Little is known of the early history of Kenya’s interior, except that peoples from all over the African continent settled here. Arab merchants established trading posts on the coast during the seventh century. The Portuguese took control of coastal trading from the early 16th century, but by 1720 they had been driven out by the Arabs. For the following century, the coastal region was ruled mainly by the Arabian Omani

Around 1750 the Masai, a people of nomadic cattle-herders whose young men formed a military elite (el morani), began entering Kenya from the north and spreading out southwards, raiding and rustling. At the end of the 1850s there were Masai by the coast near Mombasa. During the 1860s, the Masai drove back Europeans attempting to penetrate the interior of the country. Two outbreaks of cattle-disease in the 1880s, an outbreak of smallpox in 1889–90 and internecine fighting between supporters of two rival chiefs weakened the Masai considerably by the 1890s.

The British East African Company was granted a charter in 1888, which led to the colonization of present day Kenya. When the company became bankrupt the British government took over administration of the colony which they intended to use a gateway to Uganda, Buganda and Bunyoro because there were no minerals to exploit in Kenya. In order to subdue the colony, the British authorities forcibly took land, introduced forced labor and passed legislation that ensured natives became subjects of the British settlers.

The road to colonization of Kenya was difficult for the British because by the turn of the 20th century Indians outnumbered whites 2:1 and the Indian rupee was Kenya’s main currency. It is reported that there were approximately 23 000 Indians and only 10 000 whites. As a means of consolidating power, the British introduced the hut tax in 1902. A certain amount of taxes was to be paid to the government for each hut a family owned. This meant that native Kenyans had to earn money which could only be achieved by working for someone else that could pay them wages. The punishment for not paying hut tax was a fine and which often when not paid led to forced labor thereby providing the British settlers with the cheap labor they were searching for.

As demand for labor increased, British settlers then introduced poll tax which was required of every citizen in the country. In addition, Kenyans had to work for 60 days a year for the government unless they were already employed by British settlers. This led to the creation of native reservations which were often situated far from major roads and rail and whose soil was not conducive for farming. A lot of measures employed by the British settlers in Kenya were imported from South Africa and Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe).

As demand for labor increased, British settlers then introduced poll tax which was required of every citizen in the country. In addition, Kenyans had to work for 60 days a year for the government unless they were already employed by British settlers. This led to the creation of native reservations which were often situated far from major roads and rail and whose soil was not conducive for farming. A lot of measures employed by the British settlers in Kenya were imported from South Africa and Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe).

In 1913, the government passed a land bill that gave the white British settlers 999 year leases on the land and effectively created a monopoly on land use. Later, in 1919 British settlers introduced the Kipande system that required all Kenyan men to wear identity discs similar to the chitupa introduced in Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) which limited movement labor.er

The Colony and Protectorate of Kenya was established on 11 June 1920 when the territories of the former East Africa Protectorate (except those parts of that Protectorate over which His Majesty the Sultan of Zanzibar had sovereignty) were annexed by the UK. The Kenya Protectorate was established on 13 August 1920 when the territories of the former East Africa Protectorate which were not annexed by the UK were established as a British Protectorate. The Protectorate of Kenya was governed as part of the Colony of Kenya by virtue of an agreement between the United Kingdom and the Sultan dated 14 December 1895.

In the 1920s natives objected to the reservation of the White Highlands for Europeans, especially British war veterans. Bitterness grew between the natives and the Europeans. The population in 1921 was estimated at 2,376,000, of whom 9,651 were Europeans, 22,822 Indians, and 10,102 Arabs. Mombasa, the largest city in 1921, had a population of 32,000 at that time

Native Kenyan labourers were in one of three categories: squatter, contract, or casual.[C] By the end of World War I, squatters had become well established on European farms and plantations in Kenya, with Kikuyu squatters comprising the majority of agricultural workers on settler plantations. An unintended consequence of colonial rule, the squatters were targeted from 1918 onwards by a series of Resident Native Labourers Ordinances—criticised by at least some MPs —which progressively curtailed squatter rights and subordinated native Kenyan farming to that of the settlers. The Ordinance of 1939 finally eliminated squatters’ remaining tenancy rights, and permitted settlers to demand 270 days’ labour from any squatters on their land. and, after World War II, the situation for squatters deteriorated rapidly, a situation the squatters resisted fiercely.

In the early 1920s, though, despite the presence of 100,000 squatters and tens of thousands more wage labourers, there was still not enough native Kenyan labour available to satisfy the settlers’ needs. The colonial government duly tightened the measures to force more Kenyans to become low-paid wage-labourers on settler farms.

You may travel through the length and breadth of Kitui Reserve and you will fail to find in it any enterprise, building, or structure of any sort which Government has provided at the cost of more than a few sovereigns for the direct benefit of the natives.

The place was little better than a wilderness when I first knew it 25 years ago, and it remains a wilderness to-day as far as our efforts are concerned. If we left that district to-morrow the only permanent evidence of our occupation would be the buildings we have erected for the use of our tax-collecting staff.

—Chief Native Commissioner of Kenya, 1925

The colonial government used the measures brought in as part of its land expropriation and labour ‘encouragement’ efforts to craft the third plank of its growth strategy for its settler economy: subordinating African farming to that of the Europeans. Nairobi also assisted the settlers with rail and road networks, subsidies on freight charges, agricultural and veterinary services, and credit and loan facilities. The near-total neglect of native farming during the first two decades of European settlement was noted by the East Africa Commission.

The resentment of colonial rule would not have been decreased by the wanting provision of medical services for native Kenyans, nor by the fact that in 1923, for example, “the maximum amount that could be considered to have been spent on services provided exclusively for the benefit of the native population was slightly over one-quarter of the taxes paid by them”. The tax burden on Europeans in the early 1920s, meanwhile, was very light. Interwar infrastructure-development was also largely paid for by the indigenous population.

Kenyan employees were often poorly treated by their European employers, with some settlers arguing that native Kenyans “were as children and should be treated as such”. Some settlers flogged their servants for petty offences. To make matters even worse, native Kenyan workers were poorly served by colonial labour-legislation and a prejudiced legal-system. The vast majority of Kenyan employees’ violations of labour legislation were settled with “rough justice” meted out by their employers. Most colonial magistrates appear to have been unconcerned by the illegal practice of settler-administered flogging; indeed, during the 1920s, flogging was the magisterial punishment-of-choice for native Kenyan convicts. The principle of punitive sanctions against workers was not removed from the Kenyan labour statutes until the 1950s.

Mau Mau Uprising

The Mau Mau Uprising (1952–1960), also known as the Mau Mau Rebellion, the Kenya Emergency, and the Mau Mau Revolt, was a war in the British Kenya Colony (1920–1963) between the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA), also known as Mau Mau, and the British authorities.

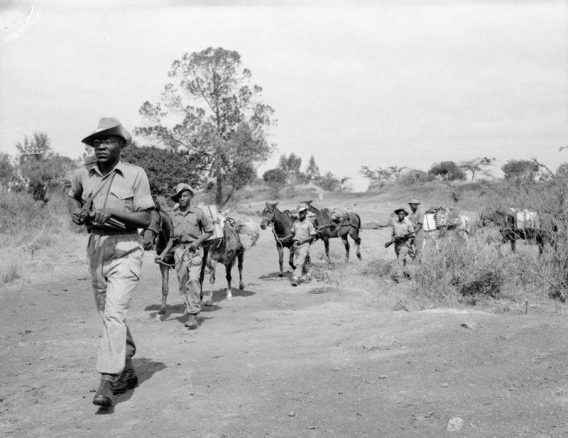

Dominated by the Kikuyu people, Meru people and Embu people, the KLFA also comprised units of Kamba and Maasai peoples who fought against the white European colonist-settlers in Kenya, the British Army, and the local Kenya Regiment (British colonists, local auxiliary militia, and pro-British Kikuyu people).

The capture of rebel leader, Field Marshal Dedan Kimathi, on 21 October 1956, signalled the defeat of the Mau Mau However, the rebellion survived until after Kenya’s independence from Britain, driven mainly by the Meru units led by Field Marshal Musa Mwariama and General Baimungi. Baimuingi, one of the last Mau Mau generals, was killed shortly after Kenya attained self-rule.

The KLFA failed to capture widespread public support. Frank Füredi, in The Mau Mau War in Perspective suggests this was due to a British policy of divide and rule but fails to cite any contemporary British government documents which support this assertion. General Sir Frank Kitson, who served in the British colonial forces in Kenya, authored a book entitled Gangs and Counter-gangs in which he describes the tactic of manipulating the Mau Maus into rival gangs and pitting them against one another. The Mau Mau movement remained internally divided, despite attempts to unify the factions. The British, meanwhile, applied the strategy and tactics they developed in suppressing the Malayan Emergency (1948–60). The Mau Mau Uprising created a rift between the European colonial community in Kenya and the metropole,[ and also resulted in violent divisions within the Kikuyu community Suppressing the Mau Mau Uprising in the Kenyan colony cost Britain £55 million and caused at least 11,000 deaths among the Mau Mau and other forces, with some estimates considerably higher. This included 1,090 executions at the end of the war, the largest wartime use of capital punishment by the British Empire.

The origin of the term Mau Mau

The origin of the term Mau Mau is uncertain. According to some members of Mau Mau, they never referred to themselves as such, instead preferring the military title Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA). Some publications, such as Fred Majdalany’s State of Emergency: The Full Story of Mau Mau, claim it was an anagram of Uma Uma (which means “get out get out”) and was a military codeword based on a secret language-game Kikuyu boys used to play at the time of their circumcision. Majdalany also says the British simply used the name as a label for the Kikuyu ethnic community without assigning any specific definition.

Akamba people say the name Mau Mau came from ‘ Ma Umau’ meaning ‘Our Grandfathers’. The term was first used during a pastoralists revolt against de-stocking that took place in 1938 led by Muindi Mbingu during which he urged the colonists to leave Kenya so that his people (the kamba) could live freely like the time of ‘Our Grandfathers’ (Twenda kwikala ta maau mau maitu, tuithye ngombe ta Maau mau maitu, nundu nthi ino ni ya maau mau maitu).

As the movement progressed, a Swahili backronym was adopted: “Mzungu Aende Ulaya, Mwafrika Apate Uhuru” meaning “Let the foreigner go back abroad, let the African regain independence”.J.M. Kariuki, a member of Mau Mau who was detained during the conflict, suggests the British preferred to use the term Mau Mau instead of KLFA to deny the Mau Mau rebellion international legitimacy. Kariuki also wrote that the term Mau Mau was adopted by the rebellion in order to counter what they regarded as colonial propaganda.

Another possible origin is a mishearing of the Kikuyu word for oath: “muuma”.

Author and activist Wangari Maathai indicates that, to her, the most interesting story of the origin of the name is the Kikuyu phrase for the beginning of a list. When beginning a list in Kikuyu, you say, “maũndũ ni mau” – “the main issues are…” and hold up three fingers to introduce them. Maathai says the three issues for the Mau Mau were land, freedom, and self-governance.

Mau Mau warfare

Mau Mau were the militant wing of a growing clamour for political representation and freedom in Kenya. The first attempt to form a countrywide political party began on 1 October 1944. This fledgling organisation was called the Kenya African Study Union. Harry Thuku was the first chairman, but he soon resigned. There is dispute over Thuku’s reason for leaving KASU: Bethwell Ogot says Thuku “found the responsibility too heavy”; David Anderson states that “he walked out in disgust” as the militant section of KASU took the initiative. KASU changed its name to the Kenya African Union (KAU) in 1946. Author Wangari Maathai writes that many of the organizers were ex-soldiers who fought for the British in Ceylon, Somalia, and Burma during the second World War. When they returned to Kenya, they were never paid and did not receive recognition for their service, whereas their British counterparts were awarded medals and received land, sometimes from the Kenyan veterans.

The failure of KAU to attain any significant reforms or redress of grievances from the colonial authorities shifted the political initiative to younger and more militant figures within the native Kenyan trade union movement, among the squatters on the settler estates in the Rift Valley and in KAU branches in Nairobi and the Kikuyu districts of central province. Around 1943, residents of Olenguruone Settlement radicalised the traditional practice of oathing, and extended oathing to women and children. By the mid-1950s, 90% of Kikuyu, Embu and Meru were oathed. On 3 October 1952, Mau Mau claimed their first European victim when they stabbed a woman to death near her home in Thika. Six days later, on 9 October, Senior Chief Waruhiu was shot dead in broad daylight in his car, which was an important blow against the colonial government. Waruhiu had been one of the strongest supporters of the British presence in Kenya. His assassination gave Baring the final impetus to request permission from the Colonial Office to declare a State of Emergency.

The Mau Mau attacks were mostly well organised and planned.

…the insurgents’ lack of heavy weaponry and the heavily entrenched police and Home Guard positions meant that Mau Mau attacks were restricted to nighttime and where loyalist positions were weak. When attacks did commence they were fast and brutal, as insurgents were easily able to identify loyalists because they were often local to those communities themselves. The Lari massacre was by comparison rather outstanding and in contrast to regular Mau Mau strikes which more often than not targeted only loyalists without such massive civilian casualties. “Even the attack upon Lari, in the view of the rebel commanders was strategic and specific.”

The Mau Mau command, contrary to the Home Guard who were stigmatised as “the running dogs of British Imperialism”, were relatively well educated. General Gatunga had previously been a respected and well read Christian teacher in his local Kikuyu community. He was known to meticulously record his attacks in a series of five notebooks, which when executed were often swift and strategic, targeting loyalist community leaders he had previously known as a teacher,

The Mau Mau military strategy was mainly guerrilla attacks launched under the cover of dark. They used stolen weapons such as guns, as well as weapons such as machetes and bows and arrows in their attacks. In a few limited cases, they also deployed biological weapons.

Women formed a core part of the Mau Mau, especially in maintaining supply lines. Initially able to avoid the suspicion, they moved through colonial spaces and between Mau Mau hideouts and strongholds, to deliver vital supplies and services to guerrilla fighters including food, ammunition, medical care, and of course, information. An unknown number also fought in the war, with the most high-ranking being Field Marshal Muthoni

British reaction

The British and international view was that Mau Mau was a savage, violent, and depraved tribal cult, an expression of unrestrained emotion rather than reason. Mau Mau was “perverted tribalism” that sought to take the Kikuyu people back to “the bad old days” before British rule. The official British explanation of the revolt did not include the insights of agrarian and agricultural experts, of economists and historians, or even of Europeans who had spent a long period living amongst the Kikuyu such as Louis Leakey. Not for the first time, the British instead relied on the purported insights of the ethnopsychiatrist; with Mau Mau, it fell to Dr. John Colin Carothers to perform the desired analysis. This ethnopsychiatric analysis guided British psychological warfare, which painted Mau Mau as “an irrational force of evil, dominated by bestial impulses and influenced by world communism”, and the later official study of the uprising, the Corfield Report.

The psychological war became of critical importance to military and civilian leaders who tried to “emphasise that there was in effect a civil war, and that the struggle was not black versus white”, attempting to isolate Mau Mau from the Kikuyu, and the Kikuyu from the rest of the colony’s population and the world outside. In driving a wedge between Mau Mau and the Kikuyu generally, these propaganda efforts essentially played no role, though they could apparently claim an important contribution to the isolation of Mau Mau from the non-Kikuyu sections of the population.

By the mid-1960s, the view of Mau Mau as simply irrational activists was being challenged by memoirs of former members and leaders that portrayed Mau Mau as an essential, if radical, component of African nationalism in Kenya and by academic studies that analysed the movement as a modern and nationalist response to the unfairness and oppression of colonial domination.

There continues to be vigorous debate within Kenyan society and among the academic community within and without Kenya regarding the nature of Mau Mau and its aims, as well as the response to and effects of the uprising. Nevertheless, partly because as many Kikuyu fought against Mau Mau on the side of the colonial government as joined them in rebellion, the conflict is now often regarded in academic circles as an intra-Kikuyu civil war, a characterisation that remains extremely unpopular in Kenya. Kenyatta described the conflict in his memoirs as a civil war rather than a rebellion. The reason that the revolt was majorly limited to the Kikuyu people was, in part, that they had suffered the most as a result of the negative aspects of British colonialism.

Wunyabari O. Maloba regards the rise of the Mau Mau movement as “without doubt, one of the most important events in recent African history.” David Anderson, however, considers Maloba’s and similar work to be the product of “swallowing too readily the propaganda of the Mau Mau war”, noting the similarity between such analysis and the “simplistic” earlier studies of Mau Mau. This earlier work cast the Mau Mau war in strictly bipolar terms, “as conflicts between anti-colonial nationalists and colonial collaborators”. Caroline Elkins’ 2005 study, Imperial Reckoning, has met similar criticism, as well as being criticised for sensationalism.

Broadly speaking, throughout Kikuyu history, there have been two traditions: moderate-conservative and radical. Despite the differences between them, there has been a continuous debate and dialogue between these traditions, leading to a great political awareness among the Kikuyu By 1950, these differences, and the impact of colonial rule, had given rise to three native Kenyan political blocks: conservative, moderate nationalist and militant nationalist. It has also been argued that Mau Mau was not explicitly national, either intellectually or operationally.

Bruce Berman argues that, “While Mau Mau was clearly not a tribal activism seeking a return to the past, the answer to the question of ‘was it nationalism?’ must be yes and no. As the Mau Mau rebellion wore on, the violence forced the spectrum of opinion within the Kikuyu, Embu and Meru to polarise and harden into the two distinct camps of loyalist and Mau Mau. This neat division between loyalists and Mau Mau was a product of the conflict, rather than a cause or catalyst of it, with the violence becoming less ambiguous over time, in a similar manner to other situation

British reaction to the uprising

—David Anderson

Philip Mitchell retired as Kenya’s governor in summer 1952, having turned a blind eye to Mau Mau’s increasing activity. Through the summer of 1952, however, Colonial Secretary Oliver Lyttelton in London received a steady flow of reports from Acting Governor Henry Potter about the escalating seriousness of Mau Mau violence, but it was not until the later part of 1953 that British politicians began to accept that the rebellion was going to take some time to deal with. At first, the British discounted the Mau Mau rebellion because of their own technical and military superiority, which encouraged hopes for a quick victory.

The British army accepted the gravity of the uprising months before the politicians, but its appeals to London and Nairobi were ignored. On 30 September 1952, Evelyn Baring arrived in Kenya to permanently take over from Potter; Baring was given no warning by Mitchell or the Colonial Office about the gathering maelstrom into which he was stepping.

Aside from military operations against Mau Mau fighters in the forests, the British attempt to defeat the movement broadly came in two stages: the first, relatively limited in scope, came during the period in which they had still failed to accept the seriousness of the revolt; the second came afterwards. During the first stage, the British tried to decapitate the movement by declaring a State of Emergency before arresting 180 alleged Mau Mau leaders (see Operation Jock Scott below) and subjecting six of them to a show trial (the Kapenguria Six); the second stage began in earnest in 1954, when they undertook a series of major economic, military and penal initiatives.

The second stage had three main planks: a large military-sweep of Nairobi leading to the internment of tens of thousands of the city’s suspected Mau Mau members and sympathisers (see Operation Anvil below); the enacting of major agrarian reform (the Swynnerton Plan); and the institution of a vast villagisation programme for more than a million rural Kikuyu (see below). In 2012, the UK government accepted that prisoners had suffered “torture and ill-treatment at the hands of the colonial administration”.

The harshness of the British response was inflated by two factors. First, the settler government in Kenya was, even before the insurgency, probably the most openly racist one in the British empire, with the settlers’ violent prejudice attended by an uncompromising determination to retain their grip on power and half-submerged fears that, as a tiny minority, they could be overwhelmed by the indigenous population. Its representatives were so keen on aggressive action that George Erskine referred to them as “the White Mau Mau”. Second, the brutality of Mau Mau attacks on civilians made it easy for the movement’s opponents—including native Kenyan and loyalist security forces—to adopt a totally dehumanised view of Mau Mau adherents.

A variety of persuasive techniques were initiated by the colonial authorities to punish and break Mau Mau’s support: Baring ordered punitive communal-labour, collective fines and other collective punishments, and further confiscation of land and property. By early 1954, tens of thousands of head of livestock had been taken, and were allegedly never returned. Detailed accounts of the policy of seizing livestock from Kenyans suspected of supporting Mau Mau rebels were finally released in April 2012

State of emergency declared

On 20 October 1952, Governor Baring signed an order declaring a state of emergency. Early the next morning, Operation Jock Scott was launched: the British carried out a mass-arrest of Jomo Kenyatta and 180 other alleged Mau Mau leaders within Nairobi. Jock Scott did not decapitate the movement’s leadership as hoped, since news of the impending operation was leaked. Thus, while the moderates on the wanted list awaited capture, the real militants, such as Dedan Kimathi and Stanley Mathenge (both later principal leaders of Mau Mau’s forest armies), fled to the forests.

The day after the round up, another prominent loyalist chief, Nderi, was hacked to pieces, and a series of gruesome murders against settlers were committed throughout the months that followed. The violent and random nature of British tactics during the months after Jock Scott served merely to alienate ordinary Kikuyu and drive many of the wavering majority into Mau Mau’s arms.Three battalions of the King’s African Rifles were recalled from Uganda, Tanganyika and Mauritius, giving the regiment five battalions in all in Kenya, a total of 3,000 native Kenyan troops. To placate settler opinion, one battalion of British troops, from the Lancashire Fusiliers, was also flown in from Egypt to Nairobi on the first day of Operation Jock Scott.In November 1952, Baring requested assistance from the Security Service. For the next year, the Service’s A.M. MacDonald would reorganise the Special Branch of the Kenya Police, promote collaboration with Special Branches in adjacent territories, and oversee coordination of all intelligence activity “to secure the intelligence Government requires”.

—Percy Sillitoe, Director General of MI5

Letter to Evelyn Baring, 9 January 1953

In January 1953, six of the most prominent detainees from Jock Scott, including Kenyatta, were put on trial, primarily to justify the declaration of the Emergency to critics in London. The trial itself was claimed to have featured a suborned lead defence-witness, a bribed judge, and other serious violations of the right to a fair trial.

Native Kenyan political activity was permitted to resume at the end of the military phase of the Emergency.

Military operations

The onset of the Emergency led hundreds, and eventually thousands, of Mau Mau adherents to flee to the forests, where a decentralised leadership had already begun setting up platoons. The primary zones of Mau Mau military strength were the Aberdares and the forests around Mount Kenya, whilst a passive support-wing was fostered outside these areas. Militarily, the British defeated Mau Mau in four years (1952–56) using a more expansive version of “coercion through exemplary force”. In May 1953, the decision was made to send General George Erskine to oversee the restoration of order in the colony.

By September 1953, the British knew the leading personalities in Mau Mau, and the capture and 68 hour interrogation of General China on 15 January the following year provided a massive intelligence boost on the forest fighters. Erskine’s arrival did not immediately herald a fundamental change in strategy, thus the continual pressure on the gangs remained, but he created more mobile formations that delivered what he termed “special treatment” to an area. Once gangs had been driven out and eliminated, loyalist forces and police were then to take over the area, with military support brought in thereafter only to conduct any required pacification operations. After their successful dispersion and containment, Erskine went after the forest fighters’ source of supplies, money and recruits, i.e. the native Kenyan population of Nairobi. This took the form of Operation Anvil, which commenced on 24 April 1954.

Operation Anvil

By 1954, Nairobi was regarded as the nerve centre of Mau Mau operations. The insurgents in the highlands of the Abedares and Mt Kenya were being supplied provisions and weapons by supporters in Nairobi via couriers. Anvil was the ambitious attempt to eliminate Mau Mau’s presence within Nairobi in one fell swoop. 25,000 members of British security forces under the control of General George Erskine were deployed as Nairobi was sealed off and underwent a sector-by-sector purge. All native Kenyans were taken to temporary barbed-wire enclosures, whereafter those who were not Kikuyu, Embu or Meru were released; those who were remained in detention for screening.

Whilst the operation itself was conducted by Europeans, most suspected members of Mau Mau were picked out of groups of the Kikuyu-Embu-Meru detainees by a native Kenyan informer. Male suspects were then taken off for further screening, primarily at Langata Screening Camp, whilst women and children were readied for ‘repatriation’ to the reserves (many of those slated for deportation had never set foot in the reserves before). Anvil lasted for two weeks, after which the capital had been cleared of all but certifiably loyal Kikuyu; 20,000 Mau Mau suspects had been taken to Langata, and 30,000 more had been deported to the reserves.

Villagisation programme

—District Commissioner of Nyeri

If military operations in the forests and Operation Anvil were the first two phases of Mau Mau’s defeat, Erskine expressed the need and his desire for a third and final phase: cut off all the militants’ support in the reserves.[188] The means to this terminal end was originally suggested by the man brought in by the colonial government to do an ethnopsychiatric ‘diagnosis’ of the uprising, JC Carothers: he advocated a Kenyan version of the villagisation programmes that the British were already using in places like Malaya.

So it was that in June 1954, the War Council took the decision to undertake a full-scale forced-resettlement programme of Kiambu, Nyeri, Murang’a and Embu Districts to cut off Mau Mau’s supply lines. Within eighteen months, 1,050,899 Kikuyu in the reserves were inside 804 villages consisting of some 230,000 huts. The government termed them “protected villages”, purportedly to be built along “the same lines as the villages in the North of England” though the term was actually a “euphemism[] for the fact that hundreds of thousands of civilians were corralled, often against their will, into settlements behind barbed-wire fences and watch towers.

While some of these villages were to protect loyalist Kikuyu, “most were little more than concentration camps to punish Mau Mau sympathizers.” The villagisation programme was the coup de grâce for Mau Mau. By the end of the following summer, Lieutenant General Lathbury no longer needed Lincoln bombers for raids because of a lack of targets, and, by late 1955, Lathbury felt so sure of final victory that he reduced army forces to almost pre-Mau Mau levels.

He noted, however, that the British should have “no illusions about the future. Mau Mau has not been cured: it has been suppressed. The thousands who have spent a long time in detention must have been embittered by it. Nationalism is still a very potent force and the African will pursue his aim by other means. Kenya is in for a very tricky political future.”

—Council of Kenya-Colony’s Ministers, July 1954

The government’s public relations officer, Granville Roberts, presented villagisation as a good opportunity for rehabilitation, particularly of women and children, but it was, in fact, first and foremost designed to break Mau Mau and protect loyalist Kikuyu, a fact reflected in the extremely limited resources made available to the Rehabilitation and Community Development Department. Refusal to move could be punished with the destruction of property and livestock, and the roofs were usually ripped off of homes whose occupants demonstrated reluctance.] Villagisation also solved the practical and financial problems associated with a further, massive expansion of the Pipeline programme, and the removal of people from their land hugely assisted the enaction of Swynnerton Plan.

The villages were surrounded by deep, spike-bottomed trenches and barbed wire, and the villagers themselves were watched over by members of the Home Guard, often neighbours and relatives. In short, rewards or collective punishments such as curfews could be served much more readily after villagisation, and this quickly broke Mau Mau’s passive wing. Though there were degrees of difference between the villages, the overall conditions engendered by villagisation meant that, by early 1955, districts began reporting starvation and malnutrition. One provincial commissioner blamed child hunger on parents deliberately withholding food, saying the latter were aware of the “propaganda value of apparent malnutrition”

four months after the institution of villagisation

The Red Cross helped mitigate the food shortages, but even they were told to prioritise loyalist areas.[202] The Baring government’s medical department issued reports about “the alarming number of deaths occurring amongst children in the ‘punitive’ villages”, and the “political” prioritisation of Red Cross relief.[202]

One of the colony’s ministers blamed the “bad spots” in Central Province on the mothers of the children for “not realis[ing] the great importance of proteins”, and one former missionary reported that it “was terribly pitiful how many of the children and the older Kikuyu were dying. They were so emaciated and so very susceptible to any kind of disease that came along”.[182] Of the 50,000 deaths which John Blacker attributed to the Emergency, half were children under the age of ten.[204]

The lack of food did not just affect the children, of course. The Overseas Branch of the British Red Cross commented on the “women who, from progressive undernourishment, had been unable to carry on with their work”.[205]

Disease prevention was not helped by the colony’s policy of returning sick detainees to receive treatment in the reserves,[206] though the reserves’ medical services were virtually non-existent, as Baring himself noted after a tour of some villages in June 1956.[207]

[edit]

Kenyans were granted nearly[208] all of the demands made by the KAU in 1951.

On 18 January 1955, the Governor-General of Kenya, Evelyn Baring, offered an amnesty to Mau Mau activists. The offer was that they would not face prosecution for previous offences, but may still be detained. European settlers were appalled at the leniency of the offer. On 10 June 1955 with no response forthcoming, the offer of amnesty to the Mau Mau was revoked.

In June 1956, a programme of land reform increased the land holdings of the Kikuyu.[209][citation needed]. This was coupled with a relaxation of the ban on native Kenyans growing coffee, a primary cash crop.[209][citation needed]

In the cities the colonial authorities decided to dispel tensions by raising urban wages, thereby strengthening the hand of moderate union organisations like the KFRTU. By 1956, the British had granted direct election of native Kenyan members of the Legislative Assembly, followed shortly thereafter by an increase in the number of local seats to fourteen. A Parliamentary conference in January 1960 indicated that the British would accept “one person—one vote” majority rule.

Deaths

The number of deaths attributable to the Emergency is disputed. David Anderson estimates 25,000[19] people died; British demographer John Blacker’s estimate is 50,000 deaths—half of them children aged ten or below. He attributes this death toll mostly to increased malnutrition, starvation and disease from wartime conditions.[204]

Caroline Elkins says “tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands” died.[210] Elkins numbers have been challenged by Blacker, who demonstrated in detail that her numbers were overestimated, explaining that Elkins’ figure of 300,000 deaths “implies that perhaps half of the adult male population would have been wiped out—yet the censuses of 1962 and 1969 show no evidence of this—the age-sex pyramids for the Kikuyu districts do not even show indentations.”[204]

His study dealt directly with Elkins’ claim that “somewhere between 130,000 and 300,000 Kikuyu are unaccounted for” at the 1962 census,[211] and was read by both David Anderson and John Lonsdale prior to publication.[3] David Elstein has noted that leading authorities on Africa have taken issue with parts of Elkins’ study, in particular her mortality figures: “The senior British historian of Kenya, John Lonsdale, whom Elkins thanks profusely in her book as ‘the most gifted scholar I know’, warned her to place no reliance on anecdotal sources, and regards her statistical analysis—for which she cites him as one of three advisors—as ‘frankly incredible’.”[3]

The British possibly killed more than 20,000 Mau Mau militants,[4] but in some ways more notable is the smaller number of Mau Mau suspects dealt with by capital punishment: by the end of the Emergency, the total was 1,090. At no other time or place in the British empire was capital punishment dispensed so liberally—the total is more than double the number executed by the French in Algeria.[212]

Author Wangari Maathai indicates that more than one hundred thousand Africans, mostly Kikuyus, may have died in the concentration camps and emergency villages.[213]

Officially 1,819 Native Kenyans were killed by the Mau Mau. David Anderson believes this to be an undercount and cites a higher figure of 5,000 killed by the Mau Mau.[3][5]

War crimes

War crimes have been broadly defined by the Nuremberg principles as “violations of the laws or customs of war”, which includes massacres, bombings of civilian targets, terrorism, mutilation, torture, and murder of detainees and prisoners of war. Additional common crimes include theft, arson, and the destruction of property not warranted by military necessity.

David Anderson’s says the rebellion was “a story of atrocity and excess on both sides, a dirty war from which no one emerged with much pride, and certainly no glory.” Political scientist Daniel Goldhagen describes the campaign against the Mau Mau as an example of eliminationism, though this verdict has been fiercely criticised.

British war crimes

The British authorities suspended civil liberties in Kenya. Many Kikuyu were forced to move. Between 320,000 and 450,000 of them were interned.. Most of the rest – more than a million – were held in “enclosed villages” also known as concentration camps. Although some were Mau Mau guerrillas, most were victims of collective punishment that colonial authorities imposed on large areas of the country. Hundreds of thousands were beaten or sexually assaulted to extract information about the Mau Mau threat. Later, prisoners suffered even worse mistreatment in an attempt to force them to renounce their allegiance to the insurgency and to obey commands. Prisoners were questioned with the help of “slicing off ears, boring holes in eardrums, flogging until death, pouring paraffin over suspects who were then set alight, and burning eardrums with lit cigarettes”. Castration by British troops and denying access to medical aid to the detainees were also widespread and common.[217][218][219] Among the detainees who suffered severe mistreatment was Hussein Onyango Obama, the grandfather of Barack Obama, the former President of the United States. According to his widow, British soldiers forced pins into his fingernails and buttocks and squeezed his testicles between metal rods and two others were castrated.[220]

The historian Robert Edgerton describes the methods used during the emergency: “If a question was not answered to the interrogator’s satisfaction, the subject was beaten and kicked. If that did not lead to the desired confession, and it rarely did, more force was applied. Electric shock was widely used, and so was fire. Women were choked and held under water; gun barrels, beer bottles, and even knives were thrust into their vaginas. Men had beer bottles thrust up their rectums, were dragged behind Land Rovers, whipped, burned and bayoneted… Some police officers did not bother with more time-consuming forms of torture; they simply shot any suspect who refused to answer, then told the next suspect, to dig his own grave. When the grave was finished, the man was asked if he would now be willing to talk.”[221]

—Caroline Elkins

In June 1957, Eric Griffith-Jones, the attorney general of the British administration in Kenya, wrote to the governor, Evelyn Baring, 1st Baron Howick of Glendale, detailing the way the regime of abuse at the colony’s detention camps was being subtly altered. He said that the mistreatment of the detainees is “distressingly reminiscent of conditions in Nazi Germany or Communist Russia“. Despite this, he said that in order for abuse to remain legal, Mau Mau suspects must be beaten mainly on their upper body, “vulnerable parts of the body should not be struck, particularly the spleen, liver or kidneys”, and it was important that “those who administer violence … should remain collected, balanced and dispassionate”. He also reminded the governor that “If we are going to sin”, he wrote, “we must sin quietly.”[220][223]

Author Wangari Maathai indicates that in 1954, three out of every four Kikuyu men were in detention, and that land was taken from detainees and given to collaborators. Detainees were pushed into forced labor. Maathai also notes that the Home Guard were especially known to rape women. The Home Guard’s reputation for cruelty in the form of terror and intimidation was well known, whereas the Mau Mau soldiers were initially respectful of women.[224]

Chuka Massacre[edit]

The Chuka Massacre, which happened in Chuka, Kenya, was perpetrated by members of the King’s African Rifles B Company in June 1953 with 20 unarmed people killed during the Mau Mau uprising. Members of the 5th KAR B Company entered the Chuka area on 13 June 1953, to flush out rebels suspected of hiding in the nearby forests. Over the next few days, the regiment had captured and executed 20 people suspected of being Mau Mau fighters for unknown reasons. The people executed belonged to the Kikuyu Home Guard — a loyalist militia recruited by the British to fight the guerrillas. Nobody ever stood trial for the massacre.[225]

Hola massacre[edit]

The Hola massacre was an incident during the conflict in Kenya against British colonial rule at a colonial detention camp in Hola, Kenya. By January 1959, the camp had a population of 506 detainees, of whom 127 were held in a secluded “closed camp”. This more remote camp near Garissa, eastern Kenya, was reserved for the most uncooperative of the detainees. They often refused, even when threats of force were made, to join in the colonial “rehabilitation process” or perform manual labour or obey colonial orders. The camp commandant outlined a plan that would force 88 of the detainees to bend to work. On 3 March 1959, the camp commandant put this plan into action – as a result, 11 detainees were clubbed to death by guards.[226] 77 surviving detainees sustained serious permanent injuries.[227] The British government accepts that the colonial administration tortured detainees, but denies liability.[228]