In many regions of the world, ‘anthropology’ is a dirty word. Accused of being the handmaiden of colonialism and tainted by its associations with scientific racism and cultural evolutionism, the discipline has had to confront a difficult history.

As a filmmaker-turned-anthropologist, with a strong interest in history and awareness of my own family’s entanglement in British imperialism (my grandfather was forced to seek refuge in Japan having been a militant anti-colonialist in India in the early 1940s), I have a particular interest in the visual archives of colonial anthropology.

I started working in West Africa soon after completing my PhD in 2001. Bringing my earlier career in film and television production together with my anthropological training, I developed a project to assemble an audio-visual record of Sierra Leone’s recent civil war alongside one of my professors. While that project did not materialize, it served to introduce me to Sierra Leone, where I have continued to work ever since.

Through my research in Sierra Leone, I became familiar with the figure of Northcote Whitridge Thomas (1868-1936). Thomas was the first anthropologist to work in Sierra Leone. He was also the first ‘Government Anthropologist’ to be appointed by the British Colonial Office. In this capacity he conducted a series of anthropological surveys in West Africa, completing three year-long tours in Southern Nigeria between 1909 and 1913, before being sent to Sierra Leone in 1914-15.

Although his published reports are not especially inspiring, when I began exploring Thomas’s career in depth, I discovered that a remarkable array of material had survived from his surveys dispersed in various institutions, including thousands of photographs, hundreds of wax cylinder sound recordings, large collections of artefacts and botanical specimens, and lots of unpublished fieldnotes and manuscripts. Little of this archive had been properly examined in the 100 years since it had been assembled. What became apparent as I explored the material was that, despite his position as Government Anthropologist, Thomas was not a compliant functionary of the colonial administration but was a controversial figure and often critical of the administration that employed him. Indeed, his resistance to the colonial authorities made him unpopular and cut short his career.

My interest having been piqued, I developed a three-year research project to further investigate both the historical context of Thomas’s work in Nigeria and Sierra Leone, and – more importantly – to examine the value of these anthropological archives to different communities in West Africa and the UK today. Can they only be regarded as legacies of an insupportable colonial project? Or are there other ways of engaging with them beyond a colonial critique?

The project, ‘[Re:]Entanglements / Museum Affordances’ is funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council. You can learn more about the project’s many activities and discoveries at the website https://re-entanglements.net. Here, I focus on some of our work with Thomas’s photographs, including a short film we have made entitled Faces Voices, which has been shortlisted for a prize at RIFA 2019, the annual Research in Film Awards. RIFA is organized by the Arts & Humanities Research Council, and is the only awards entirely dedicated to bringing to life arts and humanities research through film.

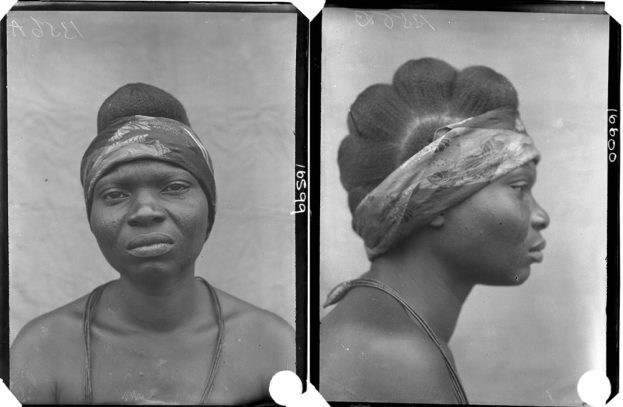

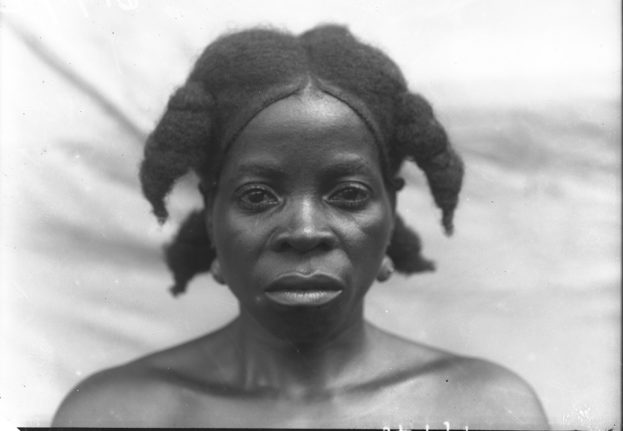

In his six years in West Africa, Thomas took approximately 7,500 photographs. These photographs include images of markets, farming, architecture, arts, rituals, dance and many other aspects of everyday life – a remarkable record of the region’s cultural heritage. About half of the photographs, however, are of a particular anthropological genre known as ‘physical type’ portraits. The head and shoulders of a subject are photographed from the front and then the side, usually in front of a plain canvas backdrop. Such photographs have come to epitomise the violences of colonial science, reducing individuals to nameless specimens to be collected, ordered and categorized into racial or tribal types.

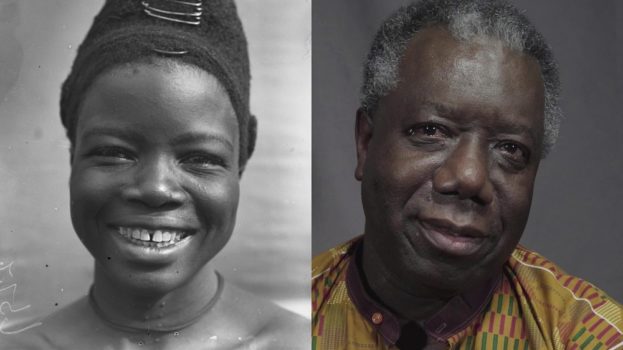

Looking through Thomas’s photographs, then, is to gaze upon a myriad faces – faces of women, children and men. Some have elaborate hair styles, others complex scarification marks. Some gaze directly at the camera, while others avert their eyes. Some are smiling, some appear defiant, but the expressions of the majority are inscrutable. All, of course, are silent, and we can only guess what the experience of being photographed by a Government Anthropologist felt like for them. What did they make of this pith-helmeted white man, with his entourage of carriers and boxes full of strange equipment? Was the encounter a violent one? Was it humiliating? Was it a welcome distraction from everyday chores? An amusing diversion? Some are dressed in their chiefly regalia. Did they feel empowered as they sat for the anthropologist? Or did they feel exploited or compelled by force?

In the Faces Voices film, we invited participants to reflect on some of the faces captured in Thomas’s physical type photographs and to comment more generally on their significance. We find that the same portrait may invite quite different interpretations. Where one sees coercion, another detects boredom. The crushing experience of colonialism may be found in one subject’s expression; optimism, defiance or resilience is discerned in another. Perhaps most surprising is the sympathetic view – even identification with – the face of Northcote Thomas himself.

Juxtaposing the faces of Thomas’s anthropological subjects, with the eloquent, questioning voices of contemporary commentators, the film complicates any simple reading of the colonial archive. While we should never forget the circumstances in which they were taken, these photographs elicit a plurality of responses, in some cases reinforcing senses of the violence of colonial subjugation, yet in others confounding such expectations, opening up more ambiguous, even more hopeful readings. Laughter, too, is to be found in this picture archive. As one respondent passionately observes, the smiling face of a young woman photographed over a century ago carries an important message for young people today: ‘There is a certain powerful conviction in that smile that we shall overcome, we shall overstand, we shall overcome’.

The RIFA 2019 prize-winners will be announced on 12 November at the BFI Southbank. Faces Voices was directed by Paul Basu (SOAS University of London) and Christopher Allen (The Light Surgeons) as part of the [Re:]Entanglements / Museum Affordances project, funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council. The project is being led by Paul Basu, Professor of Anthropology at SOAS University of London. Project partners include the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology, the British Library, the Royal Anthropological Institute and the National Archives. The project will culminate with a large exhibition at SOAS’s Brunei Gallery in October-December 2020.

For further information please visit https://re-entanglements.net.