The dates of John’s police career are surprising, 1835 to 1846. The story began with John’s father Thomas landing at Whitehaven in the mid 1700’s where he was ‘considered’ a slave by the Senhouse family of Calder Abbey, West Cumberland. He was released and married a pauper where they had a number of children, the last but one being John, and they grew up in the Carlisle area.

John married Mary Bell of Longtown and they had three children who were born there, William, Mary, and Jane. This Kent family also settled in the Carlisle area. He was first employed as a constable at Maryport, named after Mary Senhouse, and John gave evidence to Senhouse Magistrates. This bizarrely means that within the space of one generation, the father was ‘considered’ a slave and the son a pillar of the community, upholding the law. At Maryport John saved his colleague from a threat to his life, he also dealt with a serious and prolonged disorder where he fought against a group of men, who injured him, but he brought them before the courts.

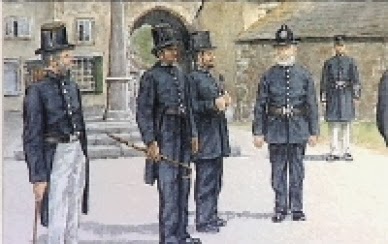

Following this he moved back to Carlisle as a supernumerary officer, then became a Watchman, later progressing to a day constable. It was at Carlisle that was the busiest period of his policing career. He initially saved a 17-year-old from drowning, who tragically then died 6 hours later. John was cautioned for his conduct towards the night constable, but would go on to work with him, also saving him from serious assault on several occasions. The police of those times were also the fire service and John regularly got more of the insurance reward money than other officers, indicating his commitment to his duty; he was known to be a powerful, muscular man. On one occasion John was threatened by three men, one with a knife, but on his own he disarmed and arrested the knife wielder, the others were later arrested. He also worked through serious election riots in the city when he and others were stoned, with one officer was killed by being struck with a sailor’s life preserver, a lead weighted Narwal tusk.

The question usually asked is whether John suffered any discrimination in his career? He was referred to locally on the streets as ‘Black Kent’, perhaps unsurprisingly for the 1840’s. This however was by a community that largely could neither read nor write and likely had never gone outside the city boundaries. Only one article refers to a quack doctor ‘ill-using’ Constable Kent, although it does not say how. On one occasion at court John was heavily criticised by the judge, believing on the evidence, that he had acted in an immoral or dishonest fashion and wanted the Watch Committee to inquire into the circumstances. They did, and reported that the judge had been misinformed, and Constable Kent had acted with the greatest propriety.

John was eventually dismissed for drunkenness in December 1844, following an earlier suspension. This was not uncommon, his replacement was sacked within a year for the same reason, and these were the days of cholera and typhoid and ‘night soil’ or human waste, being thrown into the street. Carlisle Magistrates then employed him for a short period as a bailiff. He then became a parish constable at Longtown, and is recorded dealing with two further incidents there, one an assault where a three-pronged fork was driven into a man’s chest, close to his heart. In the census of 1851, he was a railway policeman in Carlisle. In later life he was employed by the railway as an attendant, known to be a very conscientious man. As a civilian he continued to give evidence in two civil cases in support of the public, his evidence turned each prosecution in their favour.

John died at the age of 81 years of peritonitis and the local newspapers printed eulogies, one headed: ‘The Death of a Carlisle Notable’. He was buried in the city cemetery in aknown but unmarked plot.

John’s life was revealed in a new book, published in March 2018 by Raymond Greenhow, himself a former officer. The obvious question to be answered was: ‘were there any descendants of John, or his father Thomas; if so, were they aware of their African heritage?’ Following talks in local forums on John’s life and research on internet ancestry sites, five branches of descendants have now been identified, they themselves having extended families. None were aware of their African ancestor Thomas Kent, and one is a descendant of John himself; each family member has eagerly bought a copy of the book. Work still continues on the Kent family heritage, other branches are known to be in the Manchester, Durham, and South West of England areas.