This space, currently housing the exhibition: “No Colour Bar: Black British Work In Action 1960-1990” is fitting when you consider that a building destroyed in the Blitz has now been rebuilt and houses Art created by the people our government wanted to help rebuild Britain after World War Two.

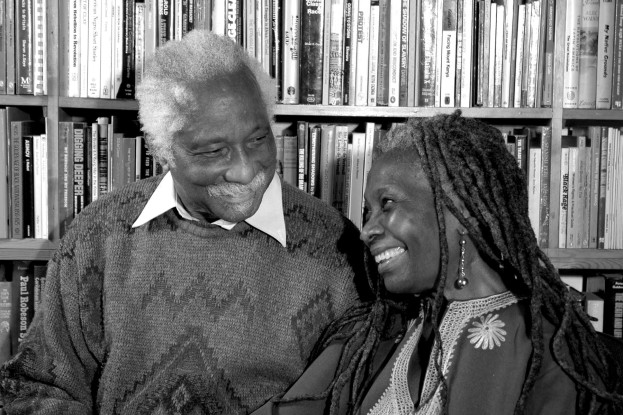

Inside, I was to meet Eric Huntley. Once an important part of the Peoples Progressive Party in what was formerly known as British Guiana (now Guyana), he and his wife, Jessica Huntley came to the UK in 1956, after Eric’s incarceration in 1955 for leaving his Guyanese village without permission.

Now in Britain, his newfound freedom would allow his once oppressed ideals of independence and equality to be heard, ultimately changing the tide of Britain’s colonial rule in the West Indies.

But before he, his wife and a group of friends changed the power dynamic of the British Caribbean, there were several years of political and social struggle.

“We were campaigning almost every week.” Eric tells me whilst nodding his head. In the space of 12 years, the Huntleys would find another effective way to have their message heard; become a publisher and sell, or at least give out books and leaflets at the rallies they attended.

By 1968, this ideal had become a reality and now the Huntley’s had something a little more substantial than a weekly picket rally- a bookshop and a publisher; Bogle L’Ouverture which took residence in the front of their family home.

“Until about 76’ or 77’ it was in the front room of our house.” Eric explains. “It wasn’t well-advertised and only people who knew it was there could come in and know it was a bookshop.” When I asked how, his response was simple. “We kept the curtains up so it looked like a house.”

Despite appearances, the Walter Rodney Bookshop was not an entirely covert operation. Students, Teachers and the general public alike began flocking to the shop for more than just purchasing books, but for the social and intellectual elements also. By the end of 1968, the Rodney’s had begun working on a paper with a Scholar who had been exiled from Jamaica, Walter Rodney.

“Never underestimate the power of the media. The media is a powerful weapon.” Eric warns me. It is a powerful warning too. The collection of Rodney’s papers in which de delivered whilst in Jamaica, found themselves in the publication of ‘The Groundings With My Brothers’.

Upon the books release in 1969, many considered the publishing a revolutionary and even at times inflammatory exposé of colonial attitudes in the Caribbean and how they should be challenged. Others found it to be a relevant and much needed spotlight being shone on the fragility of a new government, one which had been left deliberately weakened by its ex-colonial master. What this proved to be was more than a case in which someone sought to have their exile overturned. Now, it would be the building block for a presidential charge less than a decade later and Eric Huntleys Bogle L’Ouverture was involved.

The success of Rodney’s paper and the subsequent publications meant a cloud of suspicion loomed over the Huntley home. So when a nosey curtain-twitching neighbour called the council to complain that a commercial property was being operated from a residential address, Eric, Jessica and their children would be forced to do things differently.

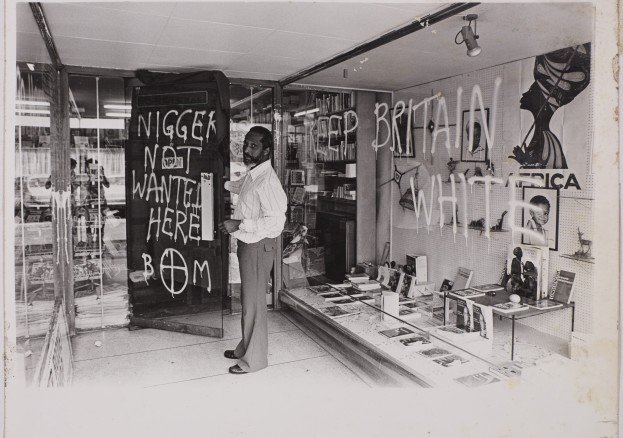

This force of hand is what prompted the re-opening of their bookshop in 1978. Now in a commercial dwelling, Eric and Jessica Huntley found more sturdy ground with their ‘revolutionary’ titles.

“I don’t like the label left wing. It has too many connotations. If someone labels you left wing it creates the image that you agree with everything the left wing does. There are progressive and reactionary people. The left can do bad things too. So don’t label me a left wing person. I can critique the left, just as much as I do the right.”

It is this sort of language which makes me understand why Eric Huntley and his publishing company; Bogle L’Ouverture were so prolific and influential. This determined and very individualistic approach to what they were doing meant that writers, poets, speakers, intellectuals and allies found a voice in Bogle L’Ouverture, setting the seed of influence which would sprout in the coming months and years.

And in the time of blossom, it had become evident that Bogle L’Ouverture was a symbol, a flagrant reminder that things were changing at a rapid pace in a conservatively minded Britain. No longer were high streets dominated by white-only businesses; the Race Relations Act of 1965 made sure of that. Now, the Walter Rodney bookshop was one of hundreds of shops owned by Black and other Ethnic minority citizens, so naturally, it was attacked by the National Front.

“They used to leave dog faeces on the front of the shop.” Eric chuckles. It is a strange response to something many of us would consider vile and revolting. “They must have thought it would scare us away. But I’m still here today.”

“I mean. It was difficult.” He continues. “The Police never got involved. If you went down to your local police station, sometimes they said it was a domestic thing, or they simply weren’t interested. So we banded together, us and the community. We would help each other. Clean a shop if it got attacked… that sort of thing.”

This community spirit kept the now renamed, Walter Rodney Bookshop; dedicated to Rodney after his assassination whilst running for Guyanese Presidency in 1980- relevant and in the interest of the people. This could not be anymore true when the Huntleys began offering legal advice to the young men and women caught up in the frequent, yet regularly unsubstantiated ‘Sus’ stop and searches and again for the days and months following the 1981 Brixton Riots.

It is easy to gloss over the very subtle and background achievements Eric Huntley has been involved in with his wife, Jessica and Bogle L’Ouverture. It is because of this very reason as to why painting Eric Huntley as a historical figure is difficult.

Perhaps this is because of the way we are expected to understand what a ‘hero’ is. We very regularly take note of the front man in the theatre, but forget that the stage is built for the cast to perform on. Eric Huntley is such a person, building the stage in the form of supporting performers and speakers by making their literature a public interest.

Of course, how far the influence of a book reaches is impossible to gauge. Aside from the success of the Author, how do you know how many people the book has actually changed? How do you know how many conversations it has spawned?

The stage on which Huntley’s work supports is influential whilst being almost untraceable. Follow the trail of Linton Kwesi Johnson’s career and you will find that it begins by being signed to Bogle L’Ouverture. If you follow the conversations of Walter Rodney’s ‘How Europe Underdeveloped Africa’, you will find Bogle L’Ouverture is its first publisher. When you look at partnerships for Notting Hill Carnival, Eric and Jessica Huntley are within the magical six degrees of separation from the event organisers and liaison officers. Just take a look at some of the speakers at almost any anti-colonial rally between 1972 and 1990 and you will find yourself at least one reference, to at least one speaker, writer or affiliate with Bogle L’Ouverture.

So perhaps it is difficult to fathom that in 1989, the Walter Rodney Bookshop; whilst remaining a successful publishing house, communal space and bookshop, was forced to close due to raising rent and a surge in ‘big-publisher’ reading material.

“It meant we had more time to do demonstrations.” Eric tells me.

In a way, everything that happens to him which seems bad, weather that is being incarcerated for a year, almost being kicked out from his home or being attacked by national front; it not only strengthened Eric Huntleys resolve, but his ability to revolutionise more minds in the process.

“The struggle never ends. There is always something to fight for.” He tells me with a muted smile on his face. Eric’s smile then dissipates and his follow up statement explains why. “It’s sad we have to continue fighting.”

It is clear that Eric Huntley has enjoyed his time spent challenging injustice. You get this from the way his formulates most of his answers because there is a slow, calculated pause between his answers, even after his lips twitch to give an indication that he has a first answer ready in wait.

“So who were your influences when you were growing up?” I ask him, hoping that there are even bigger powers in the anti-colonial debate to explore. Yet as he takes his moment to think, to pause and hold back an answer, his lip does not twitch. He stands still, looking up into the top right of his peripheral vision.

“There isn’t one really.” His answer is one I am forced to believe. Guyana, or British Guiana as it was then, was a notorious black spot in which international communication was very difficult to be accessed amongst the common people. Coupled with the fact Guyana was firmly under the thumb of the British Military, this meant that external and more radical influences were strictly controlled- if they were not in prison already.

“I read things by Marx and Lenin.” Eric tells me rather casually. It is said in a way in which the respect he holds for the ideologists is clear, yet their influence over his decisions and personal ideology has been minimal.

“So whom have you given the mantel over to then?” Is my final question. It is designed to once again discover a name who may be involved with the anti-colonial debate.

Yet the answer he delivers surprises me. “You!” He joyously exclaims. “The next generation. I am passing on the baton.”

And in my befuddlement, I realise I had no further questions.

No Colour Bar: Black British Work In Action 1960-1990 is currently in exhibition at the Guildhall Art Gallery till January 24th, 2016.