Not many will have heard the name Asquith Xavier, nor will they be aware of how the brave family man who faced racial discrimination in the workplace managed to beat the “colour bar”.

Just a little over five short decades ago, Asquith Xavier, applied for a promotion that would see him move from Marylebone to Euston Station in 1966. But astonishingly, at the time there was an informal ban on Black workers holding railway jobs where they met the public, and he was turned down.

Asquith Camile Xavier was born on July 18, 1920, on the island of Dominica in the West Indies, then a British colony. Like many of the Windrush generation, he answered the British government’s call for those in the Caribbean to move to Britain to help rebuild the weakened economy following WWII. There were severe labour shortages, so Commonwealth citizens were invited to travel over to Britain. Asquith boarded the TN. Ascania in his capital city of Roseau and docked in Southampton on April 16, 1958.

Settling in Paddington, West London, he gained employment with British Rail as a porter before progressing to guard at Marylebone depot. In 1966, when the freight link at Marylebone depot was closed, he applied for a transfer to London Euston station.

Asquith was told that he was denied the job due to an unofficial “colour bar” which operated at the station, excluding Black people from working in customer-facing roles. Dissatisfied with this decision, Asquith campaigned to end the racial discrimination practiced by British Rail.

The first Race Relations Act was passed in 1965 making it illegal to discriminate on the grounds of colour, race, ethnic or national origins in public places. But the railways were not considered public and somehow Asquith’s story gained traction. With the support of Jimmy Pendergast (NUR Branch Secretary) and Barbra Castle (Secretary of State for Transport), Asquith’s hard-fought battle meant that, on August 15, 1966, he became the first non-white guard to be employed at Euston Station. Asquith refused to accept discrimination and his quiet determination not only ended in him securing the job, but his pay was backdated to when he had first applied for the position. Subsequently, the Commission for Racial Equality was created. His campaign also led to the strengthening of the Race Relations Act (1968) which made it illegal to refuse housing, employment or public services to people because of their ethnic background.

On the day Asquith started at Euston, station manager Ernest Drinnan said: “We expect Mr Xavier to fit in very well here… His record at Marylebone was exceptionally good and we know everyone here will take to him.”

Sadly, this wasn’t quite the case and his victory came at a cost. He received race hate from the public and threats to his life, so required Police protection on his way to and from work.

Presenting the Bill to Parliament, then Home Secretary Jim Callaghan said: “The House has rarely faced an issue of greater social significance for our country and our children.”

In 1972, Asquith and his family moved from London to Chatham, Kent, where he commuted daily by train to work at Euston, but not long after his health began to fail and in 1980, he passed away.

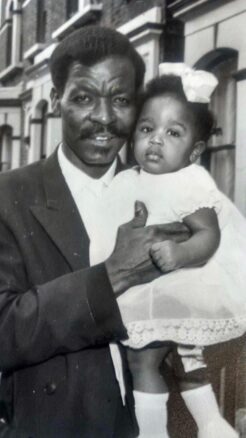

Speaking about my grandfather, Asquith Xavier, and his advancements in gaining equal opportunities for the non-white community in the workplace, fills me with an overwhelming sense of pride. His dignity, strength of character and tenacity in the face of adversity makes me feel honoured to carry the Xavier name. His contribution to our society has undoubtedly shaped the way we live today and should be celebrated and never forgotten. His legacy has made a lasting impression on me and taught me that with matters of discrimination, the pen can be mightier than the sword.

My grandfather’s approach to racial injustice managed to bring about a change in employment legislation of the time. This was not only a significant step in the right direction towards equal opportunities for the Windrush generation, who faced overt racism and prejudice daily, but also paved the way for future generations. For this I am truly grateful.

My grandfather’s approach to racial injustice managed to bring about a change in employment legislation of the time. This was not only a significant step in the right direction towards equal opportunities for the Windrush generation, who faced overt racism and prejudice daily, but also paved the way for future generations. For this I am truly grateful.

Unfortunately, recent actions have shown that in Britain, racism did not end back in the 60’s with the passing of these laws. Sadly, it is all too often the case that your ethnicity can determine your destiny. This is evident with the backlash received by the three words “Black Lives Matter”.

Like many, I have been both inspired and concerned by the recent global Black Lives Matter movement, which has drawn attention to Britain’s past and present record on racial injustice. This coinciding with my grandfather’s centenary has helped shed light on his achievements within British race relations. But it is bittersweet for our family. Not only because he sadly passed away aged just 59, but also because this milestone comes at a time where, despite his efforts and despite the race relations act, it is evident that we are not yet living in an anti-racist society. Black and mixed-race people are still under-represented, and their achievements largely omitted from the national curriculum, where it would be well-placed to improve unconscious bias and racial discrimination in the next generation.

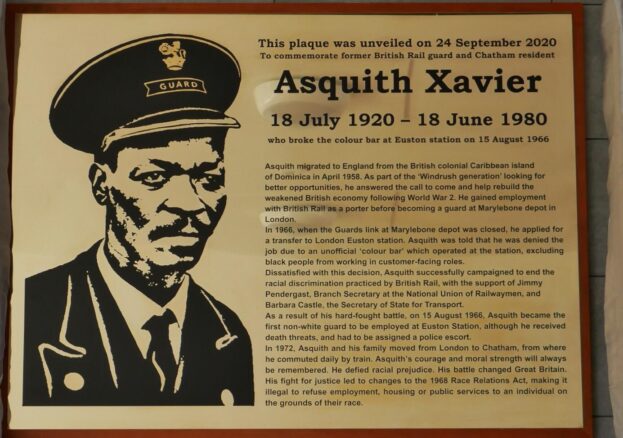

During Black History Month 2016, Network Rail revealed a plaque in honour of my grandfather at Euston Station. Four years on, in the year we would have celebrated his 100th birthday, a brass mural detailing how Asquith Xavier overcame racial injustice in the campaign for equality in Britain, has been unveiled in Chatham, Kent. This local appreciation acknowledges his legacy as part of modern-day history, which will hopefully lead to nationally recognition of our unsung hero. Chatham was the place he travelled from and to daily, in the town he called home and where he was laid to rest, so it was significant to have a have record of his legacy locally.

The production of this plaque was supported by Chatham’s Labour Councillors Sijuwade Adeoye and Vince Maple. I was truly humbled that Network Rail, Southeastern Railway and RMT came together to pay a special commendation to Asquith Xavier, in honour of his contribution to our multi-cultural society. It is a place where we can bring our children to be educated about his pioneering ways and for the general public to learn of an ordinary man who achieved extraordinary things by standing up against systemic racism. I hope that his bravery will help to inspire others to also stand up for what they believe in and what is right.

I am deeply upset as I never got to meet my granddad, but I am also hugely proud and feel a sense of duty to take the baton and advance the work he started to eliminate racial inequality, disadvantage and discrimination. I have addressed my local MP, the Minister of State at the Department for Education, and written to Boris Johnson to ask him to make learning about Black historical figures compulsory in schools. I don’t think there should be just one month dedicated to it, it needs to be integrated as part of the national curriculum. The national curriculum needs to be brought up to speed to include the positive achievements of Black, mixed-race and people of other ethnicities which are very relevant in both local and British history.

I am deeply upset as I never got to meet my granddad, but I am also hugely proud and feel a sense of duty to take the baton and advance the work he started to eliminate racial inequality, disadvantage and discrimination. I have addressed my local MP, the Minister of State at the Department for Education, and written to Boris Johnson to ask him to make learning about Black historical figures compulsory in schools. I don’t think there should be just one month dedicated to it, it needs to be integrated as part of the national curriculum. The national curriculum needs to be brought up to speed to include the positive achievements of Black, mixed-race and people of other ethnicities which are very relevant in both local and British history.

I hope that by the time my children reach school-age, their mainstream education will include learning about Black people who made a positive impact on British culture such as Ignatius Sancho, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Mary Seacole and Asquith Xavier. These people helped shape this country and teaching of their accomplishments may help address issues of prejudice and bias, assisting cohesion within the multi-cultural Britain we live in today.

What my grandfather was able to justify over 50 years ago, was not just that Black Lives Matter but that the quality of life of black people matters equally.

Camealia Xavier-Chihota is a grand-daughter of Asquith Xavier