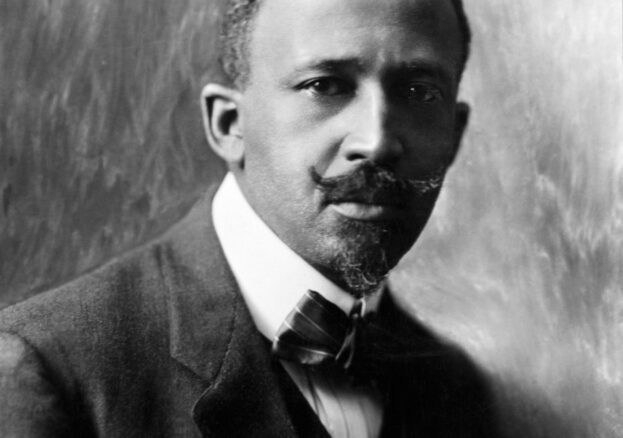

W. E. B. Du Bois was born on 23 February 1868, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, a small New England town where he was raised in a predominantly white community. His early life was marked by a distinct contrast: while he grew up in a relatively integrated community, he still experienced the sting of racism and exclusion, experiences that shaped his intellectual and activist future. At the time of his birth, the United States was a nation in transition—just three years after the end of the Civil War, and in the midst of Reconstruction, the political, social, and economic landscape for African Americans was still in flux.

Du Bois’ intellectual journey began at Fisk University, a historically Black institution in Tennessee, and later continued at Harvard University, where he became the first African American to earn a doctorate in 1895. While at Harvard, Du Bois was exposed to the academic rigour that would later define his career. He was deeply influenced by the progressive intellectual climate at the university, where he honed his critical thinking skills and began to question the prevailing attitudes toward race in America. Despite the racial barriers he encountered, Du Bois’ commitment to academic excellence and the study of race and history would set him apart from his contemporaries.

His time at Harvard, however, also left him with a sense of frustration. While he had been afforded educational opportunities, he understood that the majority of Black Americans were denied the same privileges. This stark contrast between his own opportunities and the limited access for others fuelled his growing desire to use his knowledge and skills to advocate for the rights of African Americans.

Upon completing his doctorate, Du Bois became a prominent intellectual figure in the African American community. In 1897, he was appointed to the faculty of Atlanta University in Georgia, where he taught for over two decades. This period was formative for Du Bois, as he conducted ground-breaking research into the social conditions of Black Americans. His work at Atlanta University was more than just academic; it was deeply intertwined with his activism. He conducted studies on topics such as education, economic inequality, and the social status of African Americans, producing data that would later inform his arguments on racial uplift and the need for equal treatment.

The Souls of Black Folk and Double Consciousness

In 1903, Du Bois published his most influential work, The Souls of Black Folk, which remains a cornerstone of African American literature and critical race theory. Within this work, Du Bois introduced the concept of “double consciousness,” describing the inner conflict African Americans experience living in a society that marginalises their identity. He argued that Black people in America were forced to navigate two identities: one as Americans and one as Black people, often leading to internal conflict and a sense of alienation. This theory resonated deeply with the Black community, as it captured the struggle of trying to live fully in a society that denied Black people basic rights and dignity.

The Souls of Black Folk also set the stage for Du Bois’ further involvement in the fight for racial equality. He used the book as a platform to critique the prevailing racial ideologies of his time, such as Booker T. Washington’s belief in vocational training for Black Americans and his notion of accommodation to the existing social order. Du Bois, by contrast, argued that political and civil rights were paramount, and he advocated for higher education, professional training, and full participation in American democracy.

The Niagara Movement and NAACP

Du Bois was a key figure in the founding of the Niagara Movement in 1905, which was a direct challenge to Washington’s philosophy of gradualism and compromise. The movement, named for the location of its first meeting near Niagara Falls, called for immediate civil rights, including suffrage, equality before the law, and an end to racial discrimination. This radical stance positioned Du Bois as a leader of a new generation of Black intellectuals and activists who were unwilling to wait for incremental change.

The Niagara Movement eventually led to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) in 1909. Du Bois became the editor of The Crisis, the NAACP’s influential magazine, where he championed civil rights, and his editorials and writings helped shape the direction of the civil rights movement. He was a vocal critic of lynching, segregation, and discrimination, and his work with the NAACP established him as a formidable force in the fight for equality.

The Talented Tenth and Intellectual Leadership

One of Du Bois’ most enduring ideas was the concept of the “Talented Tenth,” which he introduced as part of his belief that the top 10 percent of the Black population should receive the highest level of education and leadership training. Du Bois saw this educated elite as the key to uplifting the rest of the Black community. His belief in the power of higher education and intellectual leadership led him to advocate for institutions that would train and empower future Black leaders, particularly those who could advocate for social, economic, and political change.

Du Bois’ views on education and leadership were central to his identity. He was not only a scholar but also an activist who believed that intellectual development should be paired with action. His work was not about academic theory alone; it was about applying knowledge to real-world struggles. He emphasised the role of education in achieving political power and used his platform to challenge the racial status quo.

Shift Toward Pan-Africanism and Socialism

Du Bois’ worldview expanded over time, particularly after World War I and the rise of colonial independence movements in Africa. He became increasingly involved in Pan-Africanism, a movement that sought to unite people of African descent around the world and fight for their political and economic liberation. He attended multiple Pan-African Congresses, where he advocated for the rights of African colonies and the empowerment of Black people across the globe.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Du Bois’ political views shifted toward socialism, largely due to his growing disillusionment with capitalism and the economic inequalities that persisted in the U.S. He became a vocal critic of American imperialism, racism, and capitalist exploitation, and his views continued to evolve as he engaged with global political movements.

In 1961, at the age of 93, Du Bois moved to Ghana, where he was granted citizenship by its first president, Kwame Nkrumah. Du Bois had long been supportive of African liberation movements, and his relocation to Ghana marked his commitment to these causes. He spent his final years there, writing and reflecting on the global struggle for freedom and justice. Du Bois passed away on 27 August 1963, just days before the March on Washington, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would deliver his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

Legacy and Influence

W. E. B. Du Bois left behind a legacy that spans the realms of scholarship, activism, and global liberation. His work on race, identity, and civil rights challenged the foundations of racism and colonialism, and his contributions to Black intellectual thought laid the groundwork for future generations of activists and scholars. He was an outspoken critic of the systemic racism that permeated American society, and his commitment to fighting for justice, equality, and human dignity continues to resonate today.

Du Bois’ life was marked by a ceaseless pursuit of knowledge and a tireless dedication to the cause of justice. He understood that true freedom and equality could not be achieved without confronting the deep-seated inequalities in society—and he spent his life doing just that. His work remains relevant in discussions on race, identity, and social justice, and his intellectual contributions continue to influence fields as diverse as sociology, history, and political science.

Through his writings, activism, and leadership, Du Bois proved that intellectual rigour and social change were inextricably linked. He showed that knowledge, when applied with purpose and passion, could be a force for profound transformation. W. E. B. Du Bois may have left this world in 1963, but his ideas and actions continue to inspire the fight for justice and equality.