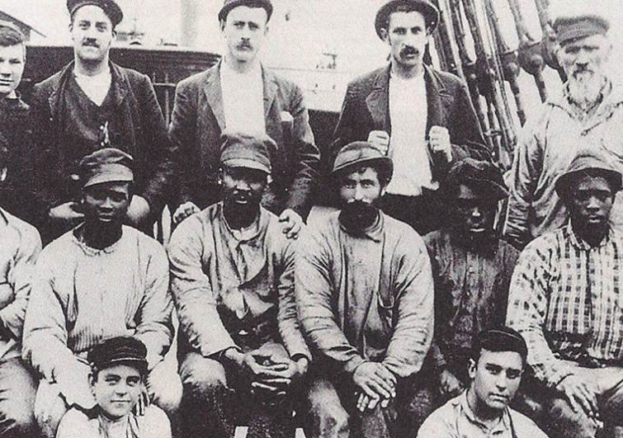

Although little is known about Blake himself, he would be one of thousands of black seamen from all over Britain and the Commonwealth who would serve in the Mercantile Marine.

The role of the Mercantile Marine itself was many and varied, from carrying troop and armaments to British and Commonwealth armed forces all over the globe, to ensuring Britain had the food raw materials necessary to continue fighting the war, for example nearly two-thirds of the food and drink consumed by the British population came from abroad, 100% of its sugar, 79% of its grain, 65% of its butter and 40% of its meat.

In 1914, an estimated third of British merchant fleet crews had been born abroad. Mercantile Marine Medal records show, for example, that 255 recipients gave their place of birth as the West Indies, 511 as Jamaica, 133 as Trinidad. The numbers of men joining from the Caribbean would run into thousands, and they would be joined by large numbers of West Africans, including men from Gambia, Ghana (then called the Gold Coast) and Sierra Leone.

At the same time many British born black seamen joined up from British ports such as London, Glasgow, Cardiff, Hull, Liverpool, Southampton, and Barry in Wales.

Many black and Muslim Asian seamen worked in the engine rooms of ships, undertaking dangerous and exhausting jobs, such as stokers, bunkermen, coal boys, and trimmers. Most black seamen were given smaller berths, less pay and fewer rations and suffered high rates of illness and injury due to their poor conditions.

By the end of the First World War, more than 3,000 British flagged merchant and fishing vessels had been sunk and nearly 15,000 merchant seamen of every nationality and background, had died, with many having no grave but the sea.

After the war some black seamen jumped ship, got work, married, and settled in the British ports where they had served. They were to suffer severe discrimination and racism as demobilised servicemen returned and felt resentful at what they saw as their jobs being taken by black workers.

As the nation’s largest Armed Forces charity, the Royal British Legion (RBL) is dedicated to ensuring that all those who served and sacrificed, and who continue to do so, in defence of our freedoms and way of life, from both Britain and the Commonwealth, are remembered.

In our acts of Remembrance, the RBL remembers,

- The sacrifice of the Armed Forces community from Britain and the Commonwealth.

- Pays tribute to the special contribution of families and of the emergency services.

- Acknowledges the innocent civilians who have lost their lives in conflict and acts of terrorism.

The story of Black British and Black African and Caribbean service and sacrifice is one that we are keen to share, a story of men and women who have done so much in defence of Britain and in protecting all our citizens. A story that is replete with stories of bravery and courage, as epitomised by Victoria Cross winner Johnson Beharry.

Therefore, to mark 100 years since Britain’s current Remembrance traditions first came together, the RBL has bought together over 100 stories of British and Commonwealth African and Caribbean service and sacrifice. The stories range from the First World War to the present day and are of servicemen and women from across Britain, Africa and the Caribbean, representing both the armed forces and emergency services.

Therefore, to mark 100 years since Britain’s current Remembrance traditions first came together, the RBL has bought together over 100 stories of British and Commonwealth African and Caribbean service and sacrifice. The stories range from the First World War to the present day and are of servicemen and women from across Britain, Africa and the Caribbean, representing both the armed forces and emergency services.

The RBL wishes to offer special thanks to Stephen Bourne for his help in putting these stories together. Stephen Bourne has been writing Black British history books for thirty years. For Aunt Esther’s Story (1991) he received the Raymond Williams Prize for Community Publishing. His best-known books are Black Poppies (2019) and Under Fire (2020). His latest book Deep Are the Roots – Trailblazers Who Changed Black British Theatre was recently published by The History Press. For further information about Stephen and his books, go to his website www.stephenbourne.co.uk