This external narrative has perpetuated stereotypes and misconceptions, overshadowing the true story of a continent teeming with diversity, innovation, and resilience.

Yet today, a vibrant and growing movement is reclaiming and retelling the narrative of Africa’s past—a narrative that recognises its deep contributions to humanity and celebrates the enduring spirit of its peoples. African historians, scholars, and cultural leaders, including figures like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Achille Mbembe, Toyin Falola, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, are leading this crucial effort, reshaping our understanding of Africa’s history and its rightful place in the world.

The Cradle of Humanity

Africa is universally acknowledged as the cradle of humanity, the place where our earliest ancestors first emerged. The significance of Africa in the human story cannot be overstated. In the vast landscapes of Kenya, stone tools dating back 3.3 million years have been discovered in Lomekwi—tools that represent the earliest known technology. Meanwhile, in Ethiopia, the emergence of the Homo genus around 2.8 million years ago places Africa at the very heart of human evolution. These milestones, often overshadowed in mainstream narratives, affirm Africa’s central role in the history of human innovation and adaptation. They remind us that the continent’s story is not just Africa’s story, but the story of all humanity.

Ancient Civilisations and Knowledge

When we think of the ancient world, the pyramids of Egypt often dominate the imagination. These monumental structures are a testament to the engineering genius of the ancient Egyptians, a civilisation that was undeniably African. Yet, Egypt is just one chapter in Africa’s vast historical narrative. Beyond the banks of the Nile, the continent boasts other significant civilisations that have left indelible marks on history.

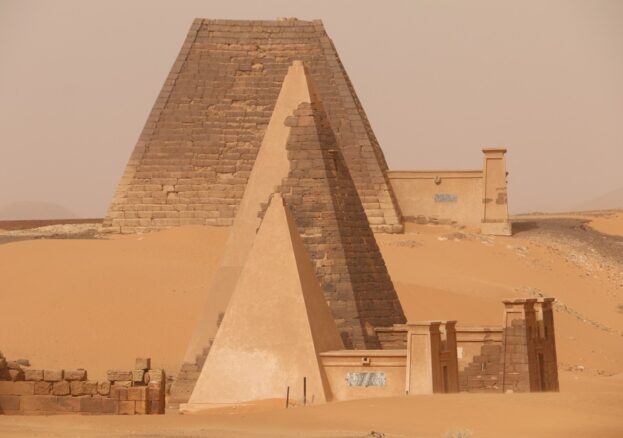

Consider the Kingdom of Kush, located in what is now Sudan. This powerful empire, with its own pyramids rising in Nubia, was not merely an echo of Egypt but a civilisation in its own right. The Kushites were masters of architecture, governance, and culture, establishing a legacy that would influence generations.

Consider the Kingdom of Kush, located in what is now Sudan. This powerful empire, with its own pyramids rising in Nubia, was not merely an echo of Egypt but a civilisation in its own right. The Kushites were masters of architecture, governance, and culture, establishing a legacy that would influence generations.

Further east, the Aksumite Empire in Ethiopia emerged as a major trading power, its monumental obelisks standing as silent witnesses to a civilisation that played a critical role in the spread of Christianity across Africa and into the Arabian Peninsula. The influence of Aksum extended far beyond its borders, contributing to the religious and cultural fabric of both Africa and the Middle East.

And then there was the Kingdom of Mali, under the legendary rule of Mansa Musa. Known as one of the wealthiest men in history, Mansa Musa’s reign from 1312 to 1337 transformed Mali into a global centre of wealth, culture, and scholarship. His famous pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324, where he distributed so much gold that it caused inflation in the regions he passed through, is a story often told. But what is less frequently highlighted is Mali’s significance as a beacon of learning. The city of Timbuktu, with its vast libraries and centres of Islamic scholarship, became synonymous with knowledge. Manuscripts from Timbuktu, covering subjects from astronomy to law, are not just relics—they are living testimonies to a time when Africa was at the forefront of global intellectual life.

The civilisation of Great Zimbabwe, flourishing between the 11th and 15th centuries, stands as a powerful testament to Africa’s architectural ingenuity. The massive stone walls of the Great Enclosure, constructed without mortar, are an enduring symbol of the kingdom’s sophistication and its role as a major trading hub. Strategically located near gold mines and along vital trade routes, Great Zimbabwe connected the interior of Africa with the wider world, exporting gold and ivory in exchange for luxury goods from as far afield as China and Persia. The conical towers and the iconic Zimbabwe Bird carvings reflect a society rich in religious and political complexity, with a legacy that stretches far beyond its borders.

The Benin Kingdom, located in what is now southern Nigeria, is another example of Africa’s advanced artistic and technological traditions. Reaching its height between the 13th and 19th centuries, Benin is particularly renowned for its intricate Benin Bronzes—masterpieces of metalworking that have captivated the world. Created using the lost-wax casting technique, these bronzes are not merely beautiful; they are powerful expressions of the kingdom’s history, mythology, and royal power. The Benin Kingdom was a highly organised and centralised state, with a sophisticated system of governance and a military capable of defending its interests. Its capital, Benin City, was described by European visitors as one of the most impressive cities they had ever seen, with wide streets, grand palaces, and an extensive system of walls and moats.

These civilisations, and others like them, challenge the outdated narratives that have too often portrayed Africa as a passive recipient of external influences. Instead, they reveal a continent that was deeply interconnected with the broader world—a place where knowledge, culture, and innovation flourished.

Africa as a Beacon of Learning and Scholarship

Africa’s legacy as a centre of learning is further exemplified by its renowned institutions of higher education, such as the University of al-Qarawiyyin in Morocco and Al-Azhar University in Egypt. These universities, among the world’s oldest, were vibrant centres of knowledge that attracted scholars from across the globe.

The University of al-Qarawiyyin, established in 859 AD in Fes, Morocco, by Fatima al-Fihri, stands as a symbol of the continent’s intellectual heritage. Fatima al-Fihri, a visionary woman, used her inheritance to create a mosque and university that would become a leading spiritual and educational hub in the Muslim world. Al-Qarawiyyin played a crucial role in the development of Islamic jurisprudence, mathematics, astronomy, and medicine, influencing intellectual developments far beyond North Africa.

Similarly, Al-Azhar University in Cairo, founded in 970 AD, remains one of the most prestigious institutions of Islamic learning. It has been a beacon of scholarship, particularly in the fields of theology, law, and philosophy. Scholars from all over the Islamic world came to study at Al-Azhar, which became a key site for the exchange of ideas and the preservation of knowledge during the Middle Ages.

These institutions challenge the narrative that positions Africa solely as a recipient rather than a producer of knowledge. They highlight the continent’s significant role in global intellectual and cultural exchanges, showing that Africa was not isolated but deeply interconnected with the broader world. The contributions of African scholars and institutions to global knowledge and culture are a testament to the continent’s enduring legacy as a centre of learning and innovation.

The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A Dark Chapter

The Transatlantic Slave Trade marks one of the darkest chapters in African history. Millions of Africans were forcibly taken from their homelands, subjected to brutal conditions, and sold into slavery. This inhumane trade inflicted deep psychological, social, and economic wounds on African societies, tearing apart communities and devastating cultural continuity. Yet, the resilience of those who survived and the rich cultural traditions they maintained and transformed in the diaspora are testaments to their enduring spirit and strength.

Colonialism and the Struggle for Independence

The partitioning of Africa during the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 imposed arbitrary borders and initiated a period of intense exploitation and cultural suppression by colonial powers. Colonialism sought to erase and replace African identities, instilling foreign governance and ideologies. However, the 20th century witnessed a powerful wave of decolonisation as African nations, inspired b

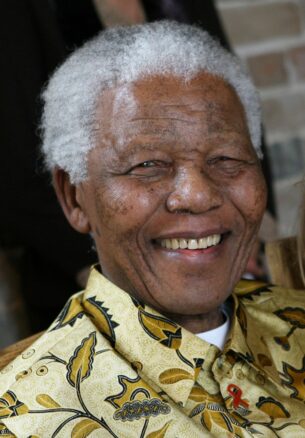

y visionary leaders like Kwame Nkrumah and Nelson Mandela, fought for and achieved independence. These leaders championed not only political freedom but also the reclamation of African identity, culture, and history.

Reclaiming and Celebrating African History

Today, the movement to reclaim Africa’s history is thriving, led by a new generation of African historians, scholars, and cultural leaders. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, a Kenyan writer and academic, has been instrumental in advocating for the decolonisation of African literature and history, emphasising the importance of African languages in preserving and promoting indigenous narratives. Achille Mbembe, a Cameroonian historian and political philosopher, offers critical analyses of postcolonial Africa and globalisation, providing new perspectives on issues of sovereignty and identity. Toyin Falola, a Nigerian historian, has extensively contributed to the understanding of African history, culture, and politics, while Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, through her acclaimed novels, explores complex themes of history and identity, notably in Half of a Yellow Sun.

Other influential figures include Wole Soyinka, a Nigerian playwright, poet, and essayist, whose work has been instrumental in celebrating African culture and critiquing colonial and postcolonial power structures. As the first African laureate to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, Soyinka’s plays, such as Death and the King’s Horseman, illuminate the depth and complexity of African traditions, while his essays and poetry continue to inspire generations. His contributions to literature and thought showcase the resilience and intellectual richness of African societies, reinforcing the importance of reclaiming and honoring African narratives.

Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gatsheni, a Zimbabwean scholar, is a leading voice in decolonial theory, critically examining the lasting effects of colonialism in contemporary African societies. The late Ali A. Mazrui, a Kenyan-born academic, profoundly influenced the understanding of African cultural and political dynamics through works like The Africans: A Triple Heritage, which explores the complex interplay of indigenous, Islamic, and Western influences in shaping African identities.

Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela, a South African psychologist, has provided crucial insights into the processes of healing and reconciliation post-apartheid, through her research on trauma and memory. Her work, including A Human Being Died That Night, delves into the possibilities of forgiveness and the psychological and social dimensions of dealing with historical injustices.

These scholars and writers are vital in the ongoing effort to reclaim and retell the narrative of Africa’s history. They challenge long-standing stereotypes and misconceptions, illuminating the continent’s rich heritage and significant contributions to global culture. This movement is not merely about correcting historical records but also about asserting a vibrant and diverse African identity that is integral to the global narrative.

Reclaiming the narrative of African history is not just an academic exercise; it is a crucial endeavour that challenges outdated stereotypes and celebrates the continent’s rich heritage. By presenting a fuller, more accurate story, we honour Africa’s past and inspire future generations. Africa’s history is a testament to the strength, creativity, and resilience of its people—a narrative that deserves to be told and celebrated in all its complexity and glory. As we continue this journey, it is essential to support and engage with African voices, ensuring they are central in shaping the global discourse about Africa’s past, present, and future.