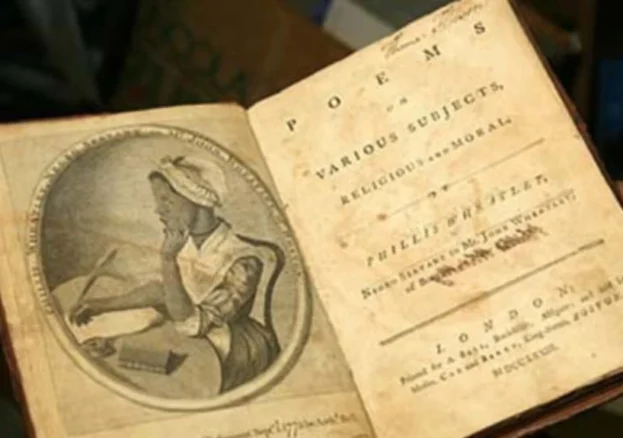

In the summer of 1773, Phillis Wheatley arrived in London. A poet since the age of 12, Phillis was in London for the publication of her work; making her the first African American woman to see her book in print. The publisher was Archibald Bell, a bookseller based at 8, Aldgate. Today the address is occupied by a hotel and much of the Georgian city which Phillis saw has changed over the last 200 years of urban development. This raises the question of how we can build an understanding of historical figures within their contemporary environment. For Phillis Wheatley, her lived environment covered West Africa (probably present-day Gambia or Senegal), North America (Boston, part of the British Colony of Massachusetts until 1783) and Britain (London). Her visit to London offers an opportunity to explore her encounter with Georgian London and locate her confidentially within a time bonded landscape.

Phillis travelled to London with Nathaniel Wheatley; the adult son of the family who had purchased Phillis when she arrived in Boston harbour on 11 July 1761. Her African birth name is unknown. The name she was given aged 7 or 8 years old was a combination of the ship on which she was forcibly transported across the Atlantic,The Phillis, and the surname of the family for whom she worked as an enslaved domestic servant. Phillis learnt to read and write and was soon reading Greek and Latin texts including Homer, Horace and Virgil. The work of Alexander Pope and John Milton inspired her to write poetry and her first published poem appeared on 21 December 1767 in the Rhode Island. A 1772 proposal to publish a collection of her poems in Boston proved unsuccessful, however a connection with Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, introduced Phillis to a publisher in London.

There is evidence from Phillis herself about her six week stay in the capital in a letter written to an Connecticut acquaintance, Colonel David Wooster. In the letter (dated 18 October 1773) Phillis writes,

Grenville Sharp Esqr. Who attended me to the Tower & Show’d the Lions, Panthers, Tigers, &c. the Horse Armoury, small Armoury, the Crowns, Sceptres, Diadems, the Font for christening the Royal Family. Saw Westminster Abbey, British Museum, Coxe’s Museum, Saddler’s wells, Greenwich Hospital, Park and Chapel, The royal Observatory at Greenwich, &c. &c. too many things & Places to trouble you with in a Letter.

Abolitionist Grenville Sharp, with whom Phillis toured the Tower of London, was involved in the Somersett case (1772) whereby The Lord Chief Justice ruled that James Somersett, an enslaved African brought to England from Boston by his owner, could not be legally forced to return to the colonies. Phillis must have been aware of her own legal status in London and how this would change on her return to Boston. Fortunately, in late 1773 (shortly before her emancipation in early 1774) she was able to write to a friend that,

Since my return to America my Master, has at the desire of my friends in England given me my freedom. The Instrument is drawn, so as to secure me and my property from the hands of the Executrs. adminstrators, &c. of my master, & secure whatsoever should be given me as my Own.

Besides Grenville Sharpe, Phillis met other scholars and dignitaries including Swedish naturalist Daniel Solander, American polymath Benjamin Franklin, Lord Mayor of London Frederick Bull and writer Mary Palmer. An audience with King George III was arranged, but Phillis had returned to Boston before it could take place.

Phillis’s letter also gives us an insight into her itinerary and highlights the places which probably made the most impression. The first of these is the Tower of London where the grounds included medieval structures such as the White Tower, the Royal Mint, the Crown Jewels and accommodation for a small garrison. Phillis writes about the wild animals she saw, revealing a former function of the Tower as home to a menagerie of wild animals given as royal gifts. A view of the Tower from 1737 shows us that when Phillis toured the complex, the southern edge ran down to the waters of the Thames; a busy throughfare for commercial boats. Modernisation of the river bank (Victoria Embankment) did not begin until 1865, and in 1773 the infamous Traitor’s Gate still opened directly onto the waterfront.

British Museum

Some places Phillis visited, such as Westminster Abbey and Greenwich Park, remain popular tourist destinations today. Others no longer exist due to subsequent rebuilds or the short term nature of the establishment. Her use of the word ‘saw’ in relation to some sites raises an intriguing question around whether she ‘saw’ the exterior as she travelled past or went inside. Within this category, Phillis mentions Sadler’s Wells where a brick building had been put up in 1765 to replace the original wooden structure. In March 1765, Lloyds’ Evening Post reported that ‘Sadler’s Wells is now rebuilt and considerably enlarged; each of the entrances is decorated with an elegant iron gate and pallisades [with] a degree of splendor and magnificence …’ It was this celebrated new build that Phillis experienced.

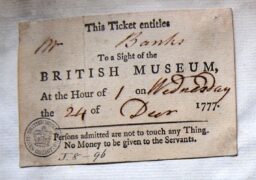

Other attractions listed in the letter were famous for their exhibits. For example, at this point in its history the British Museum housed not only historical artefacts but a huge library, medieval manuscripts and a natural history collection. By 1773, the Museum was open to ‘all studious and curious persons’ who could apply for a free ticket to join a timed tour. The British Museum Archives (plus early documents now held by the British Library) do not include any visitor listings for Phillis Wheatley or Nathaniel Wheatley. However, not all visitor records survive and we may never know conclusively if Phillis viewed the collection.

British Museum J,8.96

However, two views of Montagu House dated 1770 and 1778 respectively show us what Phillis would have seen as she travelled along Great Russell Street in 1773. At the time, the British Museum was housed in a former aristocratic residence with a gatehouse giving access to the courtyard and main buildings (all demolished during the 1800s rebuilt). The views show the brick Montagu House with glimpses in one of recent stone clad Georgian construction projects beyond. The views also suggest the different methods by which Phillis might have travelled around the city by foot, sedan chair or horse drawn carriage. Street furniture includes the system of public oil lamps introduced 20 years previously to illuminate streets at night.

The other museum mentioned by Phillis is Cox’s Museum in Spring Gardens, Charing Cross. This was opened the year before Phillis arrived in London by goldsmith James Cox as a showcase for his work. An advertisement in the London Evening Post (22 February 1772) indicates that Cox aimed to attract ‘Nobility and Gentry’ to view the display of clocks and jewellery and admission was a costly ten shillings and six pence. The museum closed in 1775 after the exhibits went up for sale. Again, we do not know if Phillis passed by or went inside, and any answer must be purely speculative. For a wealthy Boston family, the entrance price would not have been prohibitive and we know that Phillis was expecting money from the sale of her book. In addition, admission included a catalogue of the exhibits and while Phillis may not have felt moved to mention the clocks on display, we know that she had a love of printed material. While in London she bought the works of Alexander Pope, the satirical poem Hudibrass by Samuel Palmer, the novel Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes, John Gay’s Fables (poems based on Classical myths) and was given a copy of John Milton’s Paradise Lost. The inclusion of a printed catalogue could well have been a motivation to view the exhibits for an avid reader and bibliophile.

By September 1773, Phillis was back in Boston where she received copies of her book. She left the Wheatley household and on 26 November 1778, married John Peters, a free African grocer and barber with a shop on Court Street in the city. Then in late 1779, Phillis ran advertisements requesting subscribers for a book containing 33 poems and 13 letters. The proposal was unsuccessful although some poems appeared individually in pamphlets and newspapers, including one written under the name Phillis Peters. Phillis, who suffered from chronic asthma, died on 5 December 1784 aged 31. Two posthumous collections of her work were published in Boston (1834 and 1838) helping to create a lasting legacy to a learnt woman who strove to ensure her voice was heard through her personal correspondence and her published works.