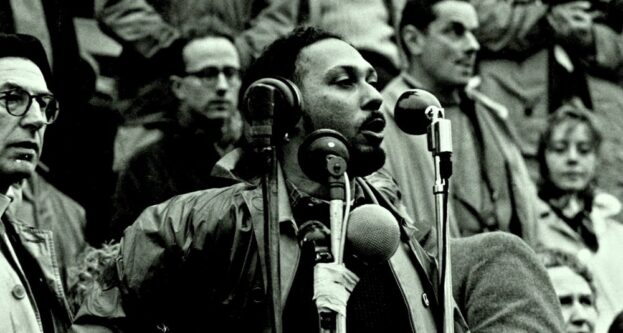

As a founder member of the trailblazing Black Audio Film Collective, John Akomfrah has long been one of the key figures in documenting black British life. The BAFC’s first film, Handsworth Songs (1986), for example, was an extraordinary, collage-like essay based on the idea that the social unrest in the eponymous area was the result of the protracted suppression of black presence by British society.

In the 90s, BAFC morphed into a new outfit, Smoking Dogs, and its most recent film release is this sumptuous portrait of the Jamaican-born, British-based cultural studies pioneer Stuart Hall, who has since sadly died. Culled from over 100 hours of archival footage featuring the great man himself, The Stuart Hall Project unfolds simultaneously as a tribute to this heroic figure and his relationship with Britain, a study of the emergence of the New Left and its attendant political ideas, and a summation of the key characteristics of Akomfrah’s body of work thus far (intertextuality, archival manipulation, a rigorous focus on postcolonial and diasporic discourse). It would also be remiss not to mention the stunning Miles Davis soundtrack.

Belle (2013)

Set on the cusp of the beginning of the abolition process at the end of the 18th century, Belle tells the fictionalised version of the true story of Dido Elizabeth Belle (a star-making turn by Gugu Mbatha-Raw), the mixed-race daughter of British naval officer John Lindsay and an African woman.

Dido’s care is entrusted to Lord Mansfield (Tom Wilkinson), who also happens to be the highest judge in the land. Here, Dido must navigate her transition into womanhood while at the whim of perplexing social codes: she finds herself too high in rank to dine with the servants, but too low in status, on account of her skin colour, to dine with her family. When Dido gets wind of the Zong massacre – a horrifying incident in which approximately 142 enslaved Africans were killed – her stirring ascension to the position of unlikely activist begins.

As well as creating a refreshingly unorthodox heroine for a new generation, Belle is astute on complex social interactions. One of its most subtly affecting threads tracks Dido’s relationship with the Lindsays’ black servant Mabel (Bethan Mary-James), who helps our heroine come to terms with her identity.