These are the words of Maria W Stewart (1803-1880), the first African-American woman to give public lectures. Remarkably prescient too, against the background in which they were uttered – in the heart of American slavery and virulent racism, where the status of the Black woman was the lowest in American society.

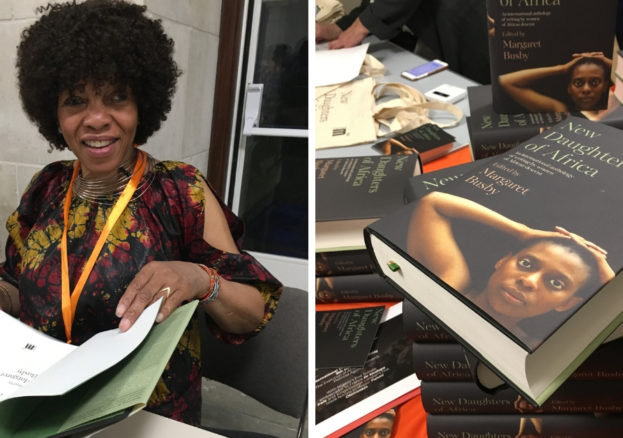

Stewart’s declaration serves as the impulse for New Daughters of Africa: An International Anthology of Writing by Women of African Descent edited by Margaret Busby, published in early 2019 by Myriad. This new book is a follow-up from Margaret Busby’s 1992 highly-acclaimed and path-breaking anthology, Daughters of Africa.

For the general reader of any gender, the historical sweep and diversity of this literary compendium is staggering, with judiciously selected works of African and African- Diasporan women. New Daughters of Africa is divided up as follows: Pre-1900, 1900s, 1920s,1930s, 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.

Over the course of its 805 pages, the tome showcases the work of more than 200 women writers in the form of memoir, short stories, speeches, novel extracts, poetry and journalism. Well known and obscure contributors include Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Patience Agbabi, Malorie Blackman, Edwidge Danticat, Esi Edugyan, Bernardine Evaristo, Roxane Gay, Karen Lord, Warsan Shire, Zadie Smith. The book begins with a Lamentation penned by Nana Asma’u (the daughter of Shehu Usman dan Fodiyo, founder of the 19th century Sokoto Caliphate) for her friend Aysha, and ends with Sunita, by Chibundu Onuzo.

In her introduction to the New Daughters of Africa, Busby says: “Custom, tradition, friendships, mentor/mentee relationships, romance, sisterhood, inspiration, encouragement, sexuality, intersectional feminism, the politics of gender, race and identity—within these pages is explored an extensive spectrum of possibilities, in ways that are touching, surprising, angry, considered, joyful, heartrending. Supposedly taboo subjects are addressed head-on and with subtlety, familiar dilemmas elicit new takes.”

Every Black home should own a copy of the book.

The literary voices of Black women need to be heard even more urgently now.