If you know the modern city, then you will know that it is at once everywhere and nowhere; both an undeniable fact of the landscape and something unlikely to be set down on an Underground map or marked by official signage. Head north and you can find it in the strip-lit glare of tutoring businesses on Tottenham High Road, or out in Hayes, heralded by green Dahabshiil signs advertising money transfer to Somalia. In the south, it is the woman clicking her way to a Thamesmead community hall, in party heels and sparkling Nigerian native wear. Or the Brixton Street preacher, imploring an ambivalent passing crowd to repent through a speaker intended for karaoke.

Black African presence can be glimpsed in the whir of seamstresses at work in tiny doorway operations off Dalston’s Ridley Road Market, smelled in the spice-prickled puff of barbecued croaker fish drifting on the Old Kent Road air and heard in the eavesdropped snippets of Nigerian Yoruba, Ghanaian Twi, Ugandan-accented, Swahili and Sierra Leonean Krio ricocheting on the street. Once, this life would have been tucked away and out of sight. Hidden in the form of private card games among turn-of-the-century Somali seamen, interwar hostels established for West African students and prayer meetings in the council flat front rooms of the 1970s. But now, it spills out and bursts forth. Now, this African London is kinetic and ever-expanding, stretching out and beyond the city’s hazy border like something that cannot be wholly contained. Not just as people but as architecture. As listed former cinemas, bingo halls, pubs and banks that now bear the names of newly planted Pentecostal churches and stand as looming monuments to a quiet sort of urban conquest. Yes, if you know the city then you will know that modern Black African presence is an inescapable reality, strewn in every corner. But look for scholarship, exploration or historical record of this life and things become a little less clear. History books about Black British settlement – whether they are the scattering of publications released throughout the latter half of the twentieth century or the swelling post-2010s wave that coincided with a broader period of reappraisal and re-education with regard to race – tend to focus on modern Africans as a subcategory of a larger Black whole; one thread woven into a predominantly

Caribbean social tapestry.

In fact, Black UK residents directly drawn from Africa have only existed in an official sense for just over 30 years. Until the 1991 census introduced ‘Black African’ as an option on its identity menu, we were not considered worthy of specific categorization. One reason for this is the simple fact of numbers: Black Africans, at that particular point in British history, did not have the same immigrant population size or cultural presence as Afro-Caribbeans. But another is that – given the nascent Black British community was generally forged in the fires of a hostile, structurally racist post-war society – political solidarity was more important than quibbling over the specific source of your Blackness. It is only in the last 40 years that ‘Black’, both as a term and a political idea, has fully ceased to apply to South Asian Brits. The thinking that created this glomming together of ethnicities is obvious enough: in the face of landlords, employers and police whose bigotry didn’t specify, a certain monolithic solidarity was vital.

But I think this phenomenon as it applies to Black Africans – namely, the surprising absence of modern Africans in many of the official chronicles of Black British life – is a by-product of something else: the wider collective attempt to move the conversation about Black settlement and presence in the UK away from the symbolic enormity of the Empire Windrush. Because, of course, beyond its status as the undoubted creation myth of Black life in the UK, this ship’s 1948 arrival was the continuation rather than the beginning of Britain’s Black immigrant narrative.

Peter Fryer’s seminal 1984 book Staying Power opens with the arresting statement that ‘There were Africans in Britain before the English came here’. The fact is that whether it was the North African soldiers who established a third-century Roman settlement near Hadrian’s Wall, the African merchants who were fixtures in Georgian London, or the Black political agitators and intellectuals who turned the metropole into their home, pulpit and playground in the 1930s, Blackness in Britain has a history and a lineage beyond the mythic mid-century arrivals that followed 1948’s British Nationality Act.

Fryer and the other historians who have stood on his shoulders – not just Staying Power but the likes of Black Tudors by Miranda Kauffman, Black Poppies by Stephen Bourne and, perhaps most impactfully, Black and British by David Olusoga – have given us an important rebuke to the postcolonial view that Black Britons are recent arrivals with no significant claim on the land. Or that they are interlopers who can simply be told to go back where they came from. ‘We are here, because you were there,’ as the British-Sri Lankan novelist A. Sivanandan put it, with enviable economy.

Yet, to my mind, this noble effort to excavate the pre-Windrush history of Black Britishness has, however inadvertently, somewhat diminished the attention paid to more recent stories. In looking further back, we perhaps miss the social shifts happening right under our noses. This is not to suggest that significant moments from the last 50 years of Black history in this country – from the trial of the Mangrove Nine and the tragic death of Stephen Lawrence to the Covid-masked social uprising of 2020 – have gone unexamined. It is rather that the breadth of Black experience, and the increasingly dominant presence of Black Africans, hasn’t always been reflected in how we look at race and Britishness today. Even Olusoga himself, right near the close of Black and British, acknowledges this point – that there has been a shift in the demography of Britain’s Black population that has not been fully recognized. The Black Africans who have come to Britain since the 1980s are, in Olusoga’s words, part of ‘a second great wave of Black migration . . . that has largely gone unnoticed’.

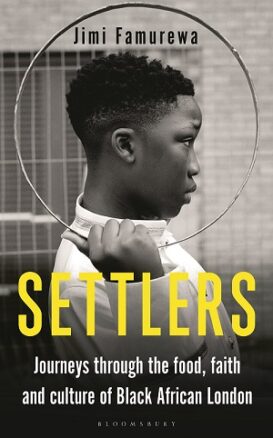

Book Settlers: Journeys through the Food, Faith and Culture of Black African London, by Jimi Famurewa is published by Bloomsbury Continuum on October 13th at £18.99.