Today, most young people and adults with short memories, are likely to find it hard to believe that Britain was once the most important market for reggae music, outside of Jamaica.

In what can be argued as reggae’s golden age – the 1960s and 1970s, Island, Trojan and Pama (later becoming Jet Star) were the key reggae record companies that exposed reggae to the global market. They were initially based in Brent, which is part of the reason the north-west London borough, generally, and Harlesden, more specifically, can claim to be the capital of reggae in Britain.

It was Britain as the main Jamaican migration destination from the late 1940s onwards, and companies such as Jet Star, which at one time stood as the world’s biggest reggae company, that helped sell reggae globally, be it records or live performances.

That point was articulated by reggae journalist and music publisher Kennedy ‘Prezedent’ Mensah  and others in a vox pops documentary I begun filming in 2012, initially to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the ‘independence’ of Jamaica. ‘Britain’s Contribution To The Development Of Reggae’ kicks off with Mensah saying: “It was Britain that was the first port of call for reggae as an export. It was Britain that was the first market…”

and others in a vox pops documentary I begun filming in 2012, initially to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the ‘independence’ of Jamaica. ‘Britain’s Contribution To The Development Of Reggae’ kicks off with Mensah saying: “It was Britain that was the first port of call for reggae as an export. It was Britain that was the first market…”

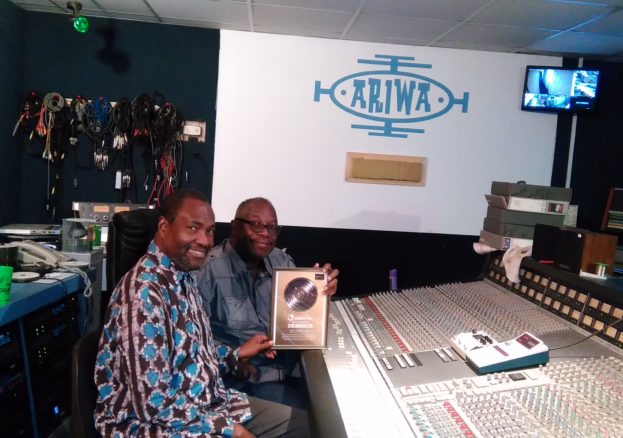

Whilst record producer and record company owner Neil ‘Mad Professor’ Fraser adds:“England was the market that brought in the real money. You had artists such as Millie Small, Desmond Dekker ‘You Can Get It If You Really Want’, Bob & Marcia ‘Young, Gifted & Black’. And coming down into the 1970s, John Holt ‘Help Me Make It Through The Night’, and of course Bob Marley and people like Dennis Brown ‘Money In My Pocket’, generating earnings, generating foreign currency that was sent back home to Jamaica.”

But as I regrettably had to point out in my recent VP Records @ 40 article in The Weekly Gleaner, New York, US-based VP now has the mantle of being the biggest reggae company in the world.

As part of its year-long celebrations of its 40th anniversary, the company’s key US-based executives came to London to join in the celebratory activities highlighting the company’s achievements through an art exhibition, talks, and club night.

However, this is becoming the exception, rather than the norm. In days gone by every Jamaican reggae producer or artist looked to coming to Britain to either tie up a licensing deal or to perform. We created the global market for reggae music. But today, these producers and artists look mainly to the US or Europe.

A case in point being Buju Banton’s ‘Long Road To Freedom’ tour, which touched down this summer in several European destinations, but not in Britain.

The fact’s that Britain for many years has hardly had any huge reggae festivals which attract the hottest or big name brand acts. The action’s in European countries such as Spain, Germany and France. Even small, eastern European countries such as Croatia and Slovakia, have been attracting major reggae acts in recent times.

Coming back to Britain, in spite of general resistance by radio, which was the main influencer in the 1970s-80s, reggae was able to crossover into the pop charts. In the 1960s, Millie’s ‘Boy Lollipop’ ska hit got to no. 2 both in Britain and the US, and Desmond Dekker & The Aces’ ‘The Israelites’ delivered Jamaica’s first chart topper in Britain’s pop charts.

Even British pop and rock bands, such as The Beatles, Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin, got in on the act, creating their versions of reggae!

In the 1970s, Trojan held sway, delivering several crossover hits, including two chart-toppers, Dave & Ansel Collins’ ‘Double Barrel’ and Ken Boothe’s ‘Everything I Own’. Sadly, it was as a result of becoming financially over-stretched from chasing pop hits that the company was taken over by Saga Records in 1975. Incidentally, Janet Kay became the highest placed female British reggae singer when ‘Silly Games’ got to no. 2 in 1979.

In the 1980s, love song covers provided a couple of chart-toppers for UB40, including ‘Red Red Wine’, whilst Aswad got to the pinnacle with ‘Don’t Turn Around’.

In the 1990s, Swedish group Ace Of Base had a top 5 hit with another reggae-fied version of ‘Don’t Turn Around’, but that’s after they had led the charge at the top of the charts in May 1993 with the pop-reggae ‘All That She Wants’, with UB40 in the runner up position with ‘(I Can’t Help) Falling In Love With You’, and Inner Circle at no. 3 with ‘Sweat (A La La La La Long)’. And coming in at no. 7 was the British female singjay duo Louchie Lou And Michie One with ‘Shout (It Out)’.

The mid-1990s, it wasn’t just sweet vocalists like Bitty McLean who were troubling the top echelons of the pop charts, toasting by the likes of Pato Banton, was becoming common, particularly as dancehall exploded from the clubs unto pop radio and the charts.

Indeed, the week Shaggy scored the first of his four chart-toppers in March 1993 with ‘Oh Carolina’, something unique happened – for the first time the top 3 slots were occupied by reggae records. Snow was at no. 2 with ‘Informer’, whilst Shabba Ranks held the no. 3 spot with ‘Mr Loverman’.

It can be argued that Britain’s love affair with reggae since those days has been pretty down hill on the commercial front, in terms of pop radio support, chart hits, and major festivals.

It’s not just pop radio that’s not interested, so too are the major labels. And even in the case of Island Records UK, which has a long history with reggae, it doesn’t look like they’re that bothered by their rich reggae heritage.

From last year when we were planning for this year’s IRD (International Reggae Day), particularly as it’s Island’s 60th anniversary, we tried on several fronts to engage them in the event and to show their support for reggae by advertising in the IRD @ 25 supplement that run in The Weekly Gleaner. But there was no interest. It’s like the present management has no idea that the company was literally built on reggae!

Somehow, I think it would have been a different story if co-founder Chris Blackwell or the last president Darcus Beese, were in charge. Contrast that with the management that now own Trojan. Not only did they come on board to support IRD this year, but they are continually engaging with the reggae community, be it through the eponymous sound system, regular releases and offering of competition prizes.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Reggae Fraternity UK (RFUK) is an umbrella organisation that aims to improve the professionalism and networking opportunities within the reggae sector. Catch A Fire (CAF) is a regular first Sunday of the month club night which takes place Upstairs at The Ritzy in Brixton, south London.

CAF nights have the distinction of always featuring live acts. However for this December 1 session, it has joined forces with RFUK to precede the entertainment with a free conference that draws on station owners, producers, radio pluggers, record labels, DJs, broadcasters and reggae fans to explore how radio can best serve reggae in this country.

And my organisation, BritishBlackMusic.com/Black Music Congress (BBM/BMC) is convening a reggae stakeholders meeting on December 10 at Harlesden library, where it will explore working with potential partners to deliver reggae focused events as part of the Brent, London Borough Of Culture (BLBOC), IRD and British Black Music Month 2020 programming. Details can be found at http://bit.ly/RSHM8.

Kwaku is a historical musicologist, founder of BritishBlackMusic.com/Black Music Congress and UK co-ordinator of International Reggae Day