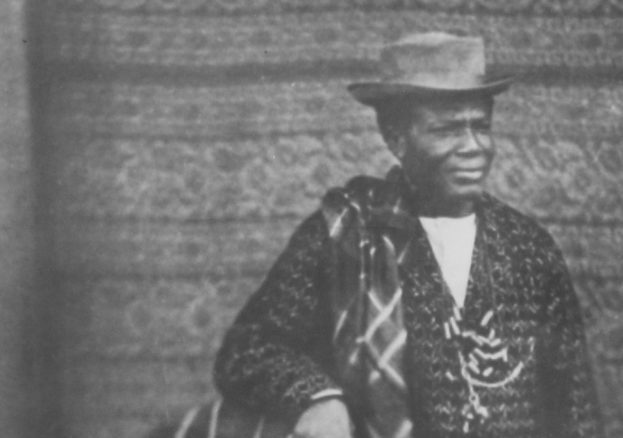

He arrived in the Kingdom of Bonny in 1833, the year the Slavery Abolition Act was passed by the British Parliament, as a child with no weight in substance, and in the space of thirty-seven years; he rose through the ranks by sheer force of personality to become a clan sub-chief, Head chief of a trading House (Opubo Annie Pepple House), and King of Opobo.

Jaja founded the Kingdom of Opobo after he retreated with members of his clan into Andony territory after Bonny civil war in 1869. King Jaja was a middleman broker of palm oil (the “Legitimate trade” that replaced the slave trade in the region) and he controlled the important trade routes from 1870 until the mid-1880s. Jaja’s troubles with British traders began in the early 1880s when George Watts, opened his factory in Kwa Ibo (an enclave within Jaja jurisdiction, which was situated along the route leading to the palm oil fairs in the hinterland). As a result, King Jaja led the first punitive expedition to the region on 11 April 1881 and that was followed by a second expedition, on the night of 16 May 1881. Following both expeditions, the disagreements between Jaja and the British Consular Authority worsened.

Another contentious issue arose when Consul Hewett met with King Jaja to discuss the Protectorate Treaty. The consul met fierce opposition from Jaja -and his chiefs- over a clause that called for free trade and freedom of movement for the British traders. (The Protectorate treaty was the forerunner of the Berlin Conference and it was designed to guarantee British traders access to the hinterland). However, King Jaja signed the treaty after the disputed clause was removed, and Consul Hewett had given him assurance in writing to state that ‘Queen Victoria did not want to take his country or markets’. On 5 June 1885, King Jaja ordered his armed men -in a show of force- to place booms across Opobo River to block the route leading to the interior when the British traders attempted to enforce the treaty.

In 1885, European traders requested a reduction in the price of palm oil due to the drop in the world price. But King Jaja rejected their request. However, when Alex and George Miller (owners of Miller Brothers & Co.) withdrew membership from the African Association -an amalgamation of British trading firms- and agreed to purchase Jaja’s palm oil at the preferred rate; they secured much of the trade within King Jaja’s jurisdiction.

The disagreement over ‘comey’ (brokerage charge), which derives from the word commission, was another cause of resentment. Consul Hewett and members of the African Association called the charge a ‘shakehand’. The word that was contrived to make it seem as though the British traders were being extorted. But they made no complaints about the comey charges imposed on them in other neighboring city-states.

What the British traders sought was free trade. The firms were quite keen to set up shop (their factories) closer to the fairs so that they could buy the palm oil directly from growers (thus bypassing the agents working for King Jaja and his chiefs).

On 19 September 1887, King Jaja was deposed for obstructing British commercial and political expansion, and he was taken out of Opobo River on 21 September 1887 for trial in Accra, Gold Coast (Ghana).

His trial took place on 29 November 1887; he was accused of administering illegal oaths to the native people in his markets ostensibly to frighten them from dealing directly with European Agents. He was accused of barring trade to the inland districts beyond his jurisdiction, of blocking the highway and sea-lane entrance into Opobo River -thereby flouting the terms and spirit of the Berlin Treaty of 1884.

On 1 December 1887, Sir Walter Hunt-Grubbe found Jaja guilty, and he was exiled to the West Indies. When King Jaja was pardoned and released to return to Opobo he died in Santa Cruz, Tenerife in the early hours of the morning of 8 July 1891.

The authors have shed more light on how big business influenced British government policy in the Niger Delta in the mid-1880s -a period agreed upon to have been the beginning of the “Scramble for Africa”. This is a well-deserved look at his rise to power and reign from a new perspective. The authors have gone further to reveal more about his private life, his closest political aides, personal attendants and family. Also, they have succeeded in merging some of Jaja’s experiences in the West Indies and Santa Cruz, Tenerife in the book.

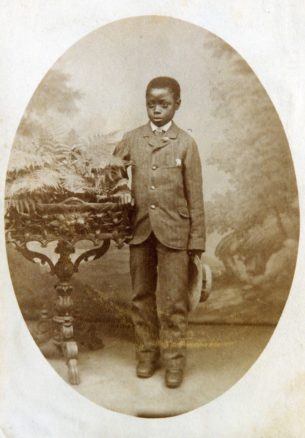

The most surprising revelation for the authors while researching the book was the discovery of Prince Waribo -King Jaja’s long forgotten son. Prince Waribo was sent to attend school in Britain, and had died after a game of cricket in the Cheshire village of Frodsham, England in 1882. The prince bore a remarkable resemblance to his father, and according to a newspaper report; he was an apt student who gave evidence of rare talent (the prince had been entrusted in the care of Mr. Walter Johnstone partner of Couper, Johnstone and Co. of Glasgow –partner of a British firm based in Opobo).

About the author

So Jaja is an author who lives in London. Educated in Worcestershire, England, studied in Indiana, USA, and City University London. He works in publishing. Aspects of British Gunboat Diplomacy is the only book he co-authored with his late father Amaopusenibo E. A. Jaja, who was a journalist and former Managing Director of the Daily Times of Nigeria Plc. (he served on King Jaja Executive Authority Opobo Town as Chairman of Queen Osunju Jaja House).