Despite the rhetoric, fatherhood in the black community (for me) isn’t shrouded in absenteeism. The majority of the men around me are active practitioners of conscientious guardianship. We actively seek advice from each other on subjects that are present and those that may transpire in the future. Group chats filled with conversations about generational wealth building, sustainable net worth growth, Trust Funds and the school curriculum lay side-by-side with invitations for family days in the park and sleepovers. I’m among a healthy number of ‘girl-dads’, so conversations about how to raise boys is at the forefront of discussion.

I’d hate for my words to come across as ‘naïve. I know there are children with absent fathers and understand the challenges this creates. However, the media, in its attempt to maximise engagement, has successfully sensationalized and spun a narrative that the absentee father is unique to the black community.

Not true.

There are many factors that distort the presence of black fathers. Black men die young. There are systemic contributors that make Black men’s early deaths even more tragic. “Many historical, social, economic, physical, and biological risk factors shape the life course of Black men and contribute to their increased rates of premature morbidity and mortality,” according to national health research in the US.

Also, an unmarried man does not necessarily mean that he doesn’t co-parent. Non-resident fathers does not mean that they don’t take an active role in raising their children. Present, active fathers in the black community are not the exception. We aren’t an outlier that should be celebrated simply for showing up (we don’t celebrate active black mothers in the same way). We represent a norm.

Western media has typecast Black men as absentee and then doubled down by creating social conditions that attempt to remove Black men from their families, limit their earning potential and block their participation in achieving a higher socio economic status. Think about the sheer numbers of Black men who are overrepresented in the criminal justice system due to disproportionate scrutiny by police officers and sentencing.

What fatherhood means to me.

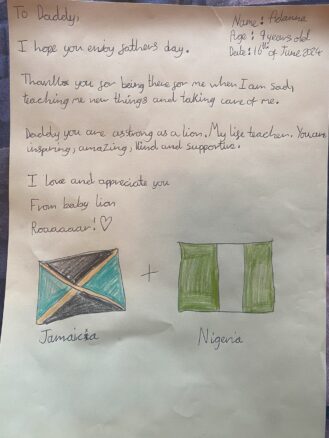

Fatherhood consists of moments that ask many questions encouraging both growth and perspective. It’s an honour to be a father. I remember when my daughter asked me what I wanted for Fathers’ Day. I told her I didn’t want anything. This didn’t stop my daughter from making me a card which stated:

My own father didn’t expect special things on Fathers’ Day and always said “you should celebrate at the appropriate time. If we are all doing our part, we should feel appreciated.”

I felt appreciated. My loved ones knew they were loved.

I am proud to be a father but first I am a man; a black man. Hope is driving me to reclaim the narrative about black fathers. Even when we have to have the ‘talk’ with our young ones or support them when they encounter racism for the first time. Even when we as black men are trying to debunk stereotypes and buck trends. It’s painful. It’s inevitable. It hurts.

Fortunately, I can draw on my brotherhood. Through each of my personal or parental

challenges I’ve had the privilege of council, whether via my own father, uncles, cousins or brothers – inherent or elected – there has been the respect, love and consideration of conscientious black men to rely on.

Manassie Wambu is a Pan-Africanist girl-dad Software Engineering Manager who appreciates travel, loves nature and is overwhelmed with gratitude.