To accompany Rosa-Johan Uddoh’s current exhibition ‘Practice Makes Perfect’, Focal Point Gallery have commissioned a new essay by black feminist writer, researcher and organiser Lola Olufemi:

There is a problem with History. The problem begins with the idea that History is the story of humanity featuring major and minor characters. To be included in the story is to know and see yourself in the past, to find yourself in the textbook and name with ease, the social and political triggers for the events that constitute you in the present. We are made up of this stuff of the past, it is how we say to others, look, we were there, we exist. But when Black people are banished to an invisible realm by the construction of narratives of humanity in which they do not feature, the function of History as a means of seeing and being seen is thrown into disarray. What does History mean when Black people’s lives in Britain are deemed not worthy of scholarship by leading institutions or not even present before 1948; or when the material conditions of racialised existence are reduced to questions of iconography, of statues going up and coming down?

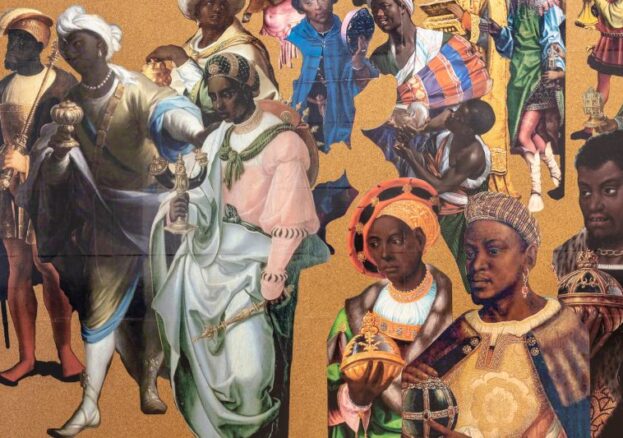

Rosa Johan Uddoh is trying to figure out the connection between the meticulous “erasure” of Black History and the reflections of blackness we see in popular media. Lately she is preoccupied with how racialisation marks one’s most formative years. How does racism change the child or shape the life of the teenager? The space for her reflection erupts from moments of tension, most recently the public execution of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer on 25th May 2020. This tension is met with a scattering of bodies on the street in protest, demands from the grassroots for the abolition of the systems of power that kill, suppress, restrict and surveil black life but also navel-gazing statements of impotence from institutions about their complicity in racism. This cyclical tension clears a space to explore the constitutive force of racism in everyday life, how it contours everything at the level of the quotidian; school, friendships, work, curricula, art-making. Uddoh’s work sits here, in the swirl of conversations about racism that have come to define the popular culture arena in the last year. For her, popular culture is a site of play, where counter-revolutionary narratives about blackness unfold for consumption, where a limited desire to be seen by others and by History with a capital H marks everything. Uddoh follows Stuart Hall, who writes “Popular culture, commodified and stereotyped as it often is, is not at all, as we sometimes think of it, the arena where we find who we really are, the truth of our experience. It is an arena that is profoundly mythic. It is a theater of popular desires, a theater of popular fantasies.” Her latest show, Practice Makes Perfect, lets popular fantasy run wild.

The virus has meant that for the first time Uddoh is stepping back from public performance. Instead, she is testing out theories of relation and play by putting others on the stage. In ‘Practice Makes Perfect’, a video workshopped with a group of young people in collaboration with filmmaker Louis Brown, together the group destroy and remake her written piece WINDRUSH: A TONGUE TWISTER into a series of performances and game show tasks. Here History turns into something light and malleable, the children force themselves into the various stories of black migration and protest through Uddoh’s writing and their speech, mushing History like playdoh in their hands. The video poses a series of questions: what is the interplay between text and speech? What happens to a text when you read it out loud, what strange power does it have to provoke or galvanise? These are questions that can only be answered in collaboration; a dimension of Uddoh’s work that is startlingly clear. Her interest in performance enables her to expose the mundanity of the shows we put on for each other; shows of race, of gender, of sexuality. She knows we have all been given a role and is working, using a deconstructive method, to pull back the curtain and expose the writer. In doing so, she prompts us, the audience, to loosen our adherence to the parts we’ve been assigned.