When we examine how racial ideas were produced and circulated in Britain, however, it becomes ever more apparent that racism was ‘sold’ to the British public by entertainers, showbiz managers, writers and prospectors. Seeking to profit from curious minds, the presentation of racial difference became a means to project Britain’s ‘greatness’ to the nation at large. But to be a Great Briton, one would have to be white. Underpinned by pseudo-scientific theories, the belief in a hierarchy of races permeated the economic and social fabric of the 19th Century. Fused with a popular interest in the natural world and human biology, it found forceful expression in a curious practice which played a critical role in disseminating racist ideology: human exhibitions.

Human displays were popular throughout the 19th Century, and grew in scale as the century progressed. Billed as ‘authentic’ encounters with (mostly) black African peoples, exhibitors tapped into a pervading fascination with cultural otherness. They intended to provide patrons with an ‘experience’ of African life; the people on display were instructed to perform tribal customs and ceremonies, often to a timetable that would be advertised in advance. Whilst differentiating displayed peoples from resident ethnic minorities in Britain was critical to maintaining popular interest, there was no question that they served to reaffirm white British supremacy over ‘lesser’ peoples.

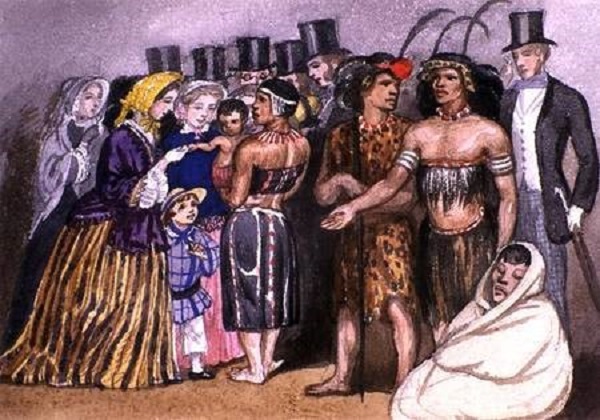

The 1853 exhibition of ‘Native Zulu Kafirs’ at St George’s Gallery in Hyde Park Corner was hugely significant – not least because of the amount of publicity material it generated (even Charles Dickens visited), but because it occurred at a critical moment in British history. The party of thirteen Zulus (eleven men, one woman and a child) had been imported by merchant A. T. Caldecott and his son, Charles Henry. Held just two years after the 1851 Great Exhibition, the display of ‘Zulu Kafirs’ capitalised upon interest in Britain’s imperial project. It would be of ‘intrinsic interest’, Charles Henry suggested, because the British had been involved in a long conflict with people ‘of the same class although not of the same tribe’ in South Africa. Made politically relevant by Caldecott, the exhibition was hugely successful, running for four months before embarking on a national tour.

That the spectacle was intended to substantiate theories of racial hierarchy is difficult to discern, but it is clear that it helped to fuel popular ideas pertaining to racial superiority which. Take note, for instance, of a review published in Lady’s Newspaper on 21st May 1853:

From his [Caldecott’s] description of the Zulus, a residence among them must be anything but agreeable; for though they are hospitable, and much given to song and dance of the sort, they have an awkward habit of cracking skulls on the slightest provocation, or, just as often, on no provocation at all, which would seem to make a native Zulu something like old Lambro, “a good friend, but bad acquaintance.”.

The treatment of performers ‘off stage’ also provides an insight into the intentions of the show and its manager. On 29th September 1853, The Times reported that Chief Nkaloocooloo was brought before a magistrate charged with assaulting Charles Caldecott. The previous day, the chief had been walking in Hyde Park with four others from his party. Soon after leaving, Caldecott had asked them to return to their residence, and insisted they did so under the escort of a policeman. Upon arriving at the gallery, the group refused to go inside, and a crowd soon gathered as Caldecott attempted to manhandle the chief indoors. The ‘impertinent’ chief responded by striking Caldecott on the shoulder. Soon after being restrained, the chief was given into custody.

The Zulu Kafirs at the St. George’s Gallery, Illustrated London News, May 28, 1853,In court the following day, the chief was asked by the magistrate if Caldecott had reason to request that the Zulu party return to their residence. The chief denied Caldecott had a right to do so, stating through an interpreter that he had been employed merely to perform ‘all native dances and other customs as required for the purposes of exhibition’. Caldecott’s response is enlightening. ‘If they [the displayed peoples] were permitted to go abroad at their own pleasures without control’, he said, ‘the consequences to the public might be most serious’. Whilst the magistrate dismissed Caldecott’s jurisdiction over the freedom of movement of his charges, the belief that he could exercise such control suggests that exhibitors were anxious to maintain fairly narrow parameters for racial interaction. By ensuring that behaviour of non-white exhibits was for observation only, Caldecott’s actions indicate that white superiority over people of African heritage had become a key feature of the national self-image.

The role of human exhibitions in shaping engagement with different cultures and races was clearly a powerful one. If we come to understand their power and influence upon a viewing audience, we begin to appreciate that the dynamics of racism in Britain owed much to a carefully stage-managed interaction between black people and white people, all with an intention to assert white cultural dominance. By the end of the century, displayed peoples were being imported in their hundreds to live in purpose-built ‘native villages’ under the aegis of world fairs. By the time of Frank Fillis’s Savage South Africa exhibition at Earl’s Court in 1899 (for which Fillis imported 200 people from various native groups, in addition to exotic animals for authenticity), the rationale for human exhibitions had become rooted in racial condescension. Is it any wonder, then, that opportunities for black people living in Britain increasingly began to conform with the notion of ‘otherness’ propagated by ‘exotic’ exhibitions? Examination of black employment prospects would certainly suggest this came to fruition. Take note, for instance, of an advertisement posted by the Volunteer Inn in Salford on 2nd May 1891 (The Era) for ‘a coloured lady or Zulu man’ to provide ‘novelty and attraction’. Or, indeed, the following advertisement which appeared in The Era on19th October 1889:

WANTED a Steady Man as Animal Keeper. One that will enter the Lion’s Den and give a performance if required. A Coloured Man Preferred.

Whilst these advertisements (which became commonplace) point to a need to fulfil specific job requirements, they also indicate something more sinister: that life for black men and women was increasingly subject to prejudice.

A Call to Action:

Whilst knowledge of black history is more widespread than it was in the 1980s, such gains are still subject, in large part, to the whim of education secretaries, museum curators and gatekeepers of modern media. Unquestionably, British history, or rather the teaching of it, is ostensibly white. So, too, is teaching on racism. Couched in etymology of racial insults, or a cursory focus on black representation in Parliament and on executive boards, understanding the history of racism is invariably marginalised. Consequently, we fail to address the root cause of division and prejudice in our society. In looking back and finding the hidden black voice and presence in British history, however, we are better able to shine the spotlight on those individuals and institutions responsible for cultivating a system in which racism took root. The Black Lives Matter protests, emerging as they did at a time of national contemplation enforced by lockdown, have shifted the gaze towards an issue long neglected by so many: black lives do matter. Let us not lose this opportunity to prioritise how we teach and talk about race, therefore. We must all be bold and step beyond the confines through which we are encouraged to understand racism today. We must use our own experiences, in conjunction with history, to advocate for lasting change. Only by understanding the roots of racism can we meaningfully strive for racial equality.