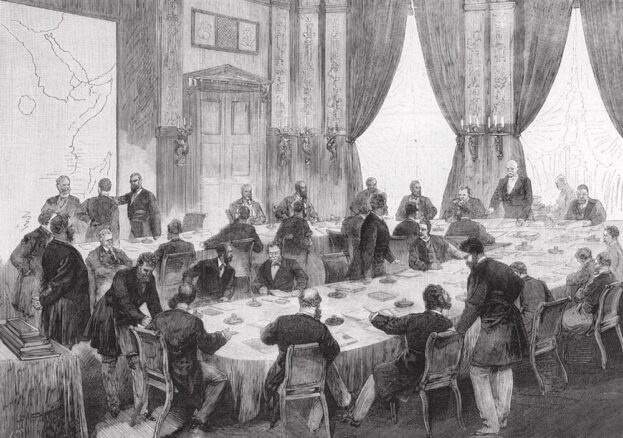

In the winter of 1884, European diplomats gathered in the grand drawing rooms of Berlin to divide the African continent among themselves. Without a single African representative present, these men carved up Africa with little regard for its people, cultures, or histories. Maps of the continent were unfurled on polished tables, and with the stroke of a pen, ancient kingdoms were dismantled, ethnic groups divided, and borders drawn by those who had never set foot on African soil.

The Berlin Conference formalised the “Scramble for Africa,” launching a wave of colonial domination that would exploit the continent’s people and resources for decades. But while the borders drawn in Berlin still define Africa today, they also sparked a powerful response—a movement of unity and resistance known as Pan-Africanism.

The Partition of Africa

By the late 19th century, Europe’s imperial ambitions were at their height. With the industrial revolution in full swing, Africa’s vast resources became essential to the economic expansion of European powers. The Berlin Conference, held between 1884 and 1885, was convened to prevent conflict among European nations as they raced to claim territory across the continent. But for Africans, the outcome of this conference brought decades of exploitation and upheaval.

Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, and other European powers divided Africa without consideration for the people living there. Britain secured territories like Nigeria, Kenya, and Egypt, while Belgium claimed the Congo Free State, a colony that became notorious for its brutal exploitation under King Leopold II. Traditional governance systems were dismantled, ancient cultures were disrupted, and millions of Africans were forced into labour to support Europe’s industrial ambitions. The borders drawn by the Europeans would later fuel conflicts that still affect the continent today.

The Birth of Pan-Africanism

Even as Africa was being divided, a new movement began to take shape—one that would challenge the colonial powers and call for the reunification of African people. Pan-Africanism, a movement focused on the unity, independence, and self-determination of African people, emerged as a direct response to the fragmentation and oppression caused by colonial rule.

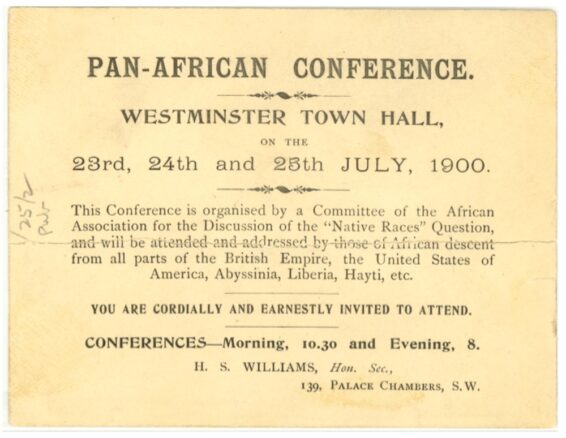

The seeds of Pan-Africanism were sown in the African diaspora. In 1900, Trinidadian lawyer Henry Sylvester Williams organised the first Pan-African Conference in London. This gathering brought together intellectuals, activists, and leaders from Africa and the diaspora to discuss the challenges posed by colonialism and to advocate for the rights of African people globally. While small in scale, this meeting marked the formal beginning of the Pan-African movement.

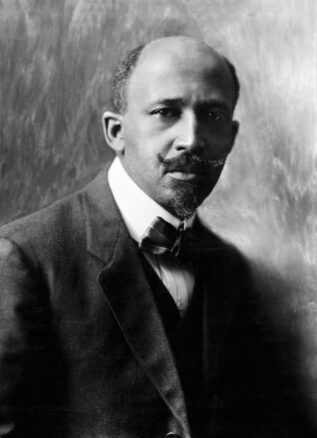

Figures like W.E.B. Du Bois argued that the struggles faced by African people across the globe were interconnected. Du Bois saw Pan-Africanism as a powerful vehicle for uniting Africans and people of African descent in a collective fight for equality, justice, and self-determination. Simultaneously, Marcus Garvey championed Black pride and economic self-reliance, laying the groundwork for a nationalist vision of Pan-Africanism. His founding of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and promotion of the “Back to Africa” movement reflected his belief that African descendants could reclaim their identity and power by building a strong, united Africa.

Pan-Africanism in Action: The Fight for Independence

As the 20th century progressed, the ideals of Pan-Africanism became a rallying point for African leaders fighting for independence. Kwame Nkrumah led Ghana to become the first sub-Saharan African nation to gain independence in 1957. Nkrumah, deeply influenced by Pan-African thought, envisioned a United States of Africa—a political and economic federation that would stand as a powerful force on the global stage. He saw Pan-Africanism as the key to overcoming the divisions imposed by colonial borders and achieving true sovereignty.

Nkrumah wasn’t alone in this vision. Leaders like Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya and Julius Nyerere of Tanzania played pivotal roles in their countries’ liberation and were staunch advocates of Pan-Africanism. Kenyatta, after leading the struggle against British colonialism, became Kenya’s first prime minister and later president, pushing for African unity. Nyerere, known for his principles of “Ujamaa” (African socialism), helped to shape the decolonisation of Africa and remained a vocal supporter of Pan-African unity throughout his life.

These leaders helped create the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, an institution designed to foster cooperation among African states and support decolonisation efforts. Though the dream of a fully united Africa remains unrealised, the OAU—now the African Union—continues to carry forward the legacy of Pan-Africanism, fostering political and economic collaboration across Africa.

Pan-Africanism and the Black British Experience

In Britain, while Pan-Africanism inspired movements abroad, it also shaped the fight for civil rights and racial equality at home. Black British communities, composed of people from Africa, the Caribbean, and beyond, drew upon these ideas as they organised against racism and discrimination.

Figures like John La Rose, who founded New Beacon Books and championed Black literature and education, were crucial in promoting Black cultural identity in Britain. Olive Morris, an activist and co-founder of the Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent (OWAAD), fought for the rights of Black and Asian women and played a key role in campaigns around housing, education, and policing. Stuart Hall, a pioneering cultural theorist, influenced how race and identity were understood in Britain and internationally. Meanwhile, Darcus Howe and Bernie Grant worked tirelessly to address the issues facing Black communities in Britain, advocating for systemic change in policing, education, and political representation.

While not all of these figures were directly tied to Pan-Africanism, their work contributed to the broader goals of Black empowerment and solidarity. Their efforts helped lay the foundations for today’s Black British identity, a rich tapestry of cultures and histories united by a shared commitment to equality and justice.

The Cultural Influence of Pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism’s reach extended beyond politics into the arts and culture. Figures like Fela Kuti, the Nigerian musician and activist, used his music to address social and political issues in Africa, often drawing on Pan-African themes. Kuti’s Afrobeat music became a powerful form of resistance, promoting African pride and challenging corruption and colonial legacies.

In the Caribbean and the United States, Pan-Africanism influenced the work of writers, poets, and musicians who sought to reclaim African heritage and express solidarity with the struggles for independence and civil rights. This cultural influence helped galvanise movements for racial justice worldwide, reinforcing Pan-Africanism’s role as a global force for change.

The Legacy of Pan-Africanism Today

The Berlin Conference may have divided Africa, but Pan-Africanism arose as a force that sought to reunite its people. The movement’s ideals of unity, self-determination, and liberation continue to inspire activists and leaders across Africa and the diaspora. In a world where the legacies of colonialism still cast long shadows over global politics, Pan-Africanism remains a vital philosophy for those working to build a more just and equitable future.

Today, the African Union continues the work begun by Pan-Africanists over a century ago, promoting peace, development, and integration across the continent. Meanwhile, in the diaspora, the principles of Pan-Africanism remain central to movements for racial justice and Black empowerment. From the streets of Accra to the communities of London and New York, Pan-Africanism endures as a symbol of resilience, resistance, and hope.