The Politics Of Racism, Terminologies And Imagery

2023 Update: WhatsApp TikTok: #AfriphobiaAndApartheid1 Monday March 20 2023, 6.30-8.30pm GMT via Zoom. Video mashup screening and discussion. Click to book: https://bit.ly/Afriphobia1

Whilst March may be known for International Women’s Day or Month, it’s increasingly also becoming known for what’s popularly labelled March Against Racism or UN Anti-Racism Day, which is on March 21.

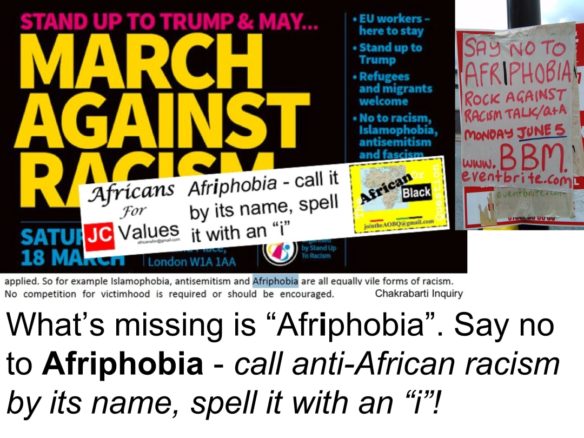

The Day, which draws big crowds to a march and rally in London and several towns and cities across Britain, has been marked since 2013 by Stand Up To Racism (SUTR), a Unite Against Fascism offshoot, which is supported by many trade unions and mainstream politicians.

I naturally applaud any initiative that fights against racism. After all, it’s Africans who bear the brunt of racism, as evidenced by social indices across unemployment, housing, school exclusions, academic attainment, pay disparity, custodial sentences, deaths in state custody, etc. Indeed, it is for this reason that the United Nations (UN) has declared 2015-24 International Decade for People of African Descent (IDPAD).

Whilst I support SUTR’s work – I have attended their conferences, demonstrations, and wearing my hat as TAOBQ (The African Or Black Question) campaign coordinator, I have also attended and posted on Youtube video coverage of some of the previous Days, I must critique how they use language in their anti-racism work.

I posit that SUTR unwittingly does Africans a disservice through the way it uses terminologies.

The UN’s official term for the Day is International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. I understand for brevity, SUTR has opted for the UN Anti-Racism Day. However, as we shall see, reconfiguring UN’s long terms into snappy terms can either diminish or even obfuscate the intention behind the observance.

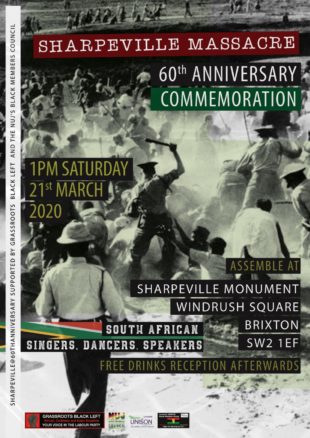

For example, you’d be hard pushed to find either in SUTR’s literature or at the London rally, that March 21 speaks to a global African experience. The UN General Assembly chose that date in 1966, because it commemorates March 21 1960, when the apartheid South African police killed 69 people at a peaceful demonstration against the apartheid pass laws in Sharpeville (see event below).

The Day is supposed to mobilise people around trying to eliminate all forms of racial discrimination. So I say if separate forms of racial discriminations are to be highlighted, as in case of anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, then shouldn’t racism specifically against Africans, which is arguably the most prevalent, also be included?

It can be argued that the very people whose lives inspired the Day are being excluded, and lumped within the catch-all ‘racism’ term, which covers all forms of racism. But then racism against Muslims and Jews are separately highlighted.

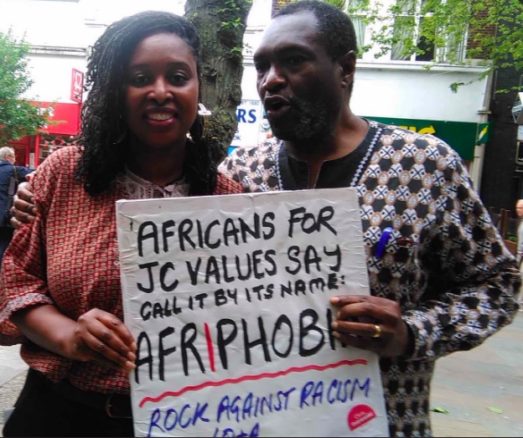

TAOBQ, and some other African-led organisations, advocate that where separate forms of racial discriminations are to be highlighted, then for the sake of equivalence, Afriphobia should be included. We define Afriphobia (spelt with an “i”) as the prejudice or discrimination against; bigotry, fear or hatred of people of African heritage and things African.

A similar definition was adopted in the recently published IDPAD Coalition UK’s document entitled ‘Documenting Afriphobia, Institutional and Structural Racism’.

Although it made its way into Labour Party’s Chakrabarti Inquiry report almost as an aside, hopefully it won’t be too long before mainstream anti-racism and left-leaning organisations start using Afriphobia within their discourse and publicity.

In the meantime African-led organisations, Global Afrikan Congress and the Black Solidarity Committee (BSC) of the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT), do not only use the Afriphobia terminology, but will also introduce 21 Days Against Racism to Britain this year.

This marking of the first 21 days of March with anti-racism activities is an initiative started in Brazil by a coalition of Brazilian-African community groups, to highlight and combat the racism faced by the biggest population of Africans outside of the African continent.

Another African-led group of politically left and trade union activists will be marking March 21 in a most appropriate manner with regards to focus and space. The focus of the event is the commemoration of the 60th anniversary of the Sharpeville Massacre – it takes place in Windrush Square, a pivotal space within the British African experience, and most importantly, it has a little-known stone monument marking the Sharpeville Massacre, which was dedicated by Lambeth Council in 1987. With South African speakers, dancers and singers on this commemoration bill, the African significance and the apartheid government and police’s racism will not be lost.

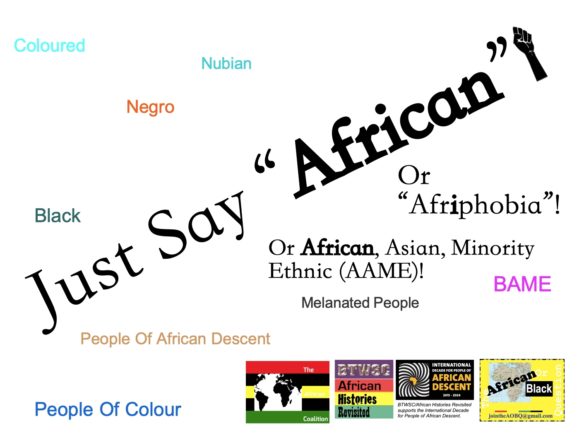

This year, TAOBQ’s campaign hashtag is #JustSayAfrican. It not only advocates the use of Afriphobia, where it’s necessary to speak specifically to anti-African racism, but also the use of African to assert our identity. Hence, whilst we are not opposed to the unifying political Black or inclusive Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) terms, we oppose the separatist Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) term.

I’m reminded of an anecdote back in the days when most London councils had funding for Black, or as some of us now call it, African History Month. Then almost everybody was Black. But when it came to Black on Black crime, everybody understood that referred only to Africans. Hence, bearing in mind that Black is generally understood to refer to Africans, we advocate the use of AAME (African, Asian and Minority Ethnic).

Thus far, I’m only aware of Tees Valley Labour AAME Forum, having embraced this term. Though I’m certain that it won’t be long before AAME gains wider currency, especially as questions are being asked about the BAME term.

With the help of African-led organisations such as IDPAD (International Decade for People of African Descent) Coalition UK, and progressive mainstream allies, we hope can get political parties such as Labour, and unions, to introduce terms such as Afriphobia and AAME into their race and racism discourse.

Language, or terms, have a power dimension. If you are not mentioned or seen, then you are not on the radar of the power brokers when it comes to allocating society’s resources. That means you can be easily marginalised. Just cast your mind to how some protected characteristics punch above their weight with regards to the disproportionate level of financial, political or media support they receive.

Also, in this age of branding and social media, visual signifiers are of utmost importance. You only have to see the rainbow colours, and you know it’s likely to speak to an LGBTQ+ issue.

But what’s the equivalent that identifies African issues? I’d like to think it’s either of the pan-African colours. But sadly, neither the red, black and green of the Universal Negro Improvement Association-African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) flag, nor the green, gold and red of the Ethiopian flag, hold much cachet outside its respective Garveyite and Rastafari followers.

As a consequence, in marking the centenary of the founding of UNIA-ACL in 2014, TAOBQ introduced the global African quad flag, which combines the four pan-African colours.

Now if you’re wondering how come you don’t know about the global African quad flag or colours, it’s because of something the African communities generally lack – organisational and lobbying clout.

A council, educational institution or corporate body doesn’t suddenly adorn itself with the rainbow colours. It takes the lobbying and politicking of LGBTQ+ campaign organisations like Stonewall for that to happen.

Incidentally, last year, a London council decided to paint some street crossings in the LGBTQ+ colours. Not surprisingly, it had the six stripes in the correct order.

For African History Month, that council decided to do the same thing, using the global African quad colours. Whilst we applaud the council for the seemingly radical move to represent the African experience in October – the four combined pan-African colours were painted in the wrong order.

Did any Africans notice, or make a fuss? All I know is that had the LGBTQ+ colours been painted in the wrong order, the LGBTQ+ community would have let the council know in no uncertain terms, and many of us would have heard about it!

That’s an illustration of proactively pushing for one’s community’s interest.

Incidentally, coming out of a recent meeting with my local council, Brent, I noticed the zebra crossing in front of the civic centre was bordered on either side with the LGBTQ+ colours. Upon reading about how that happened, I realised that the LGBTQ+ flag was also flown on top of the centre during Pride month.

So I’ll be suggesting to my council, which by the way, is the London Borough Of Culture 2020, for an equivalent treatment. That’s the crossing area gets painted in the global African quad colours, and a similar flag flies on top of the centre during African History Month – watch this space for an update.

Now, take the say “No to Islamophobia” or “No to anti-Semitism” slogans on SUTR literature. That’s in part because of Muslim and Jewish organisational support and lobbying.

But where are the African-focused representative organisations with any clout that’s engaging outside of the African communities? I’m willing to be corrected, but I can’t think of one. Until we have such an organisation or organisations, our interests are likely to continue to be overlooked or trampled upon.

Take the case of City Hall’s decision to cancel Africa In The Square – what outcry has there been? Recently, the organisers of Sankofa Day were informed that it can not take place in Trafalgar Square this year – the Day observes UN’s August 23 initiative (see below). Fair enough, an immediate community initiative called out for African supporters and media to turn up outside City Hall for a press release. But it won’t surprise you to know that the turn out was not the best. So we must not shy away from the fact that we’re are at times complicit in our own marginalisation and discrimination.

It’s also been argued that the Home Office deliberately went for “low hanging fruit” when it decided to “scoop” thousands of particularly African-Caribbean people who had lived legally in Britain for decades, in what was subsequently exposed as the Windrush Scandal, but which I call the Commonwealth and Windrush Scandal. Thankfully in this particular case, there’s now a wide network of African-led Windrush support and activist groups, campaigning and highlighting the ongoing issues.

Indeed, the need for a strong African-focused representative group is one of the topics that will be discussed at The African Coalition Day on August 15.

Talking about August, some Garveyites call it Mosiah month, in recognition of the fact that not only was Marcus Garvey born in that month, but also a number of key UNIA-ACL activities took place in that month. Such as the Negro World newspaper, which was started on Garvey’s thirty-first birthday, 17th August 1918, and the first annual Convention of the Negro Peoples of the World started in 1920 and had activities covering the whole of the month of August.

In the midst of the annual events that take place in August, there’s a Day that can disempower, obfuscate or marginalise African agency, due to the event’s name and content focus.

I’m talking about the events that mark August 23 and variously labelled Slavery Day, Slavery Memorial Day or Slavery Remembrance Day. The UN’s term for this observance, which started in 1998, is International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition. Although the 2007 government press release that announced that Britain will begin to observe this Day used the UN’s term, the parliamentary proceedings that preceded that announcement revolved around a call for a national Slavery Memorial Day.

So not surprisingly statutory bodies that observe this Day opted for one of the shortened terms. This in turn means the focus of the content is often a Eurocentric narrative which literally translates as – it was Europeans who in recognising how bad it was, fought to abolish enslavement.

Note that some of us use enslavement instead of slavery, enslaver instead of slave master, and trafficking instead of trade. Using these terms, provide a perception shift, which makes one realise, for example, that it was a deliberate act by one set of people who put another set of people into a position of enslavement.

Even though an organisation like the International Slavery Museum does some good work marking the Day, no doubt due in part to the local Liverpool African community’s engagement with the museum, the default impression given by terms like Slavery Remembrance Day, is the disempowering, victimhood and subservient position exemplified by the “Am I not a man and a brother?” imagery.

Also, there is usually nothing that speaks to the Abolition part of the Day – particularly the agency of Africans in securing the abolition of the trans-Atlantic trafficking and enslavement. Most mainstream events do not let you know that the Day is based on an important global African historic milestone – the evening of the 22nd to 23rd August 1791 marks the start of the Haitian Revolution. It’s the only successful African uprising in the Western hemisphere, which led to an independent state of Haiti on January 1 1804.

It is because of this general silence on the subject of the African’s resistance and agency in achieving Abolition, and parliament’s call for the Day “to memoralise both the outlawing of the slave trade and the resistance to it by enslaved people”, that some Africanist organisations advocate the use of the International Day Of African Resistance Against Enslavement. Because this term puts the focus on African agency, not victimhood.

I hope this gives you some idea about how the use of terms within the anti-racism space, can either empower, disempower, or marginalise us as African people.

The African Coalition Day 2020 is on Aug. 15: http://bit.ly/TheAfricanCDay

Kwaku is a history consultant, author of the ‘Look How Far We’ve Come Race/Racism Primer’ and producer of the companion ‘Look How Far We’ve Come: Commentaries On British Society And Racism?’ DVD. He is also an identity activist and TAOBQ (The African Or Black Question) co-ordinator.