Scots proudly played their part in the abolition of the trade. But for a time we misted over our role as perpetrators of this barbarism. Many of Scotish industries, schools and churches were founded from the profits of African slavery.

Even Robert Burns was considering a position as a book-keeper in a plantation before poetry revived his fortunes. In 1796, Scots owned nearly 30 per cent of the estates in Jamaica and by 1817, a staggering 32 per cent of the slaves.

At any given time there were only about 70 or 80 slaves in Scotland but the country reaped the fruits of their labour in the colonies in the sugar, cotton and tobacco plantations.

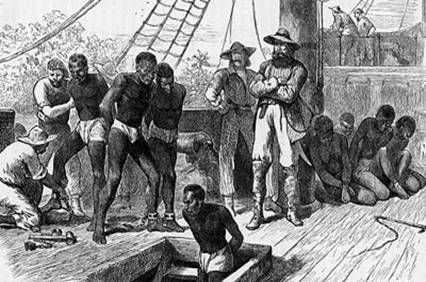

Many Scots masters were considered among the most brutal, with life expectancy on their plantations averaging a mere four years.

Iain Whyte, author of Scotland and the Abolition of Slavery, insists we have at times ignored our guilty past.

He said: “For many years Scotland’s historians harboured the illusion that our nation had little to do with the slave trade or plantation slavery.

“We swept it under the carpet. This was remarkable in the light of Glasgow’s wealth coming from tobacco, sugar and cotton, and Jamaica Streets being found in a number of Scottish towns and cities.

“It is healthy we are now recognising Scotland was very much involved.”

These industries, which saw Glasgow and much of the country flourish, were built on the back of slavery.

However, Scotland also punched above its weight in the abolition movement.

The MP for Hull, William Wilberforce, and his great influence, abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, are heralded as the heroes who outlawed slavery.

But Scots too played a huge role in winning the slaves their freedom. In 1792, the year that produced the most petitions for abolition, there were 561 from Britain – a third of which came from Scotland.

Mr Whyte said: “We can be ashamed of our past but also proud of it. There were many ordinary Scots who gave a lot of time, effort and sacrifice in the cause of seeking freedom.”

The owning of personal slaves was banned in Scotland in 1778-229 years before abolition of the trade.

This followed the case of James Knight, a slave who won his freedom when the Court of Session in Edinburgh ruled Scotland could not support slavery.

This important precedent didn’t mean all slaves were freed, but did mean no person in Scotland could beheld by law as a slave, which wasn’t the case in England.

Slave sales were banned in Scotland although at times Scots had profited from bringing slaves in to the country.

Mr Whyte said: “That was part of the deal to train up slaves and then sell them.”

One was brought from Virginia to Beith in Ayrshire and trained as joiner so he could be sold later for a profit. He ran away from Port Glasgow and died in Edinburgh’s Tollbooth Jail.

In 1807, the slave trade in British Colonies became illegal and British ships were no longer allowed to carry slaves.

However, complete abolition of slavery did not come until 1833. The Glasgow Anti-Slavery Society was formed in 1822 and the city was known as one of the staunchest abolitionist cities in Britain.

Wilberforce was heavily supported by Scots James Ramsay and Zachary Macaulay, who came from Inveraray.

Macaulay was repulsed by what he saw while working as an overseer in a West Indies plantation.

He founded the Anti-Slavery Reporter and eventually became governor of Sierra Leone, a colony founded by freed slaves.

The architect of the Abolition Bill was James Stephen, born of Scots parents and educated in Aberdeen.

But there is no doubt the profits slaves helped to create kick-started the industrial revolution in Scotland and brought it’s merchants and traders great wealth.

There were familiar names such as Scot Lyle of Tate and Lyle fame whose fortune was built on slavery. Ewing from Glasgow was the richest sugar producer in Jamaica.

The stunning Inveresk Lodge in Edinburgh, now open to the public, was bought by James Wedderburn with money earned from 27 years in Jamaica as a notorious slaver.

The Wee Free Church was founded using profits and donations from the slave trade. Even our schools have a dark history. Bathgate Academy was built from money willed by John Newland, a renowned slave master and Dollar Academy has a similar foundation.

For many years, the goods and profits from West Indian slavery were unloaded at Kingston docks in Glasgow.

Leith in Edinburgh and Glasgow were popular ports from which ambitious Scottish men sailed to make their fortunes as slave masters.

But Scotland was also home to slaves who were great instigators in winning their freedom. In his book, Mr Whyte chronicles the efforts of three black slaves who took their cases for emancipation to the Court of Session in Edinburgh.

One was Knight, another was David Spens, who in 1769 was baptised in Wemyss Church in Fife and claimed he should be freed since he was now a Christian.

Lawyers acted for him for free and his case became a cause celebre among ordinary miners and slaters in the area. Sadly, his master died before a legal judgement could be made.

Mr Whyte said: “There were slaves who struck out for freedom in Scotland and prepared the ground for abolition.”

Lord Auchinleck, a judge in the Knight case, said: “It may be the custom in Jamaica to make slaves of poor blacks but I do not believe it is agreeable to humanity nor to the Christian religion.

He is our brother, and he is a man.” The fact there were fewer black slaves in Scotland gave Scots a greater sense of their individuality. In one case in Glasgow in the 1760s, slave Ned Johnson was brought from Virginia and then saved by neighbours when he was hung up and whipped by his master in a barn.

Mr Whyte said: “The neighbours heard his cries, cut him down and took him to the magistrates to free him.

“These slaves were part of the community and that made it more difficult for people to hold on to slavery.

“There was a feeling in Scotland that something was wrong, which is not to say we didn’t let it go on for 300 years.”

But there was a deep-rooted fear in Britain that the wheels of commerce would grind to a halt without slavery.

It was only when economists like the Scot Adam Smith suggested slavery hampered freedom of enterprise that the argument took hold that it was no longer financially viable.

However, Mr Whyte argues: “It was about economics, but in many ways, like the dismantling of apartheid in South Africa, it was also about ordinary people standing up to be counted.”

By Annie Brown