Going Beyond Street Activism: A Historical Background From Race Riots, Reparations Marches To Black Lives Matter Taking Over The Streets

Kwaku

Today, August 1 2017, hundreds, if not thousands, of Africans from not just London, will march from Windrush Square in Brixton, south London to Westminster, where they’ll hold a rally on Parliament Square, whilst a delegation hands over a petition at the nearby Downing Street residence of Prime Minister Theresa May.

Ordinarily, this fourth incarnation of the annual Afrikan Emancipation Day Reparations March ought to be the biggest thus far. But being a weekday and what looks likely to be a wet day, we’ll see what transpires later in the day.

Incidentally, the much longer established Notting Hill Carnival, where tens, if not hundreds of thousands of Africans take to the streets of the Notting Hill area of London in late August, has been in the news of late. The Grenfell Tower tragedy has been used by some as an excuse to push the Carnival off the streets it has traversed for some fifty into a neighbouring park, where it can be better “controlled”.

But first things first. 2017 marks the third year of the UN’s International Decade For People Of African Descent (IDPAD) initiative. For some, this is an opportunity to challenge racism in different ways, particularly as we face the rise of racism and xenophobia in a post-Brexit Britain. And today’s march is as good a reason to highlight some of the history of activism on the streets of Britain.

IDPAD recognises that people of African* heritage, wherever they are on the planet, face discrimination and racism. The aim of the Decade, which runs from 2015 to 2024, is for member states and civil society organisations to put systems in place to address the discrimination, racism, and other injustices and inequalities experienced by Africans, particularly in areas such as employment, housing, health, education, and the justice system.

Often, the only way to resolve or highlight systemic racial discrimination and disadvantage is to take to the streets, be it protest marches, rallies, or riots. The violence or destruction that comes with riots is unfortunate, but even Martin Luther King Jr, the famous non-violence advocate empathised, and described riots, which are often responses to unaddressed social ills, as “the language of the unheard.”

In Britain, the history of the African British experience is heavily punctuated with racism. Not surprisingly, there is also a history of contestations on the streets which go back a long way. But is it time to change tack in dealing with the disadvantages, grievances and injustices faced by Africans, particularly as we are in the third year of IDPAD?

In the spirit of Sankofa, in order to move forward, we need to take cognisance of what has gone on in the past.

1919 is perhaps a good starting point, in that for much of that year, particularly between April and August, there were race riots not just in London, but also in other seaports in England, Scotland and Wales, such as Liverpool, South Shields, Salford, Hull, Glasgow, Newport, and Barry.

The riots were mainly a consequence of the acute unemployment and housing shortage immediately after World War I, and the abhorrence some European men had of seeing their women fraternising with Africans and non-Europeans, many of whom were seamen who were perceived as taking jobs away from the British.

On August 23 1958 race riots kicked off in Nottingham, and escalated for nearly a week in the Notting Hill area of London before the month was over. The Africans, mostly recent immigrants from the Caribbean, stood their ground and responded in kind to the violent attacks by racist young Europeans.

To improve community relations after these riots, Claudia Jones, the Trinidadian-born political activist and editor of The West Indian Gazette newspaper, organised an annual indoor, cabaret-style Caribbean Carnival from January 1959 until her death in 1964.

Whilst the Jones-organised carnivals had a political bent, underscored by its ‘A people’s art is the genesis of their freedom’ slogan, today’s Notting Hill Carnival, which started after Jones’ death has in its 50 years simply become Europe’s biggest annual street event and space for African cultural expression.

Devoid of any politicism, it’s a weekend of revelry, a major opportunity for African caterers to sell food and drinks on the procession route, and an opportunity for boisterous merrymakers to blow off some steam at police officers, or show off – at last year’s carnival, an African motorcycle gang was much in evidence exhibiting its revving skills. Sadly, the mainstream media’s coverage tends to be on the African youths’ clashes with the police and the number of arrests.

Politicism and protestations on the streets of London come in the shape of the ad hoc, annual, and what can be described as “guerilla” fashion.

Ad hoc protestations tend to be responses to police brutality, deaths in custody of the state, or verdicts that don’t hold anybody accountable for deaths within state custody. It can also be as the result of the inaction or perceived ineffective police investigations.

The biggest protestation of this kind was the New Cross Massacre Action Committee (NCMAC) organised Black People’s Day Of Action, which took place on March 2 1981. The march started from New Cross in south-east London, where on January 18, thirteen young Africans died in a house fire which many believed was the result of a racially-motivated arson attack.

Many in the African community were disappointed with the police for treating the fire as an electrical accident instead of pursuing the perceived perpetrators, and with the Establishment and media for their failure to publicly express sympathy over the tragic deaths.

Some 15-25,000 Africans marched through Fleet Street, then the base of the national newspapers, where they were met with insults from the windows of the newspaper offices.

The march passed by the Houses of Parliament, where the organisers managed to get an Early Day Motion on the day, which enabled some MPs for the first time to publicly express sympathy and condemn the racist attacks on Africans. Additionally, copies of the ‘Declaration of New Cross’ were handed over to Parliament, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s 10 Downing Street residence, and the Metropolitan Police, before the march ended at Hyde Park for a rally.

In the last three years, the 1st August Afrikan Emancipation Day Reparations March has been developing as an annual political march with the potential of galvanising thousands more Africans unto the streets.

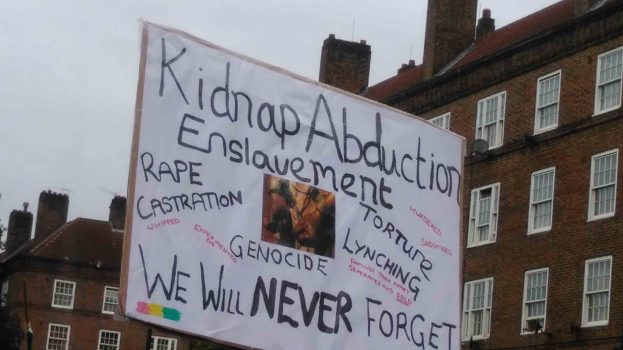

The march starts from Windrush Square in Brixton – the African-Caribbean people’s spiritual home in south London – to Parliament Square for a rally and delivery of the Stop The Maangamizi petition to the Prime Minister’s residence, before heading back to Brixton for more speeches urging the British government to start a reparations programme to deal with its participation in the enslavement and colonisation of African peoples.

This march into the heart of central London attracts scant mainstream media coverage. To militate against this, the organisers of last year’s march held a press conference in a central London hotel, which none of the invited mainstream media attended. They also advertised the march in Metro, a London regional newspaper, which only permitted the advert to run when words such as Holocaust, which the paper deems relevant only in connection to the Jewish experience, had been removed.

Presently the only street-based activism that regularly garners mainstream coverage are the guerilla-styled stunts by Britain’s Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. Disrupting city centre traffic through marches, protestors chaining themselves across streets to disrupt passengers travelling into airports, or even getting European supporters to get on an airport tarmac to disrupt flights, are some of the stunts that have raised their profile within traditional and social media.

On one hand I applaud the adoption of the BLM movement in Britain, as a pan-African show of solidarity with our African-American kith and kin. I admire the energy of the social media-savvy young Africans leading this movement, which also has support from young, liberal, college-type Europeans.

Last July, as a response to the deaths of two African-Americans in the US, there was a BLM march that started out in Windrush Square to the nearby Brixton police station, the scene of several African death in custody cases, where the protestors remonstrated against deaths in the US and UK at the hands of the police. On the return march, just as they were about to end up in the square, someone casually suggested they take over the street.

A few of the protestors hesitantly positioned themselves in the middle of a busy intersection. Soon, what seemed like a temporary detour, turned into a sit-in. Emboldened by the fact that the police made no attempt to move them on, many more joined the chanting from the middle of the street.

When one of the protestors shouted “Today Brixton is locked off,” it was not an exaggeration. For the six hours I was there, until nearly midnight when I left, apart from one ambulance that was let through, no other vehicles, including buses, could get through.

I saw young Africans and non-African activists feeling powerful “running the streets,” but it did not seem there was any concrete plan, besides the chanting “Hands up, don’t shoot,” and “Racist police, off our streets,” and the blocking of a major London thoroughfare. I saw veteran political activist Marc Wadsworth, former head of the Anti-Racist Alliance (ARA), help defuse tension between the protestors and police.

Whilst this particular protest turned out to be peaceful, I worry that there does not seem to be a clear politically-focused strategy following on from the BLM protests against deaths by police. My concern is that it takes only one little incident for the media to turn against them, which could result in this dynamic, youth-led movement imploding.

There is no doubt that taking to the streets has the potential to publicise causes. But to achieve the real goals, activists in 2017 perhaps need to also engage with decision makers. Considering some of the gains made by other minority groups, such as the Jewish people and Asians, without having to regularly take to the streets, African activists should also engage more with the people with powers for making change who reside within the corridors of the political establishments. That is where activists should look to lock-down.

For example in March, fifty-one years after the UN resolved to mark March 21 (in remembrance of the Sharpeville Massacre) as the International Day For The Elimination Of Racial Discrimination (colloquially known Anti-Racism Day), the African MP Dawn Butler moved a debate on the UN initiative in the House of Commons, where she had earlier hosted a reception to introduce the initiative to fellow parliamentarians, community and political activists.

Now that this initiative is within the purview of our politicians, it’s another opportunity for activists to push the politicians to turn the fine words of concern from the Prime Minister and others into programmes that meaningfully mitigate racism.

In her maiden speech as Prime Minister in July last year, Theresa May highlighted some of the discrimination faced by Africans, saying “If you are black, you are treated more harshly by the criminal justice system than if you are white.” But this does not necessarily mean the Conservative government under her leadership is about to seriously make changes to deal with the issues or take up its IDPAD obligations.

Although her government’s response to enquiries about IDPAD elicits a “no specific plans” answer, activists nevertheless need to challenge her on not only her mission “to make Britain a country that works for everyone” but also United Kingdom’s obligations to effectively address the structural issues that give rise to UN initiatives such as IDPAD, Anti-Racism Day, and the International Convention On The Elimination Of All Forms Of Racial Discrimination.

It’s worth noting that it’s only in recent times that the Conservatives have been able to attract Africans away from their traditional political home, which is the Labour Party. So although since 2005 the Conservatives have been slowly producing African MPs, and currently have five including Prisons Minister Sam Gyimah, compared to Labour’s eight, many Africans do not see the Conservatives as the party to redress the issues that traditionally play out on the streets.

Among the thousands returning to, or supporting, the Labour Party since the socialist Jeremy Corbyn became party leader, are a growing number of Africans and African-led Corbyn-supporting Momentum and related groups that have launched since last year. Additionally, during the recent general election, a number of community activists and artists who in the past did not vote or do “politics with a capital p”, were moved to publicly declare their support for the Labour leader and their intention to vote Labour.

In a bid to gather support for Labour, party activists have positioned their party as the only alternative for Africans. They point to the fact that all the Race Relations laws came from Labour governments. Africans also have key shadow cabinet posts, such as 30 year parliamentary veteran Diane Abbott, and newbie Kate Osamor, who entered parliament after the 2015 general election.

The fact that Corbyn is a long-standing anti-racism campaigner is another reason put forward for aligning with Labour, in the hope that a Corbyn-led government will be better placed to deal with the discrimination, injustices and racism suffered by Africans.

The internet is not just useful for publicing activities – those who don’t necessarily want to be on the streets can put out online petitions. There’s even a government-run petitions website through which getting 10,000 signatures means the government will provide a written response, whilst 100,000 signatures means the issue will be considered for debate in parliament.

In 2017 activists should be engaging more with the power of lobbying for political change or intervention. In the absence of paying for professional lobbyists, being within or around party politics is one of the effective ways open to most ordinary people to lobby in order to influence political decisions.

For example, the reparations movement’s Stop The Maangamizi petition includes a call for an All-Party Commission Of Inquiry For Truth & Reparatory Justice. But this cannot be achieved without engaging with the parliamentary process through lobbying across party lines.

Whilst I admire the energy of the young activists, it’s worth pointing out that in traditional African communities great value is put on the wisdom and experience of the elders. African proverbs like “The wisdom of the elderly is like the sun, it illuminates the village and the great river” or “A village without the elderly is like a well without water” should encourage younger activists to tap into the knowledge and experience of those who’ve been before.

Whilst the Reparations march and the BLM movement show that there are many young activists on the ground, there’s a general admission that there is no formal process whereby the baton and experience is handed by the elders to the young activists.

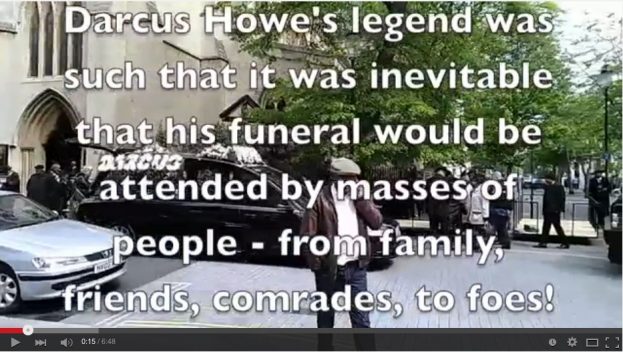

For example on April 1, Trinidadian-born Darcus Howe, a stalwart of political activism, died aged 74. Although the paperback edition of his ‘Renegade: The Life and Times of Darcus Howe’ biography published earlier this year is easily available, what an opportunity lost for young activists to learn from one of the NCMAC organisers. He was also one of two of the Mangrove Nine to brilliantly defend themselves at the celebrated 1971 Old Bailey central criminal court case brought by the police against nine Africans charged with various offences arising from a march through Notting Hill demonstrating against numerous unwarranted, racially-motivated police raids on the Mangrove restaurant and community hub.

The Mangrove Nine case became a cause célèbre. At the time it was one of the longest trials at the Old Bailey. Howe, and Altheia Jones Lecointe, were the two defendants who strategically elected for self-representation. And, in acquitting all the defendants of majority of the charges, including incitement to riot, a senior judge for the first time acknowledged in a British court “evidence of racial hatred” within the Metropolitan police – some 40 years before Lord Macpherson’s Report highlighted “institutional racism” within the Met.

Thankfully the likes of Howe’s NCMAC comrade Prof Gus John is alive, and tapping into his experience of how they negotiated with police and politicians during a politically dark period of the early 1980s, can provide useful lessons for young activists to further their cause.

Imagine what the BLM movement could achieve if its young leadership has discussions about strategies and politicking with some of the elders, such as Wadsworth? In addition to organising huge ARA marches and anti-racism concerts, he was part of the Labour Party’s Black Sections, which in the 1980s and 1990s helped many Africans and Asians to become MPs, and councillors. Other comrades such Linda Bellos, who went on to wield real power as council leader in the 1980s, is also still alive.

There are also the likes of Lee Jasper, who went from street activism to becoming London Mayor Ken Livingstone’s Senior Policy Advisor on Equalities and Policing. He’s gone back to grassroots activism, agitating against the effects of austerity policies on African and ethnic minority workers, and getting ‘black politics’ back unto the Labour Party’s agenda. Younger activists can learn from someone like him, who has dealt with racial discrimination and the police both at street level and overseen various mayoral committees dealing with London’s political and economic life.

Interestingly, there are retired African senior police officers, such as former Superintendent Dr. Leroy Logan, who was in the Metropolitan Police for 30 years and challenged discrimination from within. His knowledge of the police from the insider’s perspective could be invaluable to activists in engaging better with the police.

It’s also worth pointing out that veteran activists such as Jones Lecointe and Eddie Lecointe are still politically active. These former British Black Panther Movement members were involved in two separate key 1971 Black Power court cases at the Old Bailey. Lecointe was part of the Oval House Four, whilst Jones Lecointe was part of the Mangrove Nine – both cases were as a result of clashes with the police.

Hopefully in 2017, activists will imbibe the spirit of Sankofa, by learning from the past and the elders, combining this with the opportunities on the streets, online and the political process, in order to better challenge racism, injustice and discrimination.

Kwaku is a London-based history and music industry consultant, and community activist. You can reach him via bbmbmc@gmail.com

*African is used to describe people of African heritage, irrespective of antecedents

All photos by Kwaku